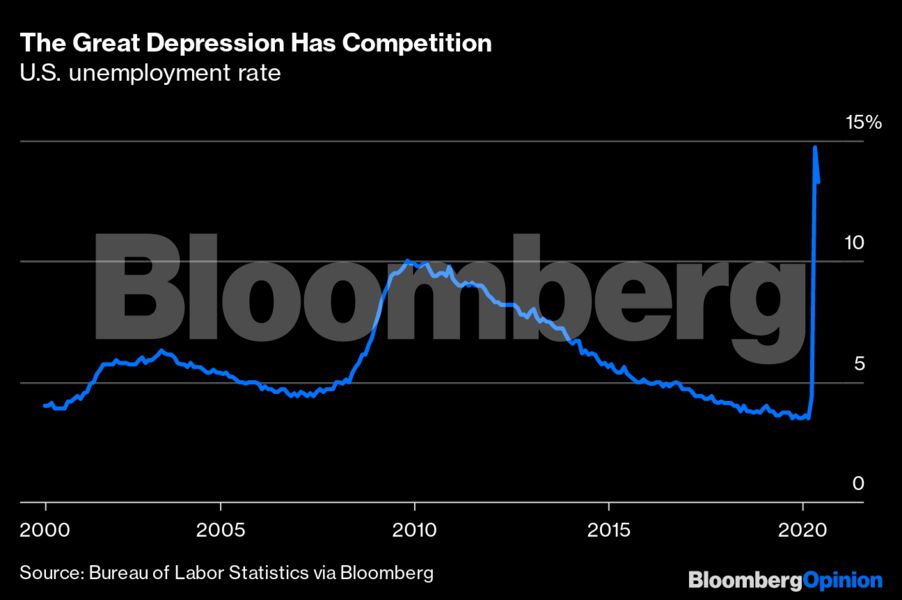

The National Bureau of Economic Research on Monday confirmed what everyone already knew: The U.S. is in a recession. But there is some good news too: the employment situation improved a bit in May, with the unemployment rate falling to 13.3%, from 14.7% in April.

There’s a bit of controversy about the true unemployment level -- counting workers who are still getting paid but not actually showing up for work, the unemployment rate was actually 19.7% in April and 16.3% in May. Many of those workers are probably on temporary paid leave during the pandemic; this is just what the Paycheck Protection Program was designed to encourage. But this ambiguity doesn’t matter very much because counting these temporarily idled workers as unemployed substantially increases the size of the May improvement.

This rapid switch from economic deterioration to recovery -- even as Covid-19 cases continue to pile up -- has raised spirits across the country. In the last recession, employment continued to deteriorate for more than a year after the 2008 collapse of Lehman Brothers; now, things seem to be on the upswing only a few months after the virus hit. There’s at least the glimmer of hope that the coronavirus recession will turn out to be like the Spanish Flu of a century before -- a ferocious onslaught followed by a quick rebound. Top macroeconomists such as Ben Bernanke and Paul Krugman have suggested that a rapid V-shaped recovery is a possibility.

But optimists should be cautious; May’s uptick might be just a dead-cat bounce. State reopenings are restoring some jobs, but fear of the virus will likely persist until treatments or a vaccine are available. That means reopenings will only partially restore business activity.

Job gains may slow down when workers on temporarily leave all return; those who worked for businesses that have now gone bankrupt will not be able to get their old jobs back. Jed Kolko, an economist at job search site Indeed, estimates that permanent unemployment is still rising. This is particularly troubling because people who are out of work for a long time can lose their skills, connections and work ethic, making it harder for them to find new jobs later.

So the economy may experience a V-shaped bounce, but it could be an incomplete one; unemployment might fall more but still remain unacceptably high, then begin a slow descent more characteristic of a U-shaped recession.

The question is how long that recovery will take. The typical culprit in slow recoveries -- a financial crisis -- seems unlikely to happen, thanks to swift and decisive action by the Federal Reserve. But there are other factors that might prolong the economic pain over several years.

One of these factors is human psychology -- what economists call animal spirits. The unprecedented speed and depth of the economic devastation from coronavirus might create pessimism among American businesspeople, consumers and investors that lingers for years. Irrational fear of pandemics might long outlast this particular disease simply because coronavirus looms so large in recent experience.