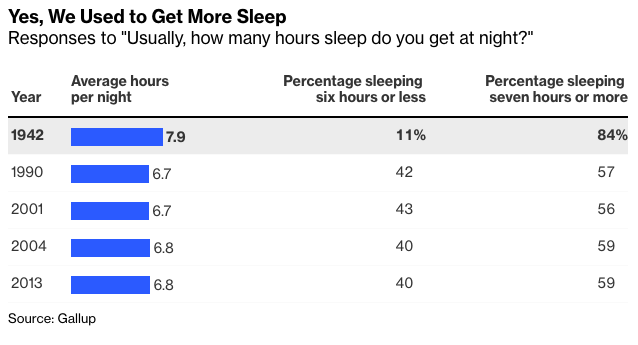

One thing that can be said with some confidence is that we are getting less sleep than in the age before the electric light — what is sometimes called “Edison’s anti-sleep revolution.” Quantitative evidence of this is limited, but Gallup does happen to have asked Americans about their sleeping habits in 1942, when home televisions were rare and many rural areas still didn’t have electricity, and average hours slept was about an hour longer than in recent polls.

The flattish trend in Gallup’s results since 1990 seems compatible with the ATUS results, given that they both show a modest increase in average sleep duration, but the average hours slept reported by Gallup is much lower than the ATUS average. That’s partly because Gallup’s accounting excludes daytime naps and “spells of sleeplessness,” but it may also be that asking people how much they usually sleep inevitably delivers different and presumably less-reliable results than collecting detailed 24-hour time diaries of the previous day, which is what the ATUS survey-takers do. Two recent studies that compared people’s self-assessments of how long they usually sleep with measurements (by actigraph) of how long they actually slept found that the self-assessments tend to err in the opposite direction from the one indicated by the Gallup/ATUS disagreement, though. That is, people overestimate how many hours they usually sleep, with the errors biggest for the shortest sleepers.

Where does that leave us? Well, a 2016 review of every study from 1960 through 2013 that used “objective” methods (either actigraphy or polysomnography) to measure sleep found no trend one way or another in sleep duration. A 2010 review that focused on U.S. time use surveys from 1975 through 2006, including the first four editions of the ATUS, found that average sleeping time was about the same in 2006 as in 1975, but was almost half an hour longer than in studies conducted in 1985 and 1998-1999. The latter review also found that the odds of being a “short sleeper” — that is, getting six or fewer hours of sleep a night — had risen significantly for full-time workers, although not for the population as a whole.

Two more recent studies based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Health Interview Survey, which asks respondents how many hours they usually sleep, have also found increases in the percentage of short sleepers over the past decade. One that focused on working adults found that the percentage getting less than seven hours of sleep a night rose from 30.9% in 2010 to 35.6% in 2018, with the prevalence highest among protective-service and military (50%) and healthcare-support occupations (45%). Another found a similar, if somewhat smaller, increase in short sleep among all adults, and that Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to report six or fewer hours of sleep than non-Hispanic Whites.

One possible reading of this is that sleep inequality may be rising even as average sleep duration is. Protective-service and health-care support workers often have little control over their schedules, which in turn often don’t fit their circadian rhythms. Home environment is also an issue, with nearly 11% of Hispanic households and 3.6% of Black households having more than one occupant per room, compared with just 1.4% of non-Hispanic White ones. The financial distress and instability that accompanied and followed the Great Recession may have made sleep harder for many as well.

For Americans in more comfortable situations and in more control of their schedules, on the other hand, the messaging from the media and the medical establishment about the importance of sleep may actually be having an effect. One 2018 study of ATUS data found that the sleep increase since 2003 had been accompanied by a decrease in time spent reading and watching TV or movies (on any kind of device) just before going to sleep. The authors, University of Pennsylvania psychiatry professors Matthias Basner and David F. Dinges, concluded that:

This can be interpreted as a sign of increasing willingness in parts of the population to relinquish these popular prebed activities to obtain more sleep and may in part be attributed to educational campaigns, scientific reports of the health risks of reduced sleep duration, and the increasing interest in sleep loss and its consequences in both the scientific and the popular literature.

See, people do pay attention to the health advice they hear and read! It may just be that, in the case of sleep, not everyone is in position to act on it.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of The Myth of the Rational Market.