Likewise, the Bank for International Settlements’ Aging and Asset Prices paper predicts that as older investors sell their homes and financial assets to fund their retirement years, and there are fewer younger workers to take their place, asset prices will face a much tougher environment.

A convincing counterargument is made by fixed income giant PIMCO. PIMCO cares profoundly about the direction of interest rates and bond yields, and it doubts the global savings glut is going to end any time soon—arguing that aging demographics in the United States will provide a tailwind for bonds and keep interest rates low for at least another decade.

The reason? The better off you are, the more likely you are to work longer and save more. In 1998, of the top 20 percent of U.S. earners aged 65-74, two out of five were in the labor force; now three out of five are still working. The percentage of working 75-year-olds has more than doubled. PIMCO finds that U.S. households accounting for the vast majority of personal income do not reduce their savings until their 70s, and they will drive continued demand for fixed income assets. The conclusion: “Combine a low global neutral interest rate and strong domestic demand for bonds, and what do you get? Lower rates for longer in the U.S.”

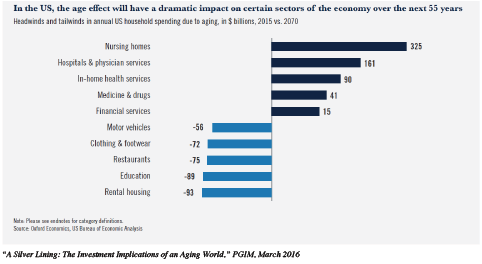

Prudential’s investment unit PGIM is also skeptical of an asset “meltdown” caused by boomers drawing down their savings, noting there is no strong empirical support for a correlation between asset prices and age structure. Its report, "A Silver Lining: The Investment Implications of an Aging World," is a must-read for the bull scenario.

PGIM’s analysis of long-range consumer trends is striking. Spending by older consumers on senior care, health and financial services could increase by hundreds of billions of dollars per year, while cars, apparel and even education, face long-term headwinds.

Chart 2: Headwinds And Tailwinds In Annual U.S. Household Spending Due To Aging