The banking industry is one of the foundational pieces of any economy. But some might argue it’s also one of the most hated and, from an investment standpoint, one of the most misunderstood. Take the sector’s recent low stock market valuation, for example.

Fund manager Chris Davis believes that this sentiment is out of line given the solid fundamentals of the largest—and what he considers to be the best-run—businesses in banking. And he posits that a realignment between perception and reality will make these companies fruitful investments for his fund in the coming years.

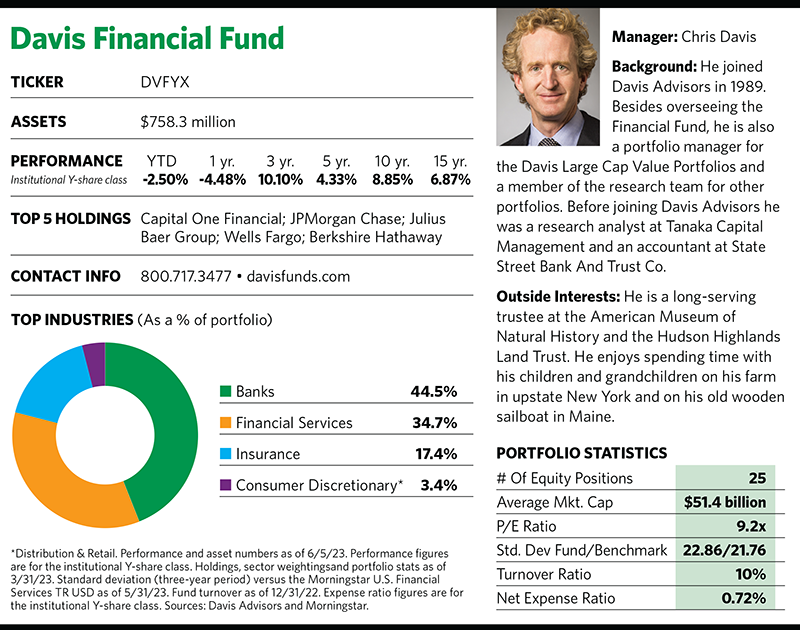

Davis, a co-portfolio manager of the Davis Financial Fund, joined the family business of Davis Advisors in 1989. His family has been engaged in the financial services space as far back as the 1940s, when his grandfather, Shelby Cullom Davis, started building what ultimately became an $800 million fortune by investing primarily in insurance stocks. In 1969 Chris Davis’s father, Shelby M.C. Davis, formed Davis Advisors and began managing his own mutual funds. From his two elders, Chris Davis learned the inner workings of the financial services business. (Chris also currently serves as an outside director of Berkshire Hathaway, along with its chairman, Warren Buffett.)

Today, Davis Advisors’ product mix comprises mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, variable annuities and separately managed accounts. Thirty-two years ago the firm launched the Financial Fund, which the company says had produced an average annual return of 10.62% from inception through this year’s first quarter—at the same time the Lipper financial services category average return was 10.10%. The fund has also outperformed the S&P 500 and S&P 500 financials indexes during that period, the firm says.

Chris Davis, who helped manage the Financial Fund earlier in his career before stepping away to focus on other areas at the firm, returned to the helm nine years ago. He has seen the ebbs and flows of the financial services industry through the years, so he more or less took it in stride when the regional bank crisis unfolded in March.

For starters, regional banks weren’t part of his fund’s large-cap portfolio. Second, he and fund co-portfolio manager Pierce Crosbie had already anticipated the trouble: They had flagged the interest rate risks being taken by certain banks and they had called out First Republic by name before it turned out to be one of three recent high-profile failures.

Not Feeling The Love

While the Davis Financial Fund includes insurance and other financial services firms in its portfolio, banks represented the fund’s largest industry weight at nearly 45% as of this year’s first quarter. In recent years, Davis and Crosbie had noted in their newsletters how historically low interest rates had suppressed bank earnings by squeezing the spreads banks could earn on customer deposits, and said that the inevitable rise in interest rates would act like a coiled spring to unleash greater earnings potential. That came to fruition over the past year as the Federal Reserve increased the fed funds rate by 500 basis points from March 2002 through May 2023.

But Davis says some banks benefited more from this than others depending on how management had positioned their companies. In particular, he notes, the likes of JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo saw dramatic increases in interest income while simultaneously minimizing their balance sheet risk as rates increased.

“We’ve seen companies that took irresponsible interest rate risk pay the price. We’ve seen deposits flow out of those institutions and into institutions that are safer, larger, have better accounting standards, more capital and took less interest rate risk. So money is flowing into the Wells Fargos and JPMorgans,” he says.

But investors have seemingly yawned and haven’t taken much notice. “We thought the stocks of the banks that are well managed and well positioned would be benefiting from this, not just relative to the other banks but relative to the market as a whole,” Davis says. “And that hasn’t been happening.”

Indeed, the Financial Fund was down 2.5% this year through June 5 while the S&P 500 gained 11.3%. Davis adds that he thought the Covid-fueled recession would begin the upward re-rating of the largest, best-of-breed banks because they proved their strength by providing liquidity that helped the economy rebound quickly.

“But because that recession was very short-lived there wasn’t a sense of how resilient the banks have become,” Davis explains. “And as we head into a [possible] downturn the banks are incredibly well-positioned except for those mismanaged banks that took catastrophic interest-rate risk.”

He believes some investors remain wary of banks because of their role in creating the financial crisis of 2008-2009. “In the meantime the capital and earnings are piling up in these [well-run bank] businesses,” Davis says. “There’s no fundamental reason for these stocks to be down; they’re down due to psychology.”

Recession Concerns

Some investors are spooked by banks because they fear a possible recession following the Fed’s aggressive interest rate hikes. For Davis, that presents opportunities in select banking names. His confidence in those names is summed up in two words: “stress test.” In other words, they’ve had to run with strict guardrails in place since the financial crisis.

“When we went into Covid they moved the goalposts and made it even more severe, and the banks still passed,” he says.

Nonetheless, even if the U.S. avoids a recession some investors are concerned about a potential crisis in the wobbly commercial real estate market. Davis counters that he and Crosbie are comfortable with the credit risk of the loans held by the major banks in the fund’s portfolio.

“There is strong evidence to believe that the credit risk in the major banks that we own is completely manageable and is anticipated, and that a disproportionate amount of credit risk is dispersed in other parts of both the banking and financial sector—partly in smaller banks with a disproportionate share of commercial real estate, and partly in things like credit funds and pension funds and life insurance companies where I think there will be significant losses,” he says.

Beyond that, though, he’s worried about heightened regulation in the wake of the recent regional bank failures and believes there could be political hay to make by lawmakers bashing banks in general—even those institutions with their houses in order. “What I hear in the media is, ‘Why are we bailing out banks again?’” Davis says. “There’s a general anger [toward banks] that’s totally unfair and irrational. But that doesn’t mean there won’t be consequences to it. I can imagine a putative regulatory environment even to those companies that behaved very well in this environment.”

Art Of The Specific

Davis likes to say that investing is the art of the specific, and he believes that’s especially true in financial services where there can be a significant dispersion of returns over time among the different players. That’s why he focuses on those larger banks he thinks have durable competitive advantages derived from their level of technology spending, coupled with their financial heft to better handle compliance costs. He posits that these bellwether banks also enjoy better diversified asset and funding bases, higher capital ratios, and better accounting standards.

“Those fundamentals, combined with banks trading at the largest discount we’ve ever seen relative to the S&P 500, is what specifically draws us to banking,” he says.

The Financial Fund is sprinkled with what Davis calls “national champion banks” in stable countries where he and Crosbie are comfortable investing in the currency and in the local economy. “Many of these banks have yields above 5% and capital ratios that are among the highest in the world,” Davis says.

He points specifically to Singapore’s DBS Group Holdings, Denmark’s Danske Bank and Norway’s DNB Bank. “And we own Swiss bank Julius Baer. These are good holdings to have when we think of generational wealth building in a financial services fund,” he says.

The fund’s recent top holding was Capital One Financial Group, which Davis calls the most successful fintech company ever. “Nobody describes it that way, but Capital One was founded to use data science to disrupt one of the most lucrative aspects of financial services, which was credit cards,” he says. “They had no branches or brand name. They just used a bunch of data science to target offers to individual customers in an industry where it had been one size fits all.”

Davis believes banks have suffered an unfair bad reputation through the decades. While he says he’s not an apologist for the industry, he is a big believer in the large, well-funded banks that make it into his fund’s portfolio and suggests that these types of companies are poised to survive whatever potential economic downturn comes our way and that investors will eventually reward them with higher multiples.