In “Shuggie Bain,” Douglas Stuart’s award-winning and harrowing depiction of alcoholism, sectarianism and deprivation in post-industrial Scotland, money is always scarce and often dirty. Deserted by her second husband and unable to hold down a job, Shuggie’s mother, Agnes, relies on her twice-a-week child benefit to feed her children — or her booze habit. As the latter nearly always wins, she and Shuggie are regularly reduced to desperate expedients to fend off starvation: Extracting coins from electricity and television meters, pawning their few valuable possessions, and ultimately selling their bodies for brutal sexual favors.

Stuart vividly captures the miseries of a Glasgow of greasy coins and filthy banknotes. After one of many wretched copulations in the back of a taxi, one of Agnes’s lovers inadvertently showers her with coins from his pocket. Shuggie’s father briefly reappears at one point, handing his son two 20-pence pieces from his taxi’s change dispenser by way of a gift, grudgingly adding four 50-pence pieces when the boy looks nonplused. (“Don’t ask for mair!”) The “rag-and-bone man,” who goes from house to house buying old clothes and junk, pays “with a roll of grubby pound notes” bound by an old Band-Aid. The image is especially startling because banknotes have so rarely featured in the narrative. The only credit in this world is from rent-to-own catalogues, the Provident doorstep lender, and a few hard-pressed shopkeepers.

I grew up in middle-class, mostly sober Glasgow, but I still remember the tyranny of those damned coins: the nightmare of having too few for a bus fare or the wrong sort for a phone box. To my children, all this is as much a part of ancient lore as pirate chests of doubloons once were to me. Coins are fast fading from their lives, soon to be followed by banknotes. In some parts of the world — not only China but also Sweden — nearly all payments are now electronic. In the U.S., debit card transactions have exceeded cash transactions since 2017. Even in Latin America and parts of Africa, cash is yielding to cards and a growing number of people manage their money through their phones.

We are living through a monetary revolution so multifaceted that few of us comprehend its full extent. The technological transformation of the Internet is driving this revolution. The pandemic of 2020 has accelerated it. To illustrate the extent of our confusion, consider the divergent performance of three forms of money this year: the U.S. dollar, gold and Bitcoin.

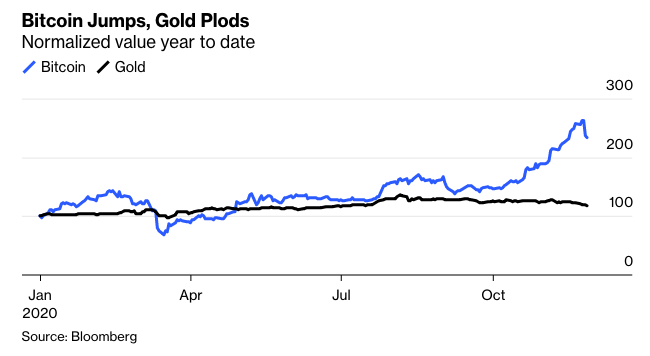

The dollar is the world’s favorite money, not only dominant in central bank reserves but in international transactions. It is a fiat currency, its supply determined by the Federal Reserve and U.S. banks. We can compute its value relative to the goods consumers buy, according to which measure it has scarcely depreciated this year (inflation is running at 1.2%), or relative to other fiat currencies. On the latter basis, according to Bloomberg’s dollar spot index, it is down 4% since Jan. 1. Gold, by contrast, is up 15% in dollar terms. But the dollar price of a bitcoin has risen 139% year-to-date.

This year’s Bitcoin rally has caught many smart people by surprise. Last week’s high was just below the peak of the last rally ($19,892 according to the exchange Coinbase) in December 2017. When Bitcoin subsequently sold off, the New York University economist Nouriel Roubini didn’t hold back. Bitcoin, he told CNBC in February 2018, had been the “biggest bubble in human history.” Its price would now “crash to zero.” Eight months later, Roubini returned to the fray in congressional testimony, denouncing Bitcoin as the “mother of all scams.” In tweets, he referred to it as “Shitcoin.”

Fast forward to November 2020, and Roubini has been forced to change his tune. Bitcoin, he conceded in an interview with Yahoo Finance, was “maybe a partial store of value, because … it cannot be so easily debased because there is at least an algorithm that decides how much the supply of bitcoin raises over time.” If I were as fond of hyperbole as he is, I would call this the biggest conversion since St. Paul.

Roubini is not the only one who has been forced to reassess Bitcoin this year. Among the big-name investors who have turned bullish are Paul Tudor Jones, Stan Druckenmiller and Bill Miller. Even Ray Dalio admitted the other day that he “might be missing something” about Bitcoin.

Financial journalists, too, are capitulating: On Tuesday, the Financial Times’s Izabella Kaminska, a long-time cryptocurrency skeptic, conceded that Bitcoin had a valid use-case as a hedge against a dystopian future “in which the world slips towards authoritarianism and civil liberties cannot be taken for granted.” She is on to something there, as we shall see.