A sense of crisis is creeping into fixed-income markets at the start of the fourth quarter, coming off the back of a rocky September. The queue of soothsayers warning of impending doom is lengthening; growing concern about U.S. domestic politics as well as the global economic backdrop risks sparking a full-blown market rout.

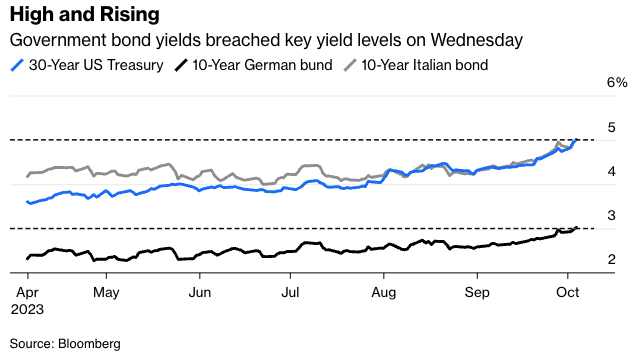

Until the Federal Reserve finally calls time on its 18-month rate-hiking cycle, the bond-market beatings will continue. Something serious may break in the meantime as the sound of rivets popping around the world is getting louder. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield has risen almost 150 basis points since May, reaching 4.8%. The 30-year bond breached 5% on Wednesday, as did the 10-year Italian bond. Europe’s benchmark security, the 10-year German bund, surpassed 3%. It's looking like a slow-motion train wreck, with worrying echoes of the October 1987 Wall Street crash.

Unfortunately, Fed officials have intimated this week that another interest-rate hike is potentially on the table for the Nov. 1 meeting. Furthermore, this week's economic data is showing ever more resilience. The August U.S. manufacturing ISM survey turned upwards to 49 from 47.6, while the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, showed Tuesday that the number of available positions rose to 9.61 million in August from a revised 8.92 million in July.

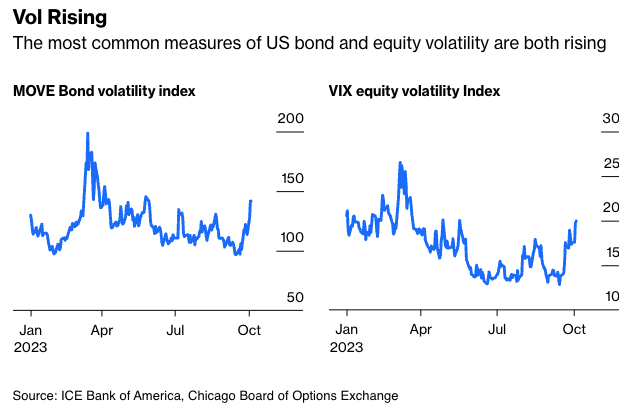

It's the last thing bond traders banking on U.S. official interest rates being at their peak needed. Volatility measures are rising across equity and bond markets. Friday's nonfarm payrolls report will be a key test of how strong the U.S. labor market really is, and how the Fed will respond.

The list of known risk factors for fixed income is expanding, and that's before any unknown unknowns crop up. President Joe Biden’s administration is still splurging on fiscal stimulus, with a concomitant greater need to borrow as the $32 trillion U.S. national debt climbs ever higher. The parlous state of U.S. politics just took another lurch with the ouster of U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. It makes the prospect of finding a longer-term solution to funding the government, with Congress needing to reach a spending agreement by mid-November or risk a shutdown, even less likely.

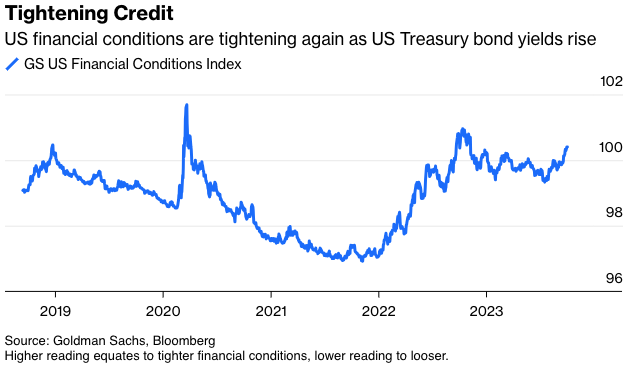

Higher oil prices, and extended production cuts, mean the battle to curb inflation remains very much alive. Sharply declining money-supply data across the developed world, in concert with falling bank lending, is tightening financial conditions. Covid-19 is also rearing its ugly head again just to add a biblical element to the mix.

Central to the problem of higher U.S. yields is waning demand from overseas. China's post-Covid economic recovery is struggling badly, and the need to counteract the weakness of the yuan to the dollar makes it even less likely to invest in U.S. assets. Similarly, the decline in the Japanese yen, which briefly exceeded 150 to the dollar on Tuesday, makes Treasury bonds an ever less appealing investment for its large investor base.

The bond vigilantes have seized control of global markets. Until either the economic data weakens significantly or a sudden crisis explodes, it’s solely up to the Fed to assess how far it lets the rise in U.S. bond yields go. Let's hope it knows more than the rest of us—otherwise it's time to get off the bond train before it crashes.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. Previously, he was chief markets strategist for Haitong Securities in London.