Last December, Florida’s legislature passed a controversial but necessary set of reforms aimed at shoring up the state’s teetering property insurance market, where a string of insurers had canceled policies and even filed for bankruptcy, leaving homeowners with dwindling options. This month, Farmers and AAA announced that they, too, were reducing exposure to the state, prompting some Florida watchers to speculate that the reform had failed. In reality, it’s too early to conclude that, and Berkshire Hathaway’s big new bet on Florida reinsurance is a sign that the outlook may be improving modestly.

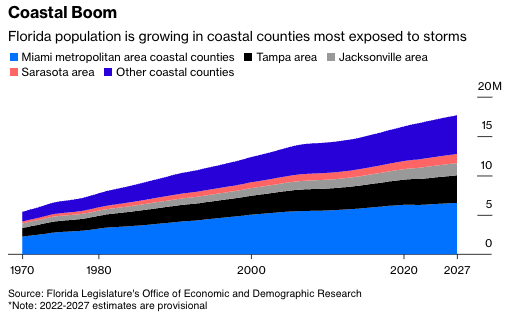

First, let’s review how we got here. Florida is home to a booming coastal population, rapidly appreciating property prices and soaring construction costs, all in a state that sits at the edge of Hurricane Alley and figures to be among the places hit hardest by rising sea levels. It’s also the top state for property insurance-related lawsuits, which companies contend are frequently frivolous and often fraudulent, pushing the cost of doing business even higher.

But a less appreciated facet of the crisis is the critical role of reinsurance—a form of “insurance for insurers” that kicks in when catastrophic damage exceeds a certain level. Florida is dominated by small and medium-sized insurers, which rely on reinsurance to keep their businesses viable, and the sharp drop in reinsurers’ risk appetite acted like an accelerant for the property insurance troubles. If primary insurers can’t get enough reinsurance, they have to reduce their exposure to the state, and for a variety of reasons, reinsurance firms retrenched in 2022.

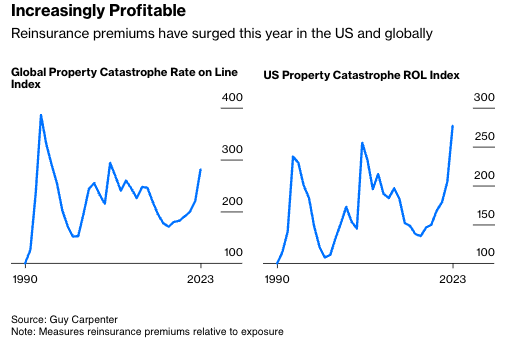

A streak of nationwide natural disasters, punctuated by Hurricane Ian in late September, left them licking their wounds, while the collapse of the fixed-income market left their balance sheets suddenly weaker. “The problem was, you couldn’t get [reinsurance] at any price,” said my colleague Matthew Palazola, senior insurance analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence. This year, by contrast, prices are way up, but at least it’s available to those able to pay. The Guy Carpenter U.S. Property Catastrophe Rate on Line Index—a measure of reinsurance pricing relative to exposure—recently surged to a record, with Florida renewals playing a role.

In remarks at Berkshire’s 2023 annual meeting, Vice Chairman of Insurance Operations Ajit Jain said the firm had boosted its property-catastrophe exposure by nearly 50% this year, including up to $15 billion now at risk in Florida. Here’s how Jain explained the decision at the time (emphasis mine):

We had a lot of powder dry and we were lucky that we kept the powder dry, because April 1 suddenly prices zoomed up again a lot higher than what they were on January 1, and starting to look attractive to us... Net-net, I’m very happy with the portfolio. It’s been a lot better—it is a lot better than what it’s been in the past. I don’t know how long it will last, and of course, if the hurricane happens in Florida, we could lose across all the units, we could lose as much as $15 billion. And if there isn’t a loss, we will make several billion dollars as profit.

Berkshire’s Warren Buffett, of course, is famous for saying—in his 1986 Berkshire letter to shareholders—that good investors ought to “attempt to be fearful when others are greedy and to be greedy only when others are fearful.” In that spirit, Berkshire’s reinsurance arm sounds as if it saw a unique opportunity to profit from Florida’s much-hated market, and a few industry peers seem to be on the same page. Here’s Kevin O’Donnell, chief executive officer of RenaissanceRe Holdings Ltd., another reinsurer that does business in Florida (from RenRe’s first-quarter earnings call, again emphasis mine):

Florida, in particular, was coming off a reasonably good rate adequacy level and we’re getting significantly more rates. So, I feel that that’s going to be an attractive market for us. And I don’t see any pressure that’s going to have a step change bringing us back down to where we traded before.

In the Florida insurance ecosystem, the reinsurers are the canary in the coal mine, and hints of their resurgent risk appetite probably mean that the acute phase of the crisis is ending (for now.) News like the developments at Farmers and AAA will continue in dribs and drabs but generally reflect the lagged fallout from last year’s developments. What emerges from the above remarks is a picture of companies that are increasingly willing to bear Florida risk for the right price.

In the long run, however, homeowners and policymakers are likely to find there are no silver bullets. The simple fact is that Florida property risk is high and rising, which means that reinsurance costs will remain commensurately elevated. As sea levels rise and disasters become increasingly frequent, coastal living will remain accessible only to those with the deepest pockets; the rest are on borrowed time.

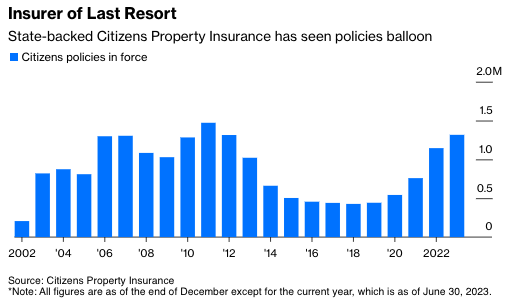

Notably, the state has pursued a number of interventions since Hurricane Andrew—the devastating 1992 storm that first upended the insurance market—to forestall the inevitable transmission of higher rates. That has included the establishment of a state-backed insurer of last resort for homeowners who can’t obtain coverage elsewhere and the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, which is essentially a state-backed reinsurer that provides relatively inexpensive coverage up to certain levels. Neither of these is a sustainable long-term fix. State-backed entities that undercut the private sector tend to crowd out private players. Eventually, the state is left holding the bag for an ever-growing amount of catastrophe exposure, which is why the recent reform took steps to limit the alarming growth of the insurer of last resort, Citizens Property Insurance Corp. (Florida homeowners can get a Citizens policy at an implicitly subsidized rate if private premiums are at least 20% more expensive, and once they arrive, they often stay with the state-backed insurer. Private players complain that the arrangement puts an artificial cap on the market. The new legislation forces homeowners to leave Citizens once they can again find private-sector policies within the 20% price rule. In theory, that turns Citizens into a pit stop instead of a permanent landing spot for homeowners.) One way or another, the costs trickle down to homeowners, whether it’s through pricier private insurance premiums or, alternatively, new taxes.

As to the recent reforms, time will tell whether they can help mitigate the higher costs to some degree. Among other things, the package sought to curb the nuisance litigation by ending the so-called one-way attorney fee statute. Until the change, insurers had to pay prevailing plaintiffs’ attorney fees, an arrangement that the industry says incentivized frivolous lawsuits and helped build a cottage industry around exploitation of the system. In the most egregious cases, contractors would goad homeowners into filing claims under false pretenses, and insurers were often forced to settle to protect against soaring legal fees. Reinsurers in particular are “optimistic that between [higher prices] and the litigation reforms that Florida is becoming more attractive,” Frank Nutter, president of the Reinsurance Association of America, told me by phone on Tuesday. On the flip side, however, the many honest homeowners seeking fair payments for devastating storm damages will now have a more uneven playing field against insurers’ legal teams.

If the reform works as intended, insurance companies’ legal costs should drop, improving their business prospects. But that won’t be put to the test until, inevitably, the next storm hits Florida, so it’s wildly premature to render a verdict. In the meantime, Berkshire’s big bet on Florida is an early sign that at least the market hasn’t abandoned the state. In fact, the industry will gladly stick around for the long haul, but only at the “right price”—and that in and of itself will be a hard pill to swallow for the average homeowner.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg News journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he served as the company's Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.