The word “infrastructure” denotes bigness—big projects, big costs and big investment opportunities. That’s why investors get excited when something like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law comes down the pike. This legislation from 2021 aims to modernize various segments of America’s aging physical infrastructure while expanding its digital infrastructure.

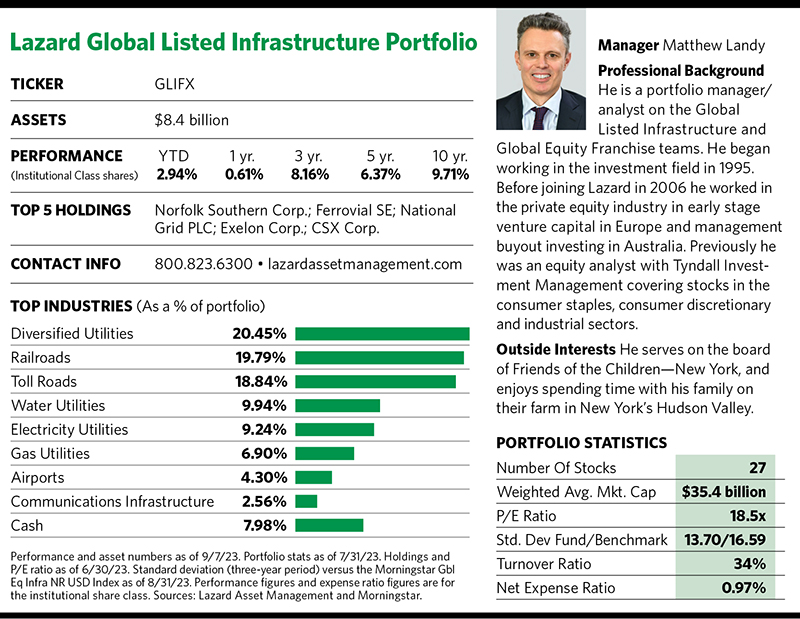

That type of news often triggers inflows into infrastructure funds, but the people running one of the top funds in that category over the past 10 years believe that not all infrastructure is created equal. “The very best infrastructure assets have wonderful investment characteristics,” says Matthew Landy, one of four portfolio managers at the Lazard Global Listed Infrastructure Portfolio. Lazard calls these “preferred infrastructure” companies.

He posits that the best opportunities are assets that last for decades, such as toll roads, airports and the electricity grids that underpin the functioning of developed economies. “They last a long time, as do the cash flows attached to them.”

He and his team also focus on assets with low risk of capital loss, since these are often regulated monopolies providing essential services. “So as long as you don’t overpay or overleverage the assets, your risk of permanent capital loss is relatively low.”

Ideal infrastructure investments also enjoy defenses against inflation: Because they’re typically regulated, they’re allowed to raise service costs and pass through higher expenses to customers. Landy says this gives the assets a diversification benefit, since the cash flows tend to be stable and are less correlated to economic activity than many other types of equities.

“As a package we think all of that is compelling,” he says. “But in listed markets there are many things that are labeled as infrastructure that we think are much riskier than the characteristics I just described.”

More specifically, he points to the roughly 400 securities globally in the listed market that are identified as infrastructure, yet he and his team believe that less than 90 meet Lazard’s “preferred” definition. “To access the benefits of infrastructure we think you need to be very selective up front about what you even consider investing in,” Landy says.

Their strategy has made the Global Listed Infrastructure Portfolio’s institutional share class product the top performing fund in Morningstar’s infrastructure category when the returns are annualized over the past 10 years. It has also landed among the category’s top 10 funds during the one-, three- and five-year periods.

CPI + 5%

The fund’s long-running investment objective is to achieve an investment return of inflation plus 5%. To achieve their objective the fund’s managers avoid certain areas that often play prominent roles in indexes or in competing funds. For example, the Global Listed Infrastructure Portfolio excludes unregulated electricity generators because the field has too much competition.

“And our universe doesn’t include companies that build infrastructure assets because they don’t have the monopolistic and predictability characteristics that we look for,” Landy says. “We want to own the infrastructure monopoly itself.”

The fund also excludes midstream pipeline companies, which Landy says surprises some investors. “Midstream companies have lower barriers to entry than interstate pipelines,” he says. “And there’s also a degree of commodity exposure, which we don’t like in our portfolio because we don’t think people want that in a low-risk infrastructure portfolio.”

Morningstar analyst Tim Wong noted in a recent report that “Lazard remains among the more narrowly defined strategies in the cohort,” resulting in the fund avoiding sectors such as data centers that have potential for faster earnings growth.

“Data centers don’t fit because we see them as real estate assets rather than infrastructure assets,” Landy says. Nor do data centers enjoy a monopoly, he adds.

Finally, the fund steers clear of emerging markets because they want to invest in assets based in countries with proven economic and legal systems. “To be clear, political and regulatory risks exist in developed markets as well,” Landy points out. “But the difference in developed economies is that they have an independent judicial system that’s free from political interference. In some emerging markets it’s not clear that there’s an independent judicial system.”

Expensive North America

At the end of July, the portfolio held 27 positions while its benchmark, the MSCI World Core Infrastructure (U.S. dollar-hedged) Index had 105 holdings. The fund’s sector allocation leaned heaviest on diversified utilities (which made up 20.5% of the fund), railroads (19.8%) and toll roads (18.8%). And while the U.S. was the largest country weighting at nearly 28%, that was far less than the benchmark’s 57% weighting to the U.S.

The portfolio’s lean composition reflects the fact that equity prices have appreciated significantly. That means fewer names are attractive, something pointed out by Morningstar’s Wong when he said the fund’s portfolio ranges from 25 to 50 stocks and gravitates toward the lower end when the managers think that equities are pricey.

“We think the stock market in general looks expensive, and that’s spilled over to the infrastructure space as well—particularly for sectors that have benefited from the very long period of low interest rates,” Landy says. “A classic example is the U.S. utility sector and North American infrastructure in general. The exception is U.S. railroads, where we see some value, along with a couple of regulated U.S. utilities. We’re currently very underweight North America now, which typically would represent 55% to 70% of the exposure.”

On the flip side, Landy sees opportunities in Europe and the U.K., where he says utilities and certain other assets are favorably priced. “Toll road companies in Europe are very attractive,” he notes. “Being selective is really important and it’s very much about stock picking.”

Tri-Continental

Lazard’s five-member team working on global listed infrastructure includes Landy and three co-portfolio managers—John Mulquiney and Warryn Robertson are based in Sydney, Australia, and Bertrand Cliquet works in London. Landy is a Melbourne, Australia native who’s been based in New York City for 17 years.

Along with Sydney-based research analyst Anthony Rohrlach, they hold weekly investment calls for one to three hours where they discuss all of the analysis produced by the team during the prior week. “We’re all analysts who have stock coverage,” Landy says. “We all have our valuation models, write research reports, read 10-Ks, and speak to management teams.”

The objective is to come up with an agreed-upon intrinsic value for the securities being discussed. Landy notes that the calls can be heated and animated, but it’s a very important process where they peer review one another’s work so that everyone understands the others’ companies very well and can agree on each stock’s intrinsic value.

From there a stock is ranked according to its expected return, and the managers use that ranking—in combination with liquidity and risk management considerations—to construct the portfolio.

The fund recently sported a sizable dividend of about 4%. “Most of the assets we invest in are monopolistic and fairly mature cash-generating businesses,” Landy says. “They have higher dividend payout ratios than most sectors. But we don’t target dividend yields; it’s just part of the return equation.”

The Global Listed Infrastructure Portfolio began as a strategy for institutional clients; it launched as a mutual fund in late 2009. Landy says some investors see it as a defensive global equity portfolio while others include it in their real asset exposure or as part of a specific infrastructure allocation. Some investors use it to complement their private equity infrastructure exposure, while others use it as an inflation hedge given the sector’s ability to pass through higher prices.

“The strategy has been a good diversifier historically,” Landy says. “Apart from the absolute return stream, the beta of the fund has been about 0.6 compared to global equities over the past decade with low volatility.” (Beta measures a security’s or portfolio’s volatility versus the overall equity market, which has a beta of 1. An investment with a beta below 1 is less volatile than the market.)

Despite the fund’s solid long-term track record, it stumbled in 2020 when it underperformed both its category and its benchmark by roughly four percentage points. A primary reason is that the portfolio was skewed to assets that were particularly vulnerable to the pandemic-fueled global shutdown.

“We had a lot of exposure to what we call patronage-risk assets such as toll roads and airports where there’s a degree of volume risk. Pandemic lockdowns restricted use in those assets,” Landy says, adding that 2020 was disappointing because the fund’s broadly defensive characteristics typically do well in down markets.

“In 2022 we defended very well when the stock market fell a lot,” he notes. The fund’s institutional share class fell 1.3% last year, which was six to seven percentage points better than the numbers scored by both its category and benchmark. “We lost a little bit of money, but certainly not as much as people lost in the overall equity market or even in their bond portfolio. So we were quietly pleased in that sense.”

He says that during the pandemic the management team redid all of its forecasts and assumed there would be a very deep and prolonged recession with volumes on most assets not getting back to pre-pandemic levels until 2024-2025.

“After we went through that exercise we felt the stocks that we owned still looked attractive,” he says. “As a result, the portfolio didn’t change that much. And of course, volumes on most assets have come back and the share prices have performed well since then.”