A credit default swap (CDS) is designed to transfer the credit exposure of fixed income products between parties. The buyer of a credit swap receives credit protection, whereas the seller of the swap guarantees the credit worthiness of the product. By doing this, the risk of default is transferred from the holder of the fixed income security to the seller of the swap.

Authoritative Concern

China watchers were struck recently when an article published in the Chinese People’s Daily, the official news outlet for the Communist Party (and therefore, the Chinese government), condemned the country’s reliance on leverage. Debt was referred to it as an “original sin” that leads to subsequent risks. The article also called on the government to stop resorting to additional debt-fueled stimulus to prop up failing industries and zombie SOEs. The interviewee was identified only as “an authoritative person” believed to be either President Xi Jinping or one of his most senior advisors. That an article so openly critical of government policy was published in an official news outlet shows that the level of concern in China is high and reaches the top levels in government.

China Cracked but not shattered

China’s debt problems are bad, but not insurmountable, for several reasons. First, most of the debt is owed internally. Furthermore, to the extent that the government is often a partner, officially or not, with the lenders (mostly banks) and debtors (mostly SOEs), the Chinese asset/liability equation is closer to balance than many people understand. In many instances, though not all, the Chinese government owes money to itself. When countries typically have debt problems, it’s because they have external creditors that cannot be satisfied. Recently this has been the situation with Greece and Argentina. Greece had external debt equal to over 75% of its GDP. That figure for China is under 10%.[1]

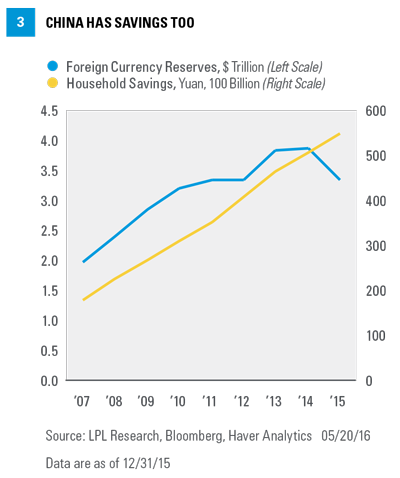

The other bit of positive news from China can be seen in Figure 3. We see the steady growth in household banking deposits in China. The Chinese people save a lot, approximately 30% of their income, compared to roughly 5% savings rate for the U.S. As their income has grown, so have their savings in absolute terms. This provides the ability for Chinese companies and government entities to finance their expansion without having to look overseas. But China’s high savings rate has proven to be as problematic as it appears virtuous. By most accounts, the Chinese save too much and spend too little, undermining the government’s attempts to rebalance the economy away from investment and toward consumption.

The other item displayed in Figure 3 is Chinese foreign currency reserves, which declined last year as the government sought to stabilize both the economy and the value of the yuan. But even so, with over $3 trillion in total reserves, including approximately $2 trillion in U.S. Treasury bonds, China has a massive war chest that can be used to at least pay off its foreign creditors if need be.

How bad are the cracks in China?