A friend of mine who is a bit of a climate-change skeptic once challenged me with this question: If climate change is such a pressing danger, why haven’t coastal real estate prices crashed?

It’s a fair question. If financial markets are even close to efficient, and if everyone knows climate change is about to flood the coasts, then it stands to reason that buyers would be shunning any real estate in the path of rising sea levels. Prices should retreat, at least somewhere.

Now, one quick and easy rebuttal is that housing markets aren’t very efficient (remember 2008?). Since it’s very difficult to short-sell coastal real estate, the price should be set not by the average investor, but by the most optimistic. And all it would take would be a few investors who didn’t believe in climate change—or at least, who haven’t started thinking seriously about its implications—to keep prices well above their rational level.

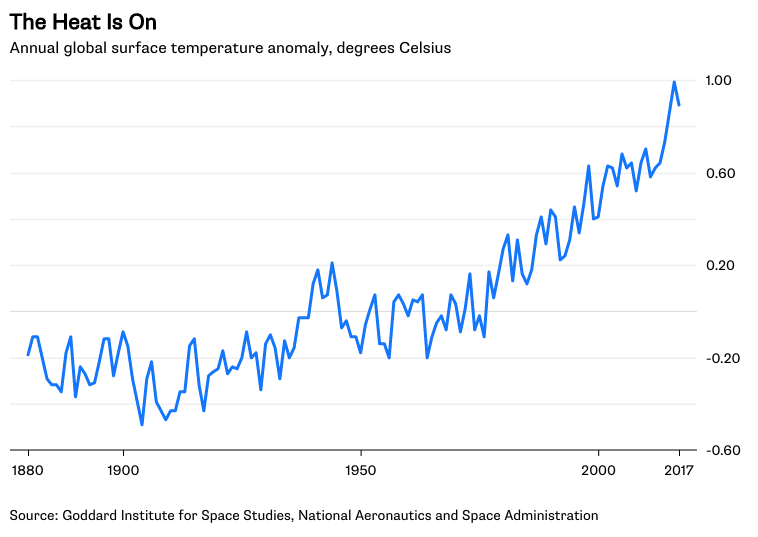

But this explanation, although true in general, doesn’t explain why there haven’t yet been at least a few well-publicized stories about coastal real estate prices crashing in specific areas. By now, the fact of climate change has been well documented. Charts showing rising temperatures abound:

Similarly, it's widely accepted that rising temperatures are projected to raise sea levels. How much, exactly, is a difficult question. Forecasts have generally predicted a rise of 1.7 to 3.2 feet by 2100, though some recent models say the increase will be significantly larger unless carbon emissions are substantially curbed. Zillow, a real estate website, estimates that a half-million homes in Miami could be underwater by century’s end, and has issued warnings for a large number of locations.

The turn of the century, though, is a long way off. Most markets don’t depend very much on things that are projected to happen many decades in the future—the Internal Revenue Service counts the useful life of a rental property as only 27.5 years, and the longest-dated U.S. Treasury bonds are only 30 years. Even in the worst-case scenario, sea level rise will be moderate by 2050—perhaps 1 or 2 feet along most U.S. east coast locations. And there’s a good chance it will be much less.

A rise of that magnitude doesn’t sound like a lot. But it would inundate a number of low-lying coastal areas. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s sea level rise viewer app lets you play around with the data and look at maps. Even a moderately bad climate-change scenario could swamp some pieces of coastal real estate within a few decades.

But sea level rise isn’t a gradual, steady thing. The ocean is not a still bowl of water, but a roiling mass tossed around by winds and tides. Long before coastal areas are permanently underwater, they’ll experience increased risk of catastrophic flooding. Hurricane Harvey, which last year flooded much of the city of Houston and became the second most expensive natural disaster in U.S. history (behind another wind-induced coastal flood, 2005’s Hurricane Katrina), is probably a harbinger of more frequent storm-driven disasters.

So for the next few decades, climate change probably won’t send coastal real estate prices crashing, but it does create a tail risk for buyers. Increased probability of coastal flooding makes waterfront real estate a bit like a junk bond—something that will probably go up in value, but has a small to moderate chance of going to zero. Junk bonds generally don’t have a value of zero, but the risk of devastation definitely does depress their selling price.