The inflation story took a turn for the better on Thursday when the government reported that the consumer price index fell 0.1% from a month earlier. Policymakers at the Federal Reserve will play down the report’s significance and reiterate their commitment to keep fighting volatile prices. But in private, they have to be elated.

Consider the situation from the Fed’s vantage point. Less than two months ago, Chair Jerome Powell laid out his framework for thinking about inflation in a speech at the Brookings Institution. Today, most of his hopes and dreams are already being realized. Supply chains are healing and core goods prices are cooling while forward-looking gauges of market rents signal shelter inflation is poised to come down soon as well. Perhaps most important, central bankers have received encouraging evidence regarding core services excluding shelter — that all important, wage-driven component of CPI that Powell feared would be the hardest to tame.

Indeed, after stripping out rent and owners’ equivalent rent, core services prices are rising at an annualized pace of just 2.6% over the past three months. When Powell gave his Brookings speech, annualized three-month inflation in that category stood at 7.1%. Now, it’s essentially back to its pre-pandemic average.

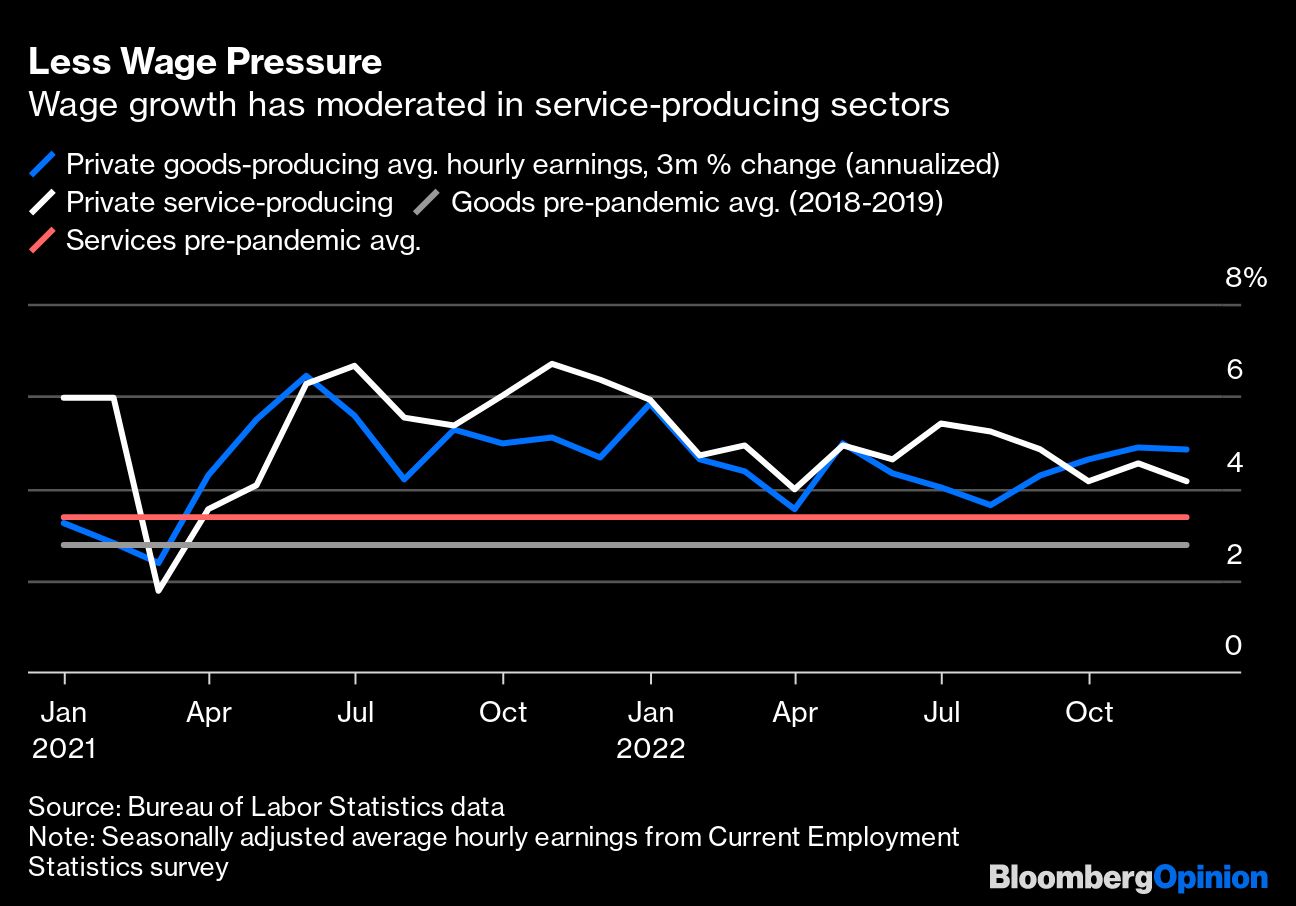

Even before Thursday’s report, there was growing evidence that inflationary pressures were ebbing in core services outside of housing. An Institute for Supply Management report on Jan. 6 showed a measure of prices paid by service providers declined for a second month. Meanwhile, increases in average hourly earnings — which Powell has flagged as a chief potential driver of service sector prices — have moderated significantly. While wage growth is running above pre-pandemic norms in both the goods and services sectors, the latter has experienced a sharp downswing.

Of course, Powell and his colleagues will continue to argue that inflation remains “too high,” but this is something of an oratorical trick. If traders sniff out lower inflation and the end of interest-rate increases, markets will rally further such that bond yields and borrowing costs will drop, and — in the Fed’s view — that could revive inflation. In a technical but misleading sense, it is true that the Fed is still missing its 2% inflation target. With the latest report, the year-over-year change in the headline consumer price index stands at 6.5%. That should leave the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the personal consumption expenditures deflator, at around 4.7%, according to Bloomberg Economics calculations — well above the 2% target. The Fed will probably raise interest rates by an additional 50 basis points or so to make sure it gets the job done.

But in a practical sense, the central bank isn’t actually missing its target by much, and a shift in policy is very much in play toward the end of the year. Changes in the CPI measured year over year are highly subject to base effects, meaning they say as much about where prices were in December 2021 as December 2022. Prices are not going up much right now. Based on the past three months of core CPI data, the annualized rate of inflation is running at just 3.1%. Using headline inflation, prices are up just 1.8%.

Clearly, there are some blemishes in the report — that cooling in shelter CPI still hasn’t truly materialized despite the leading indicators — but there can be no question that the overall inflation picture looks bright. Not only that, but it’s the third report in as many months that supported that conclusion, which means it’s probably not a fluke. Bond markets have taken note, with the yield on the two-year Treasury note declining six basis points to 4.16%, headed for its lowest close since Oct. 5. The S&P 500 Index dipped slightly, understandably, because lower inflation doesn’t preclude a recession and a concomitant drop in earnings. Higher interest rates take a while to bite and often with harsh and unintended consequences.

Another spike in prices is certainly possible, like the one that occurred toward the end of the 1970s after Fed Chair Arthur Burns famously thought he’d beaten inflation in 1976. We can’t rule out the notion that there are bigger structural issues at play here that call for a long-running war on inflation. But using Powell’s own criteria, there can be little doubt that this particular battle is almost over — no matter what the Fed chair and his colleagues ultimately say in public.

Jonathan Levin has worked as a Bloomberg journalist in Latin America and the U.S., covering finance, markets and M&A. Most recently, he has served as the company's Miami bureau chief. He is a CFA charterholder.