Is it just the same old song? When a bull market lasts as long as this one has, value investors can be expected to start singing the blues. First, cheap equities become difficult to find. Then market leadership tends to narrow. Pretty soon, frustration can test their resolve.

Is it just the same old song? When a bull market lasts as long as this one has, value investors can be expected to start singing the blues. First, cheap equities become difficult to find. Then market leadership tends to narrow. Pretty soon, frustration can test their resolve.

President Trump’s election and his emphasis on domestic manufacturing was expected to stimulate value stocks in the old economy and, in the months of November and December, it did. But the boomlet in value stocks stalled out by February, while new economy equities resumed their ascent.

In early May, GMO’s widely respected founder, Jeremy Grantham, sent a quarterly letter to investors that underscored some of the tribulations that disciples of value legend Ben Graham are experiencing. The very title of his letter, “This Time Seems Very, Very Different,” invoked what many consider the most dangerous words in investing. Coming from a value investor with Grantham’s intellect and certitude, the piece raised eyebrows.

Since 1996, the world has undergone dramatic changes, some good, some not. Medical breakthroughs have extended longevity, but terrorism is now a fact of life, placing the problems of investors in proper perspective.

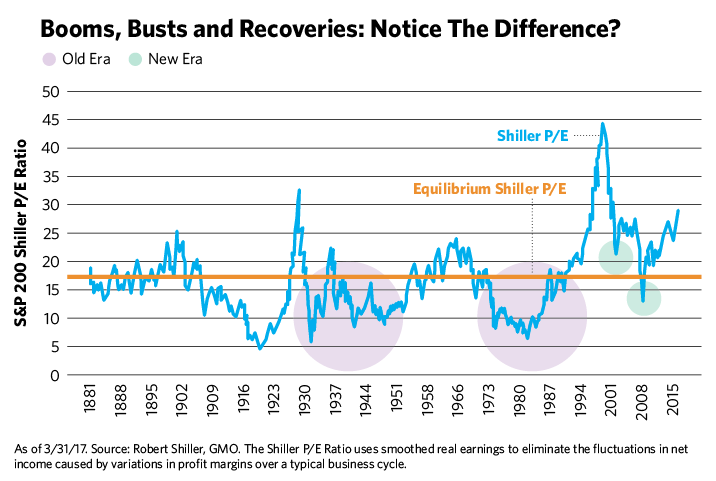

That said, equity investors have faced a market where the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 has been consistently higher than it was in the 1935-1995 era. “It has oscillated the same as before, but was now around a much higher mean, 65% to 70% higher,” Grantham wrote. “This is not a trivial difference to investors, and 20 years is long enough to test the apocryphal Keynesian quote that markets can stay irrational longer than the investor can stay solvent.”

After the tech bubble burst in 2000, a funny thing happened—the Shiller CAPE (Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio) failed “to go below trend even for a minute.” Grantham conceded that, at the time, he missed the full significance. “Even in 2009, with the whole commercial world wobbling, the market went below trend for only six months,” he wrote.

In the past, equity prices as measured by the equilibrium Shiller P/E had remained below trend for several decades after classic bubbles burst in 1929 and 1972. In the last two severe bear markets, the story was different. “It can be very dangerous indeed to assume that things are never different,” he warns.

What has changed? Three factors—lower interest rates, coupled with the surge in corporate profits and profit margins—are the primary driver of persistently higher P/E ratios in Grantham’s view.

Current stock-market skeptics attribute today’s lofty prices mostly to distortions arising from low interest rates resulting from accommodative central bank policy. It’s certainly a factor, but rates were modest in the 1930s, 1950s and early 1960s and multiples weren’t nearly so high.

Moreover, the high-price phenomenon described by Grantham existed for 12 years before the Great Recession, when debt costs were significantly higher than they have been since. Since 1997, P/E multiples have ascended to a much higher level and have failed to revert to the mean the way they once did during business cycles.

One factor is the combination of low interest rates and higher corporate leverage that distinguish the post-1996 era. Before then, interest rates were 200 basis points higher on average while leverage was 25% lower. Were those conditions to reappear, he estimates S&P 500 profit margins would drop 80% of the way back to pre-1997 averages.

Increased corporate power, which Grantham calls “the defining feature” of American history over the last 40 years, is also contributing to corporate profit margin expansion. Viewed from another vantage point, the percentage of unionized workers in the labor force fell from 35% in 1954 to 11% last year. In his view, rising corporate and monopoly power also subtracts from capital spending, GDP growth and job creation.

Since 2000, GDP expansion failed to reach a 1.9% average during either the Bush or Obama administrations, so many have good reason to ask why equities are doing so well. Seen from one vantage point, they haven’t. Eliminating 2000, the year the tech bubble burst, the S&P 500 has returned 5.63% from January 2001 to May 2017 with dividends reinvested. Yet it’s still triple the rate of GDP growth in that period, so it begs Warren Buffett’s question of how long the stock market can keep outpacing the economy. For quite a while, apparently.

When a business boasts abnormally high profit margins, economic theory presumes that new entrants will emerge, undercut established players to take market share and ultimately erode industry profitability. Yet Grantham maintains that many corporate giants possess near monopoly power and fewer businesses are being started as a result.

Against this backdrop of weak growth and productivity, companies that defy the mainstream get rewarded. Increased globalization has lifted the value of brands and the U.S. possesses more global brands than any other nation. Nowhere is American dominance more pronounced than in growth areas like high-tech, bio-pharma, social media and e-commerce, and those companies have driven the post-recession bull market. Yesterday’s global growth brands facing top-line challenges like Coca-Cola and J&J are today’s value companies, displaced by upstart disruptors like Amazon and Alphabet.

Grantham Asks: Is This Time Different Or Dangerous?

June 1, 2017

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment