Stocks in the mid-capitalization space are kind of like the overlooked middle child in a family with three children. Established large-cap stocks often receive the most attention, while small-cap stocks may offer the scintillating promise of future growth. Mid-cap stocks? Eh, they’re just kind of there.

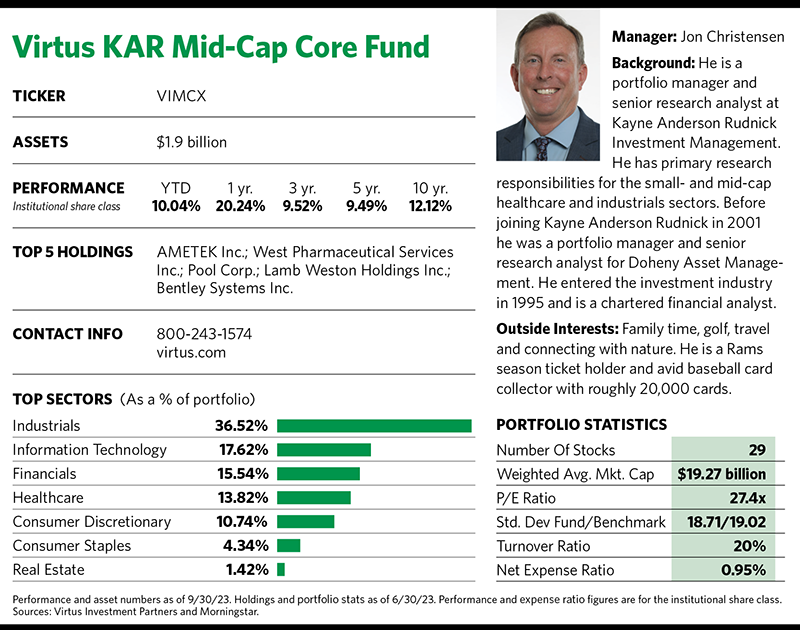

Of course, that’s an exaggeration. Then again, maybe not entirely. “People seem to overlook the mid-cap space. It’s a part of the market that I think is highly underinvested but which has amazing opportunities,” says Jon Christensen, co-portfolio manager at the Virtus KAR Mid-Cap Core Fund.

Companies in this space typically sit between $2 billion and $10 billion in capitalization, though that’s not an absolute rule. Christensen’s definition of mid-caps includes companies north of $10 billion. He also notes that some investors view mid-cap companies as being already mature. He disagrees with that assessment.

“I have this phrase, ‘Old enough to know, young enough to grow,’” he says. “These companies have graduated from small caps into mid-caps, so they’re more stable and profitable, but they’re still early in their business cycle and have room for much more growth.”

That’s why he thinks that mid-caps deserve more investor attention. “These are businesses just getting their mojo in terms of growth and penetrating markets,” he says.

Christensen and co-manager Craig Stone have been at the helm of the Virtus KAR Mid-Cap Core Fund since it launched in 2009. And they’ve earned their keep by producing returns that have placed the fund in the top quartile of Morningstar’s mid-cap growth category during the past one-, three-, five- and 10-year periods. During those times it has ranked anywhere from fourth to seventh place among the best-performing funds in its category.

So why is a mid-cap core fund placed in the mid-cap growth category?

As Christensen explains it, Morningstar ratings are focused on a company’s price-to-book ratio, and a high price-to-book usually equates with higher growth. He says that because his fund invests in high-quality businesses that are less capital intensive, the “book” in its price-to-book ratio is lower, and the higher resulting ratio lands the portfolio in the growth category despite its otherwise “core-ish” characteristics. Christensen defines “core” as the middle ground between value and growth.

The Quality Factor

The “KAR” in the fund’s name stands for Kayne Anderson Rudnick, a Los Angeles-based asset management and wealth management firm that’s among the nation’s largest RIAs. Its parent company is Virtus Investment Partners, a publicly traded holding company of boutique investment managers.

“[The wealth advisory business] is right down the hall from me,” says Christensen, who’s on the asset management side. “We are part of the same firm, and we have a relationship with them, but in general we try to keep things separate.”

Kayne Anderson Rudnick investment management’s philosophy focuses on three basic tenets—high-quality businesses, a lower-volatility approach and a high-conviction portfolio. “Quality is a business characteristic,” Christensen says. “We want to find companies that can grow, protect and nurture a market over long and multiple economic cycles. The ability of companies to hold up well in down markets and lower that downside capture will let us enhance compounded returns.”

With those traits in mind, he and Stone look for business models with wide defensible moats. “It could be a strong brand, a network effect, high switching costs or scale advantage,” he says.

Other attributes of quality include business models with less capital requirements, solid balance sheets and strong cash flow. “They shouldn’t need the debt or equity markets to grow their business, so our companies typically have less debt on their balance sheet,” he says.

He adds that good management is part of the quality equation—which means managers should demonstrate a good deal of inside ownership, boast a track record of being good capital allocators, and make sure their compensation is aligned with that of the company’s shareholders. “Management is key because they can take a good business and make it great,” he says, whereas questionable management “can run it into the ground.”

All this ties into Christensen and Stone’s emphasis on finding low-volatility companies with lower earnings variability, consistent growth and high returns on capital, along with the ample free cash flow and less need for external financing. “If you retain profitability during difficult times, your stock price should remain buoyant as well,” Christensen says.

This is reflected in the fund’s risk/reward profile. According to Morningstar, the Virtus KAR Mid-Cap Core Fund offers below-average risk and high-return potential for its category. Its upside capture ratio comfortably exceeds the category average, while its downside capture ratio is significantly lower than the category average.

Concentrated Portfolio

Because these are high-conviction names, the fund is concentrated and generally invests in only 25 to 35 stocks. The portfolio has a low turnover rate of about 20%, and the fund’s active share of nearly 90 means it has little correlation with its benchmark. (An active share score of 100 indicates that a fund’s equity portion and its benchmark have no common holdings.) “We hold fewer positions and have higher weight in those positions, so that’s why we have a high active share versus the benchmark,” Christensen says.

“We’re hired to be an active manager,” he adds. “We want to pick from the index, but we don’t want to be the index. Given our emphasis on quality, there may be certain sectors or areas of the market where we won’t invest.”

For example, the fund typically doesn’t own a lot of energy names because that’s a capital-intensive industry, one that’s highly levered and tied to volatile commodities. And the managers don’t invest in a lot of biotechs because many of those companies don’t have earnings.

“So certain sectors might be completely empty and we’ll be overweight other sectors as a result,” Christensen says. “We used to have more restrictions on our overweights and underweights, but we’ve gotten more liberal on that, and it has helped us in the end.”

The fund recently had nearly double the exposure to the industrials sector than its benchmark, the Russell Midcap Index. One reason for that is Christensen’s expansive definition of what the sector comprises.

Consider that one of the industrial sector stocks is Allegion, a maker of commercial and consumer security systems, while another is Equifax, the credit score company that Christensen acknowledges could be a fit in the financials sector as well. Other companies classified under industrials within the portfolio are Heico, an aerospace and electronics company; Lennox, which makes air conditioning units; freight company Old Dominion; water treatment company Pentair; and Verisk, a data analytics provider to the financial industry.

“They’re all very different end markets and business models, but they all have the same type of characteristics we look for in a high-quality business,” Christensen says. “It’s a more liberal characterization for industrials than the traditional GICS industrial category,” he adds, referring to the Global Industry Classification Standard widely used to categorize companies by sectors and industry groups.

Consistency

Christensen and Stone have known each other since they both worked at Doheny Asset Management in L.A. Stone came over to Kayne Anderson Rudnick in 2000, and Christensen followed the next year. As co-managers, they need to agree on all buy and sell decisions.

“He and I have worked together for many years and have a great relationship,” Christensen says. “The other important thing is how we work with our analysts. We have a good number of analysts helping us.”

He and Stone are analysts as well—Christensen covers healthcare and industrials while Stone covers real estate and consumer discretionary names. The portfolio’s concentrated holdings and low turnover aside, Christensen says the two managers keep busy by constantly monitoring their companies to spot any erosion in their competitive advantage.

“The biggest reason that prompts us to sell a stock is something that changes with the business,” he explains. “That means our initial investment thesis was incorrect or, more likely, the company’s advantage starts eroding. That’s why we have to keep monitoring our companies.”

He posits that M&A activity is the main reason companies fall off the rail. “When companies start doing M&A, it can indicate that its core business is slowing and they are looking for growth. The risk is that the deal could be outside of their core competency and that integration risks are high.”

When one of the fund’s companies makes an acquisition, Christensen says, the team makes sure it will be accretive and can be integrated without disrupting the core business. “Many companies can pull it off, but a lot of them can’t.”

In the final analysis, he credits the Virtus KAR Mid-Cap Core Fund’s long-term success to its disciplined investment approach. “We know that over the long term high quality will win out over low quality,” Christensen says. “We won’t pivot to buy low-quality businesses when low quality is in favor just to chase performance. The discipline we stick with accounts for our consistent performance.”