Senator Elizabeth Warren posted an online crisis alert on Monday warning that the U.S. is repeating the mistakes that led to the Great Recession. Warren argued that the rise in household and corporate debt has made the economy fragile and vulnerable to shocks.

This type of argument is usually associated with more conservative Wall Street types, sometimes as a rationale for returning to the gold standard. As Warren does, they fault the U.S. Federal Reserve for making it too easy for banks to lend to shaky borrowers. Gold-standard conservatives go a step further, arguing that the Fed should raise interest rates in order to quell the growth in debt. Warren hasn’t called for that yet, but the logic is simmering under the surface.

As long as interest rates are low, consumers and businesses will have an incentive to take on more debt. Low interest rates tend to lower banking-industry profits. To compensate, banks tend to take on riskier loans and engage in complex financial engineering to reduce their exposure to potential defaults. This has the side effect, however, of increasing systemic risk throughout the economy.

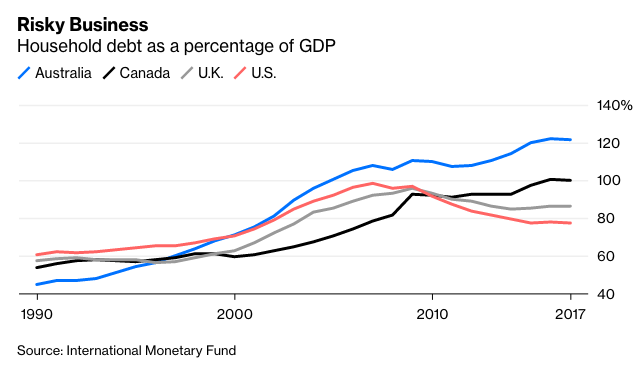

That’s true not just for the U.S., but around the world. In much of the English-speaking world, the ratio of household debt to the gross domestic product is actually higher than in the U.S. That’s because English common law gives local governments broad powers to restrict real estate development. In the resulting absence of big residential construction projects, single-family homes are the norm, and low interest rates have fueled a bidding war, driving up home prices and mortgage debt.

Does that mean that Warren and the gold-standard conservatives are right that the U.S. economy is on shaky ground? In a sense yes, but not for the reasons they think. What both miss is that low interest rates are driven by economic realities that can’t so easily be changed.

In Japan, where housing is less regulated and mortgage balances lower, the central government itself has taken on loads of debt. Japan’s ratio of government debt to GDP is nearly 200%. Around the developed world, low population growth and low inflation have driven down the neutral rate of interest at which an economy is neither speeding up nor slowing down.

If the Fed had tightened credit, either by raising interest rates or restricting lending, the recovery from the 2009 recession would have slowed and, as in parts of Europe, possibly stalled. Even now, the Fed is rightly concerned that that credit is too tight and is widely expected to lower interest rates.

Does that mean that developed economies are doomed to remain in a perilous boom-and-bust cycle? No, though fixing the problem won’t be easy. The first step is to try to increase inflation. Higher inflation would reduce household debt balances in two ways. It would raise the neutral rate of interest directly and would increase the rate of wage growth.

The higher neutral rate of interest would limit the maximum mortgage amounts that borrowers could qualify for and thereby cool the bidding war between home buyers. In addition, by making ordinary loans more profitable, it would reduce banks’ incentives to increase their income by offering riskier loans. That, in turn, would reduce home flipping and speculative purchases, both of which put upward pressure on housing prices.