The stubbornness of inflation continues to challenge and mystify central bankers worldwide. Whether they are trying to boost price growth or rein it in, policymakers are effectively wrestling with the same problem.

Consider Japan, which has experienced deflation (a decline in the price level) in 11 of the past 20 years. Since 2016, deflationary forces appear to have receded, but inflation rates have consistently remained well below the 2% target set by the Bank of Japan, despite accommodative policies. The BOJ has maintained the policy interest rate below zero since 2016, capped long-term rates near zero, and expanded the monetary base by about 250% since 2013 via record purchases of Japanese government bonds (JGBs). The BOJ now holds about 50% of the outstanding stock of government bonds. This is no small achievement, as Japan’s government debt ratio, at 238% of GDP, is the highest in the world. And yet, despite these policies, inflation expectations five years out are still anchored close to 1%.

At the other end of the spectrum, there is Argentina’s ongoing inflation battle. The Central Bank of Argentina (BCRA), in connection with an International Monetary Fund program in June 2018, promised to keep the monetary base unchanged. This has forced the policy rate to climb to almost 74%.

Nonetheless, the annual inflation rate has accelerated from around 26% a year ago to about 55%.

The pick-up in inflation largely reflects higher import prices, as the peso crashed (plummeting about 115% against the US dollar during the 12 months that ended in March). But pass-through from the exchange rate to the price level is only part of the story. And an overheated economy has played no role at all. On the contrary, Argentina is grappling with a deep and lingering recession. The IMF expects GDP to shrink by 1.2% this year (following a larger contraction in 2018).

And yet, despite a credit crunch and other indications of tight monetary conditions and a recent spate of price controls, inflation remains close to 40%. Under President Mauricio Macri’s administration, Argentina had a short-lived spell of inflation targeting during 2016-2018. When the scheme was unveiled, the 2019 target was set at within 1.5 percentage points of 5%. Credibility has been a problem.

Why have inflation expectations failed to respond to draconian changes in policies?

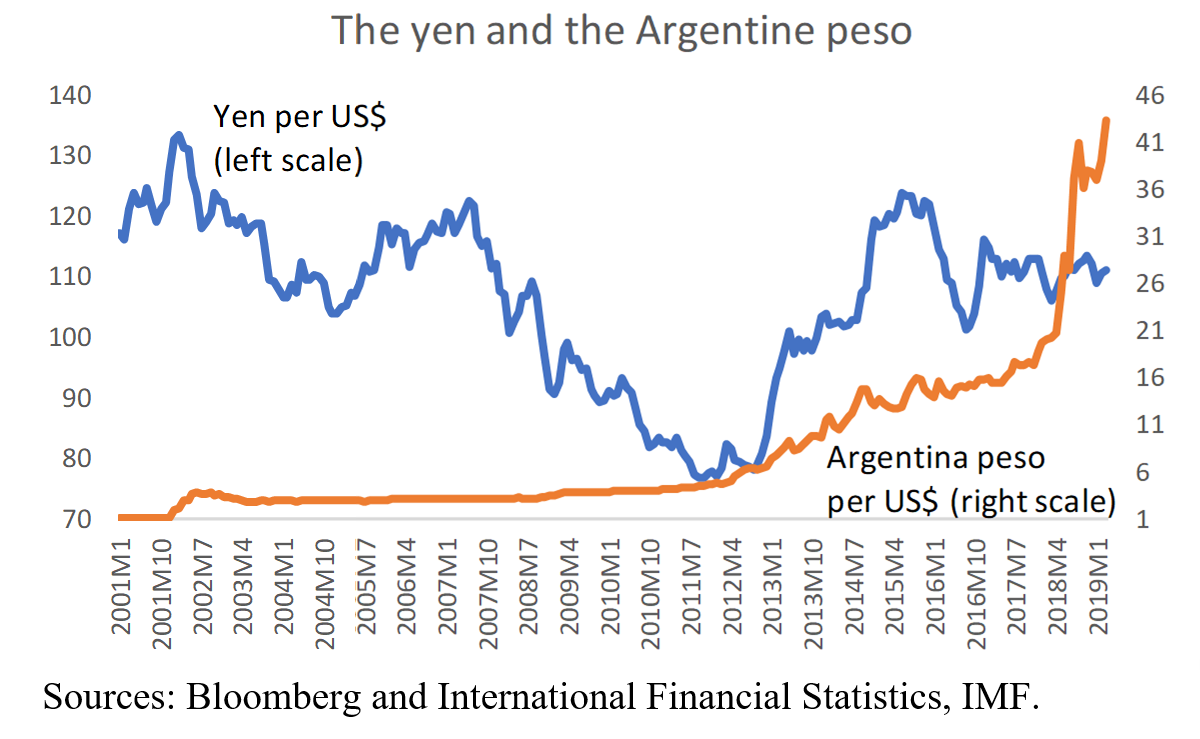

In 2001, one Argentina peso traded for one US dollar (see chart); today, one dollar costs around 44 pesos (a cumulative depreciation of over 4,000%). Since 2001, the Japanese yen has appreciated about 12% against the US dollar (and by almost 70% since the exchange rate began floating in 1971). Any modest amount of extrapolation would attach a low weight to a near-term yen crash or to a stable peso. During times of global financial market stress, there was a flight not only to US dollars (the global reserve currency), but also to yen (and swiss francs). In 2008-2009, for example, nearly all other currencies crashed.

These secular exchange-rate trends reinforce existing preferences in saving-consumption patterns and asset allocation. In the case of Japan (prior to the more recent era of negative real interest rates), they allowed savers to maintain the purchasing power of their savings. They also help to explain the strong Japanese bias toward domestic, yen-denominated assets.