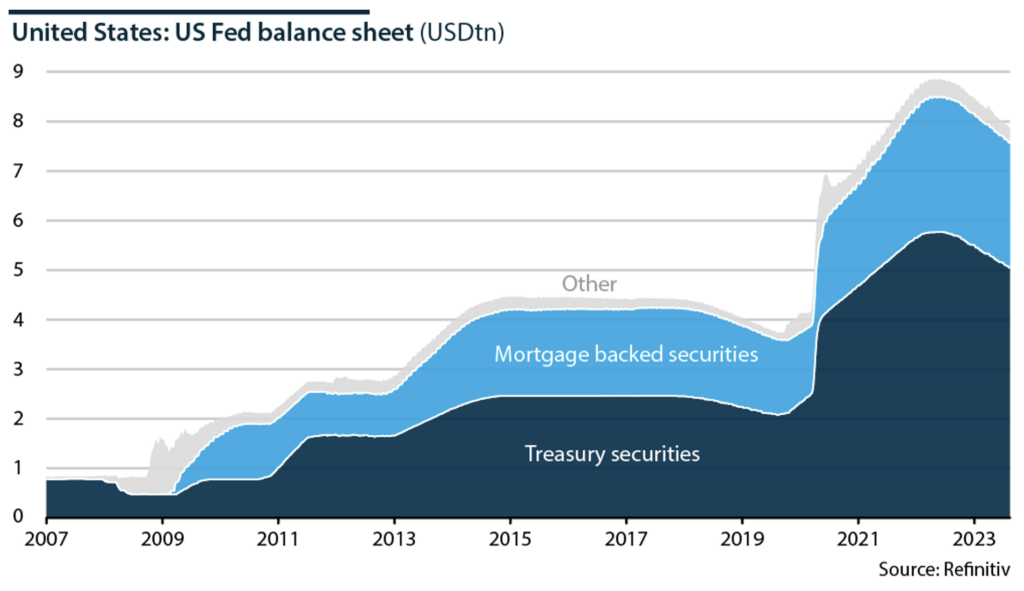

Central bankers and economists gather in Jackson Hole for their annual weekend symposium starting today with the U.S. Federal Reserve's balance sheet standing near USD8tn, several hundred billion below where it was in March 2023 before the Silicon Valley and Signature Bank bank runs.

It is down to around 31% of GDP from a peak above 36% in late 2021, when balance sheet reduction from pandemic highs started, and early 2022.

The Fed continues to reduce its balance sheet by USD95bn per month—USD60bn of Treasury bonds and USD35bn of agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS)—by not reinvesting the principal when securities mature.

The Fed's MBS holdings amount to USD2.5tn. It likely wants to reduce the number to zero, exiting the market. This would take six years at the current pace of trimming by USD35bn per month.

If the Fed chooses to slow its pace of overall portfolio sales, it would be more likely to reinvest in Treasuries to keep its effort to exit the MBS market on track.

The crucial question is how far the Fed will go to reduce the balance sheet.

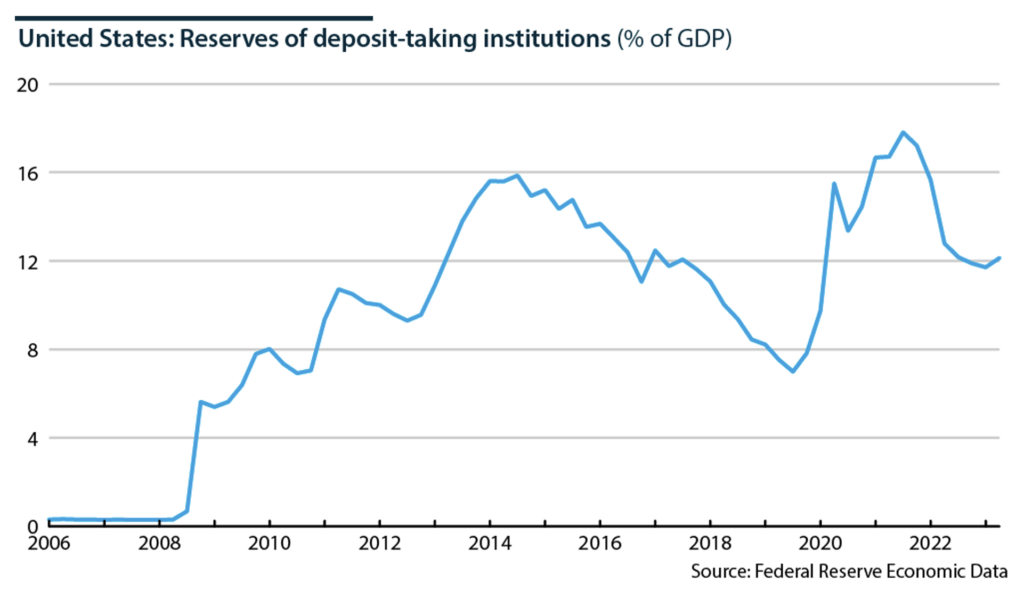

Bank Reserves

It appears to be concerned with the bank reserves it holds. Bank reserves are down from a peak of roughly USD4tn or 17% of GDP in 2021 to around USD3.2tn or 12% of GDP.

During the previous quantitative tightening in 2019, bank reserves dropped to around USD1.6tn (around 7% of GDP), and there was a “plumbing problem” or liquidity squeeze in financial markets: overnight repo market rates surged.

The Fed says it will halt balance sheet reductions when reserves are at an "ample level," but there is no common understanding of what this means.

The Fed could start to slacken the pace of sales as early as later this year or as late as 2025. At the current rate, and assuming steady but very modest GDP growth, bank reserves will be down to 7% of GDP, the 2019 level, by about the end of next year.

The balance sheet would be 25% of GDP or less by the end of 2024, where it was just before the pandemic.

Fed Chair William Powell claims that he is better prepared to face problems this time due to the experience gained during the 2019 crisis. He says he will attempt to slow down and end quantitative tightening while reserves are still “abundant.”

A number of market participants worry that the Fed is selling securities too quickly. However, the experience of 2019 suggests that the consequences of further spikes in short-run rates would be manageable.

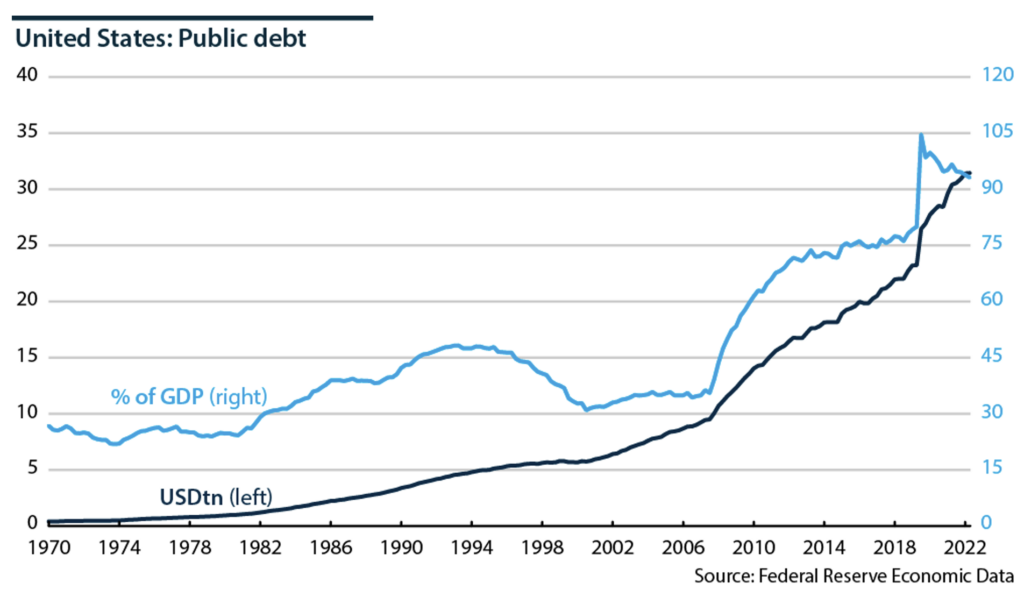

Debt Risks

U.S. public debt, now around USD31tn or 93% of GDP, is an increasing concern. The Fed views this as a consequence of federal fiscal policy and not an immediate concern of its own.

However, it is keen to avoid putting stress on the economy or financial markets through its policy moves.

The rising debt and the increasing cost of financing that debt may significantly impact the economy in the next few years.

This makes keeping inflation low and steady even more important, as financial markets assume that stable 2% inflation tends to lead to more moderate interest rates, keeping government borrowing costs down.

However, the recent 4%-plus 10-year treasury yields—pushing long-term rates into real territory—suggest bond investors expect rates to remain elevated for a while.

Higher for longer, with the emphasis on the length rather than the height, may well be the main theme in Jackson Hole this weekend.