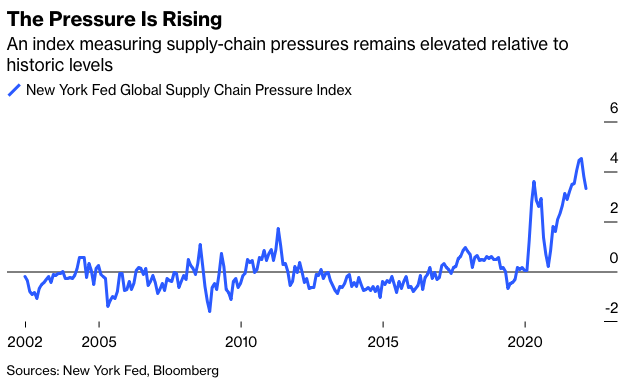

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis President Neel Kashkari published an essay Friday in which he admitted an uncomfortable truth. He wrote that if the supply-chain disruptions don't resolve soon, the U.S. Federal Reserve may be forced to spur a recession.

Kashkari pointed to the war in Ukraine and lockdowns in China's related to Covid-19 as reasons why supply chains haven't returned to normal as quickly as many expected. And if factories, shipping lines and commodity producers don't start operating more smoothly in the near future, "then we will likely have to push long-term real rates to a contractionary stance to bring supply and demand into balance," he added. In other words, such an outcome would force the Fed to raise its target for the federal funds rate, currently a range of 0.75% to 1%, well above the 3% that is priced into the futures market by February 2023.

Although the thoughts come from a Fed official who doesn’t vote on monetary policy this year, they are still alarming and should be taken seriously. For one, they underscore the limits of the central bank’s ability to control key drivers of inflation right now, including a war that has upended oil supplies, causes prices for crude and energy overall to spike higher, and lockdowns in China that are preventing goods from getting to such companies as Adidas AG and Under Armour Inc., causing them to lower their earnings forecasts.

After all, Fed members can't manufacture computer chips, control China's tolerance for Covid-19 cases or drill for oil. Central bankers have much blunter tools for an unprecedented moment in the economy: they mostly can simply squelch demand to bring it more in line with curtailed supplies of goods and shortages of labor.

This is the scenario that keeps economists up at night. It's the nightmare of stagflation, in which central bankers face both surging inflation and slowing growth and can't do anything about it, or, even worse, need to find a way to weaken the economy to ease price pressures.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey gave the markets a taste of this on Thursday when the U.K. central bank raised rates but also issued a gloomy outlook of double-digit inflation and prolonged stagnation—or even recession. The European Central Bank faces a similar scenario that it will have to address at its monetary policy meeting in a month’s time.

The U.S. economy, on the other hand, doesn’t appear to face an immediate threat from stagflation. The nation's labor market is robust, with the unemployment rate hanging around 3.6%, just a touch above the half-century low reached before the pandemic, and consumers and companies are less leveraged and better capitalized than in the past.

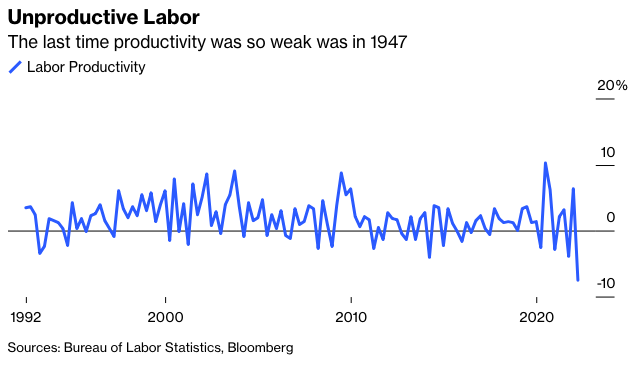

But there are signs the economy is moving in the wrong direction. Consumers and companies are getting less bang for their buck at the same time there is a shortage of goods. Data released Thursday by the government showed a drop in worker productivity and an increase in labor costs. The outlook corporate earnings per share growth in the remaining nine months of the year dropped last week to levels last recorded at the beginning of April, according to Bloomberg Intelligence equity strategists Gina Martin Adams and Gillian Wolff.