Pzena Investment Management is a value investor’s value investor. We’re not talking relative value, we’re talking deep value. That’s illustrated by the Pzena Emerging Markets Value Fund, where as of June 30 the portfolio’s valuation multiples—price-to-earnings/book/sales/cash flow—were all significantly less than those of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. And with the exception of price-to-cash flow, they were also lower than the multiples on the MSCI Emerging Markets Value Index.

Finding off-price items is great, but it’s pointless if you’re buying junk that deserves to be sold at steeply discounted prices. Successful bargain hunters have a knack for separating gems from the rubbish, and the folks who run the Emerging Markets Value Fund have built an impressive track record that shows they have an eye for spotting mispriced merchandise.

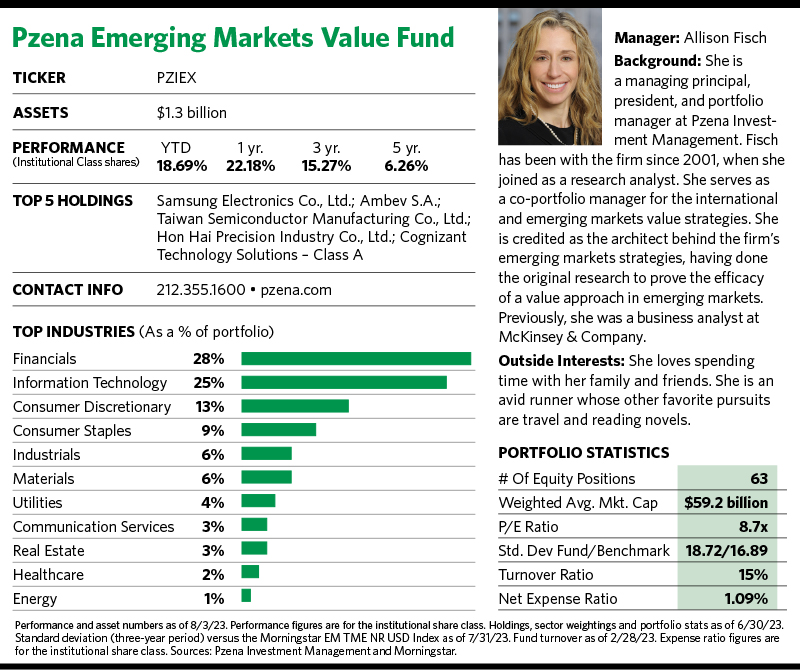

As of July 31, the 6.60% annualized five-year return on the fund’s institutional share class offering trounced the returns of both the MSCI Emerging Markets and MSCI Emerging Markets Value indexes by roughly five percentage points. The disparities are much wider—at double-digit percentage point levels—on the fund’s three-year average return of 16.15% and its one-year return of nearly 25%.

From its beginning, Pzena (pronounced “pa-zeena”) has been hyper-focused on value investing. The New York City-based firm was founded in 1995 by Richard Pzena, former chief research officer and director of U.S. equity investments at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. The company’s mission statement at its inception said it wanted “to be considered among the premier value investors globally.”

The firm has built a sizable book of business with roughly $56 billion in assets under management, mainly via separately managed accounts with big institutions. It also subadvises portfolios for a half dozen other fund companies, including four funds at Vanguard. It began rolling out Pzena-branded mutual funds in 2014. Of course, all of this is done under the rubric of value investing.

Normalized Earnings

Pzena measures value by using normalized earnings to paint what it says is a more comprehensive picture of a company’s long-term earnings potential. Normalized earnings are what a company is expected to earn across a business cycle.

“If a company is cheap relative to its normalized earnings power which they should earn in a mid-cycle benign environment, it means something bad is happening and the market is treating the company as if it’s a permanent impairment to that business,” says Allison Fisch, a portfolio manager at the Emerging Markets Value Fund.

“The job of our research team is to figure out if that’s the case, because if it’s only a temporary impairment then the market has it wrong and the earnings will improve and so will the stock price. That’s the philosophy we follow across the globe.”

Many people equate emerging markets with growth investing, but Fisch posits that value investing has been a path to outperformance in emerging market investing.

Perhaps, but emerging markets as a whole have been a chronic underachiever in recent years. According to index provider MSCI, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index has greatly underperformed both the MSCI All Country World Index (a measure of broad global equity-market performance) and the MSCI World Index (which is focused on equities in developed markets) during the past three-, five- and 10-year periods.

This, despite the sector’s oft-mentioned selling points that include a largely youthful demographic profile striving for middle-class status, coupled with its potential for faster economic growth than that of the developed markets. Meanwhile, one of the constant storylines about emerging markets stocks is that they’re cheaper than U.S. and other developed market equities.

“Emerging markets clearly have higher GDP growth potential,” Fisch says. “The valuation discount largely comes from the perception of increased risk that comes with investing in these emerging economies. You don’t have the same level of regulatory oversight or legal structures around corporations and investments, and you tend to have more currency and political volatility.”

She acknowledges that the sector as a whole has been an underperformer in recent years, but notes that much of the disappointment is due to slower economic growth in China, which is a huge part of emerging markets indexes. “But other [emerging] markets have performed quite strongly,” she says.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Indeed, emerging markets aren’t a monolithic sector, and that’s where Pzena’s research chops come into play. Fisch is one of four portfolio managers on the Emerging Markets Value Fund. She and Caroline Cai have been at the helm since the product launched nine years ago. (In addition to her portfolio manager duties, Cai became Pzena Investment Management’s CEO this past January.) Rakesh Bordia joined the PM team in 2015, and Akhil Subramanian came on board at the start of this year.

They’re backed by a sizable research team of analysts divided by industry coverage globally. The way it works is that portfolio managers screen for new investment ideas within the fund’s investment universe of the 1,500 largest emerging market companies. Their proprietary model zooms in on those stocks trading in the lowest quintile based on price relative to normalized earnings, and companies that look interesting and merit further research get assigned to the analyst who covers that industry for the firm.

What happens next is a two-part process. The first is an initial review period where the analyst gets a basic understanding of the company—what it does, how it creates value and what’s the negative event that caused its stock to head south. Once the analyst reaches a preliminary hypothesis on that, he or she will bring a research model packet into the research review meeting and discuss it with the investment team. At that stage most ideas get rejected, Fisch says.

For the few that make it past the initial screen, the next step is doing a deep-dive research project. That includes visiting the companies and analyzing every potential issue to arrive at a fully researched view on the normalized earnings power of the business.

“After all of that work is done we bring the company back into our research review meeting where we finalize our quantification of the issues and whether to buy the stock,” Fisch says, adding that all four portfolio managers have equal say over portfolio decisions.

The fund typically holds 40 to 80 stocks; it recently held roughly 60 positions. One of its largest holdings, Ambev S.A., typifies how the fund’s research approach zeroes in on potential candidates.

Ambev is a Brazilian brewer that Fisch describes as the leading beer distributor in Latin America. She notes that the company got quite cheap during the Covid-19 pandemic for various reasons. First, beer sales went down as the economy weakened. At the same time, the cost of inputs—which are priced in dollars—got very expensive and the company couldn’t push that through in price hikes because of the weak economy.

Ambev was further hurt by the pandemic shutdown of so many bars and restaurants—the most profitable channels for its products—and the company’s increased reliance on beer sales in grocery stores didn’t help its margins.

“The market treated that like it was going to be sustained in perpetuity,” Fisch says. “Our job as a research team is to figure out what really is the case and how things will possibly shake out over the short, medium and long term, which is what we’re really concerned about.”

After a thorough due diligence process, the portfolio managers determined that Ambev’s earnings power would be restored as conditions normalized and that the company’s strong balance sheet was a buttress against lean times. And so they added it to the portfolio.

The fund has a low turnover rate of 15%. Stocks are jettisoned when they reach estimated fair value based on their normalized price-to-earnings multiple.

Down … And Up

Like most funds with solid track records, the Emerging Markets Value Fund hasn’t been immune to slumps. In particular, it landed in the bottom quartile in Morningstar’s diversified emerging markets category in both 2019 and 2020.

Fisch explains that 2019 was a year where growth outperformed value by a wide margin. Meanwhile, value investors across the board got a whipping in early 2020 during Covid’s apex, which devastated many developing nations before things rebounded during the latter part of the year.

She notes that while the Emerging Markets Value Fund trailed the broad emerging markets index both years, it outperformed the value-oriented emerging markets index. “We’ve outperformed in a very negative environment for value during those years.”

The fund has rallied during the past two and a half years with top-quartile performance, including a sizable win (on a relative basis) when it lost only 5.7% last year while its category lost 21%, the MSCI Emerging Markets index lost 20% and the MSCI Emerging Markets Value index lost 15%. And the fund’s year-to-date gain of 19% as of early August had doubled that of its category average.

Fisch attributes the fund’s recent run of heady success to its diversification and company-specific stock picking. And she again stresses that value investing works quite well in emerging markets.

“The reason for that is the same reason that value investing works anywhere, which is that investors are not entirely rational,” she says. “In times of emotion you see valuation spreads move in unexpected ways, and you see even more of that in the emerging market space where there’s so much more uncertainty and unknowns.”

And that, she emphasizes, is where the opportunity lies.