At the beginning of summer, The Financial Times ran a story: “Top advisers pull their clients’ investments out of hedge funds.”

What To Look For

That sounded pretty extreme.

In late July, Erik Morgan, senior partner at the $4 billion Seattle-based asset manager Freestone Capital, told Private Wealth his firm has reduced its hedge fund exposure from $500 million in 2011 to $150 million. “We were seeing managers caught in a challenging place,” Morgan explains, “cautious about how much further the market can rally and the likely blowback from rising interest rates, and this gave us pause.”

Protracted underperformance of the industry has certainly borne out Morgan’s concerns.

But if you look at total hedge fund assets, they closed the first half of 2017 at a record high of $3.1 trillion, according to leading industry data tracker HFR.

Hedge funds are not essential to anyone’s portfolio—individual or institutional. Many have been poor investments, especially compared with the S&P 500. And while improving, their fees still weigh on net returns.

A key argument for hedge funds, however, is their ability to preserve capital during down markets.

In the middle of the Tech Wreck in 2001 and 2002, the average fund outperformed the S&P 500 by more than 42 percentage points; in 2008, industry outperformance exceeded the market by more than 15 percentage points, according to another leading data source, BarclayHedge. But from the beginning of 2009, the market has generated an additional 67 percentage points over the average hedge fund through June 2017.

Many observers would agree the S&P 500’s recent annualized growth rate—in excess of 14% over the eight and a half years since stocks cratered—is unsustainable. And unless one is a closet indexer, virtually all managers—hedge fund or otherwise—would invariably have lagged the market.

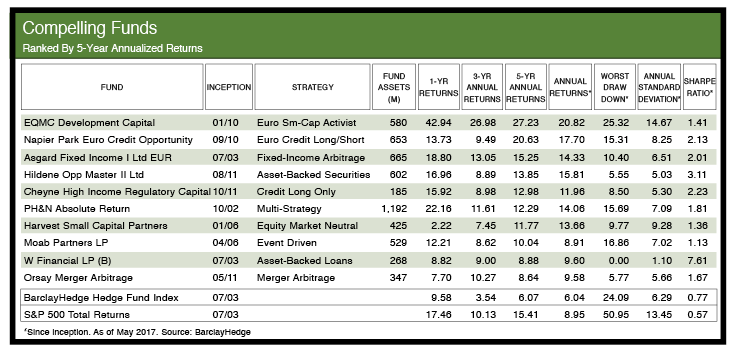

Since portfolios need to be diversified beyond the market, there are a number of unique hedge fund managers and strategies that are worth a look.

In our list below, you’ll find a fund that provides first-lien, low loan-to-value bridge loans focused primarily on quality New York City properties to qualified owners with immediate, short-term funding needs. Manhattan-based W Financial, run by Gregg Winter and David Heiden, has been filling a space neglected by traditional lenders with a precise, transparent, easy-to-understand strategy. Over its 14 years, the fund has never suffered a negative year or even a drawdown—because the value of the loans has never fallen below the value of the attached property. The $275 million fund has virtually no volatility and has racked up consistent net annual gains between 6% and 11%. The managers follow a disciplined investing approach and will only accept new money when they can put it to use.

A hedge fund based in Spain that has been around since 2010 has generated even higher annualized returns, nearly 21%, by doing something most other investors don’t—actively helping underperforming small-cap European companies realize their potential. The EQMC Europe Development Capital Fund, which runs $580 million, enjoys the benefits of being a small, nimble fund while being part of a large parent firm. Alantra Group is a $4 billion European asset manager that provides the fund with more robust administrative structure, financial and legal support, research and business links across the continent.

Managers Jacobo Llanza and Francisco de Juan operate the fund like a hybrid private-equity shop, concentrating on a limited number of companies, working with company managements that want help, and leaving firms better off than when they found them. This longer-term strategy comes with greater volatility, but so far the fund has justified the risks.

“We must get to know a manager well enough to trust and admire him [or her] before investing,” explains Alexandre Col, former partner of the venerable private bank Edmond de Rothschild and now co-manager of Geneva- and Luxembourg-based alternative asset manager Iteram, which manages 1 billion euros, 300 million of which is invested in hedge funds. His firm also wants to see a dedicated compliance officer to ensure funds follow their mandates and the ever-changing regulatory landscape.

Hilmi Unver, former CIO and now head of ultra-high-net-worth individuals and family offices at Swiss-headquartered Notz Stucki, an $8.5 billion asset manager with more than $2 billion in hedge funds, wants managers to be able to articulate a “strong, well-argued large-picture view of things to understand how individual investments fit into that thinking.”

The tax efficiency of a hedge fund must also be of concern to individual investors, explains Jeffrey Willardson, partner and head of portfolio solutions at PAAMCO Prisma, which has $30 billion invested in hedge funds.

Since the Tech Wreck, institutional investors—who don’t pay taxes on profits—have represented a growing percentage of the hedge fund investor base. They now represent more than three-quarters of all invested dollars. “That transformation has altered the way many funds are run,” Willardson says.

High-turnover strategies such as quant funds generate a lot of short-term profits, which are taxed at high personal income tax rates. Longer maturing strategies, such as distressed funds, expose individuals to lower long-term tax rates. Advisors should select funds according to their clients’ post-tax targets.

After a decade of tracking the industry, I’ve found nine additional features advisors should look for.

1. Look at smaller funds running between $100 million and $1 billion with at least five years of audited performance and top-tier service providers (prime brokers, administrators, accountants and lawyers); while there are a handful of multibillion-dollar funds that have solid long-term track records, it’s easier to find more opportunities and to exit them more profitably when dealing with managers running a much smaller amount of money. Responsible, smaller fund managers also tend to be extremely diligent and hungry to prove their worth.

2. Make sure managers are extremely well-versed with their investment processes, operations and risks; if they can’t describe what they’re doing succinctly and compellingly, move on.

3. Managers should have a substantial amount of their own wealth in the fund.

4. Make sure a fund’s strategy and assets are compatible with its liquidity terms. Many funds were forced to gate and suspend redemptions (which are death knells) during the financial crisis because of such mismatches. Features that can help address this risk include lockup periods and the prevalence of long-term investors, such as pension funds.

5. Management and performance fess should not exceed 1.5% and 20%, respectively, and look for hard hurdles that set an annual return threshold that a manager must exceed before earning a performance fee, which prevents payment for subpar returns.

6. Smaller fund managers tend to have a deeper appreciation for their investors and the need to maintain clear communication about what they are doing; if they begin to flail and their messaging becomes muddied, that’s a bad sign.

7. One of the most convincing indicators of a good hedge fund is its willingness to temporarily close to new investors when the manager doesn’t see enough quality opportunities to effectively put new capital to work; funds that are pure asset gatherers will have a harder time maintaining performance.

8. After taking extensive profits, a good manager who subsequently sees insufficient opportunities to reinvest may occasionally return capital to investors.

9. A manager’s willingness to cap the size of a fund is also a positive sign—showing his or her recognition that performance can suffer when the fund is trying to run too much money.

Finding The Right Hedge Fund

September 13, 2017

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment