Companies in the materials sector—think miners and steelmakers, for example—are typically shunned by proponents of so-called sustainable or environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing. So it might seem incongruent that the GMO Climate Change Fund is chock-full of holdings classified in the materials sector. We’re talking 27% of the fund’s portfolio as of January 31.

“Some people would be surprised to see copper or nickel miners or other materials companies in a climate strategy,” says Lucas White, the fund’s portfolio manager. “A lot of climate-oriented and ESG-inclined investors don’t want to invest in extractive industries. They don’t like fossil fuel or mining companies. Unfortunately, there is no clean energy without raw materials.”

According to GMO, the Boston-based asset manager formally known as Grantham, Mayo, Van Otterloo & Co. LLC, the Climate Change Fund looks for companies that will benefit from efforts to curb the effects of climate change—as well as companies aiming to improve resource consumption. Some of its target names supply the raw materials that go into products for combating global warming. But of course the fund also looks for names in wind power, solar energy, biofuels, battery storage and whatever else fits under the umbrella of cleaner energy and resource efficiency.

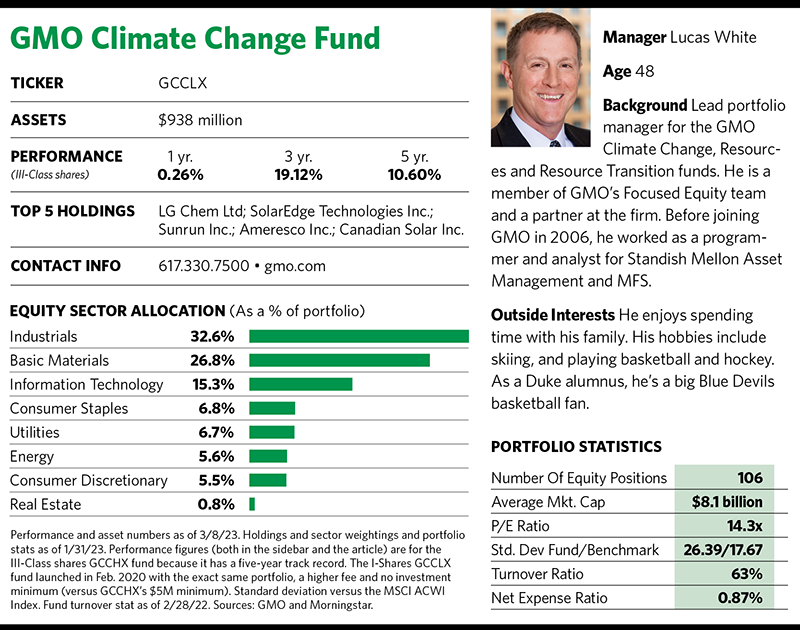

The fund has produced stellar results since it launched in April 2017, with top-quartile performance in Morningstar’s global small/mid stock category in the one-, three- and five-year periods (through March 8). The fund lost more than 10% last year, but even so it trounced category peers, whose funds plunged 26% on average. This year, through early March, the fund had gained 8.8% while the category average gain was 7.2%.

GMO co-founder Jeremy Grantham has been a passionate advocate for addressing climate change, and the firm believes that ESG factors can be drivers of successful investing.

The Climate Change Fund evolved out of the GMO Resources Fund that began trading in 2011 and which White has managed since 2015. He started thinking about how to design a natural resources strategy that took climate risks into account—even as fossil fuels typically make up 65% to 70% of this sector’s weighting. The Resources Fund has aimed to manage those risks in part by averaging about 35% in fossil fuels.

Over time, GMO realized that fossil fuels have been the past and present of energy, but that clean energy will be the future growth engine. By the middle of the 2010s, the clean energy complex was showing signs of becoming cost competitive with legacy energy sources and was gaining inexorable momentum.

“We saw transformational change in a number of industries, whether that be the automobile industry with electric vehicles, power generation and utilities, and steel- and aluminum-making,” White says. “We wanted to launch a strategy that capitalizes on that growth on transformational change.”

Being Picky

White says he pushed hard to launch a climate change strategy, and when he got the green light he found the process of getting the fund in shape to be “a major undertaking.”

“There’s no industry classification system you can use for climate change. When you look at GICS, you can’t identify solar and wind companies with it,” he says, referring to the global industry classification standard that categorizes industry sectors and subsectors. “We’ve had to go through more than 1,000 companies individually doing fundamental analysis to figure out whether a company fit or didn’t fit.”

He and his team approached it by looking at core principles and asking what was needed to combat climate change—as well as which industry sectors and individual companies made the grade.

“We had to figure out the different points in the value chain and their dynamics, figure out the key players and the like,” White says. They found, for instance, that the solar industry isn’t a monolith. It has companies with different specialties and business models.

He works with a handful of analysts to develop and maintain the climate change strategy, and he describes their work as a hybrid qualitative/quantitative approach. “We don’t have any quantitative screen regarding finding the universe and opportunity set,” he says. “We do enough fundamental analysis of every name in our universe that we’d be willing to hold it at the right price.”

Of the 1,000 or so companies they’ve researched, only about 350 names passed the test for further quantitative analysis. “That provides a sense of how picky we can be,” White says.

The quantitative analysis combines 11 value models that slice and dice companies’ profitability in various ways. “We’re not doing price-to-book or price-to-sales and the like that aren’t profitability related,” White explains. “We look at things that tell us how much money can this company generate on the behalf of shareholders relative to the price of the company.”

The end result is a portfolio with a few wrinkles. As White describes it, that means including companies you wouldn’t expect to find in a climate change-oriented fund and excluding companies you’d expect to be in there.

King Copper

Let’s start with the miners. Among the mining companies in the fund is top 10 holding Ivanhoe Mines Ltd., a Canadian miner with a big focus on copper. As White sees it, copper is foundational in efforts to combat climate change. “Copper is the oil of the clean energy economy. It underlies almost everything in clean energy.”

He notes that electric vehicles use three to four times as much copper as internal combustion vehicles, and that electric buses consume about 800 pounds of copper. Meanwhile, bringing a higher percentage of renewables into our energy mix requires an overhaul of electric grids worldwide.

“If you’re going to overhaul your grids you’ll need a lot of copper,” he continues. “Copper is the material of choice in electrical applications.”

In reality, he says, the great clean energy transition requires trading one set of natural resources—coal, natural gas and oil—for another set of natural resources in the form of copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, vanadium, silver and platinum. “It’s just a different set of materials. So we think materials play a big role in the clean energy transition,” he says.

Some miners can be bought at a good price, he argues. That’s because the market likely hasn’t priced in their long-term growth prospects.

More Than Just A Good Story

Among the recent top 10 holdings in the GMO Climate Change Fund are solar companies (SolarEdge Technologies Inc., Sunrun Inc. and Canadian Solar Inc.); wind turbine maker Vestas Wind Systems A/S; and renewable energy provider Ameresco Inc. Others on the list were lithium ion storage batteries supplier LG Chem Ltd. and biofuels company Darling Ingredients Inc.

The list also included BorgWarner Inc., an automotive supplier whose components go into combustion, hybrid and electric vehicles. The company plans to spin off two legacy business units aimed at combustion engines in order to focus on the electric vehicle market.

Another recent holding in the fund’s top 10, GrafTech International Ltd., produces ultra-high power electrodes for electric-arc furnace steel manufacturers. Recent studies found that electric-arc furnace steelmaking (which uses electricity to melt scrap and recycled metal) produces 75% to 85% less in carbon emissions than the blast-furnace steelmaking that relies on coal-distilled coke to melt pure iron ore.

And then there’s nuclear power, which is both praised as a vital cog in the clean energy machine and vilified and feared for its radiation risks.

White says nuclear fits within the fund’s mandate since it’s a clean form of energy generation. “It’s not something I need to have exposure to, but I’m happy to have nuclear exposure if I can find good investment opportunities.”

Ultimately, he says, he avoids companies that don’t have strong investment credentials—even if they do fit the climate change/clean energy narrative—so he doesn’t think something like clean hydrogen is ready yet for prime time. “We look for companies with strong profitability or imminent profitability, have strong balance sheets or have an identifiable edge,” he notes, adding that they have to be bought at reasonable levels.

“Since we incepted in 2017 our portfolio has always traded at a discount to the market—at an average 20% to 25% discount,” he notes. “That’s far different than buying Tesla or Plug Power or others trading at very high valuations, or those you can’t figure out what their multiple is because they don’t make money.”

ESG Backlash

There has been a recent backlash against the ESG movement over the last year. Critics in both financial and political circles have lambasted it as a tool of the left designed to impose its agenda on the public and investors at the expense of both corporate profits and consumers, who have been hit with high gasoline prices.

White offers that while some financial services firms have inappropriately applied or marketed the ESG concept, there is investor demand for these products and there’s nothing wrong with ESG or sustainability per se. “To me, ESG is just a subset of fundamental analysis that has been fenced off and rebranded by the industry.”

He says GMO hasn’t had significant pushback on its climate change strategy. “Some of that is self-selection. The kinds of people that are interested in the climate change strategy already buy into the thesis. The skeptics aren’t going to set up a meeting just to berate me. I also think it’s pretty clear that we’re approaching climate investing from a pragmatic, investment-driven standpoint [that includes mining companies].”