With tight valuations, quantitative tightening and rising rates, fixed-income investors have to navigate an evolving and challenging landscape. For investors seeking an alternative fixed-income risk, exposure to residential mortgage credit offers an investment opportunity, but is not without its own set of challenges.

Although the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Index has a sizeable exposure to agency-backed residential mortgages, sources of other securitized credit risk are underrepresented. Credit risk transfer (CRT), a relatively new and growing market segment, provides investors with a reliable source of otherwise elusive access to residential mortgage credit exposure. As the CRT market approaches its fifth birthday, we take a closer look at the evolution of this increasingly important market segment.

Credit Risk Transfer In A Nutshell: What Are Government Sponsored Enterprises Trying To Accomplish?

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) outlined a strategic plan to reduce the risk posed to taxpayers from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. As part of this plan, a primary challenge emerged: how to reduce risk to the U.S. taxpayer and the financial system, but do so in a way that preserves efficient and reliable borrower access to mortgage credit. To assist in meeting this challenge, the credit risk transfer (CRT) securitization market was created.

After years of planning and consultation with capital market participants and regulators, CRT issuance commenced in July 2013. Both Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae issued publicly registered securities, via Structured Agency Credit Risk (STACR) and Connecticut Avenues Securities (CAS) transactions. With the successful issuance of these fixed-income instruments, government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) effectively purchased protection against potential default risk from their mortgage borrowers via capital markets investors. The GSEs continued to collect their normal guarantee fees from lenders for covering borrower credit risk, but now compensated investors in STACR and CAS transactions for taking portions of that same risk.

How Has Credit Risk Transfer Evolved?

The concept of credit risk transfer is not new. Before the 2008 crisis, GSEs selectively used “front end” forms of credit protection tools such as primary mortgage insurance and mortgage insurance pool policies. The more recent “back end” efforts to transfer credit risk are different for two primary reasons: scale and structure.

While CRT transactions have evolved since 2013, all of the offered securities have been structured as uncapped 1-month LIBOR-based floating-rate securities. Securities pay interest and return principal monthly, mimicking the payments made by the underlying reference pool through time. Although the details vary by transaction, generally the GSEs are required to buy back the notes at par in 10 to 13 years and have the option to call the transaction at 10 percent of the original balance.

Different flavors of credit risk have emerged as investor acceptance of the CRT market has increased. Examples include transactions collateralized by borrowers with higher loan-to-value mortgages (i.e. >80 percent), transactions that pass through actual losses on resolved foreclosures (as opposed to prescribed loss severities) and sale of a portion of the first loss risk position. Future developments are likely to include regular issuance via vehicles that qualify as real estate mortgage investment conduits (REMICs), in an effort to increase investment sponsorship from REITs.

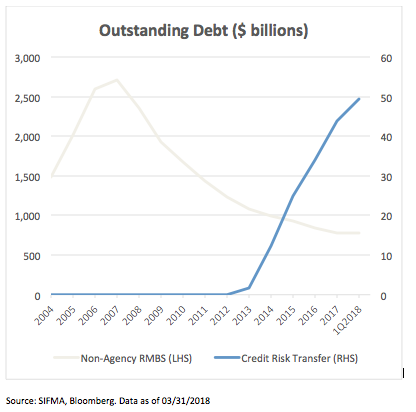

As the legacy portion of the non-agency RMBS market shrinks, credit risk transfer enables investors to maintain allocations to residential mortgage credit (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Growing Market For Credit Risk Transfer