With the U.S. economy booming, the job market growing and inflation retreating, the consensus is near-unanimous: Bidenomics has been vindicated. Allow me to offer a somewhat more skeptical perspective: Not that President Joe Biden’s economic policies have failed, necessarily, but that it is too soon to call them a success.

I fully concede that the U.S. has some pressing problems—deindustrialization, infrastructure deficiencies, climate change and national-security issues related to semiconductor chips, to name a few—and that Bidenomics is an honest attempt to address them. What I take issue with is this new variant of industrial policy based on heavy government subsidies to private investment. The centerpiece of Bidenomics is the Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022, whose cost could top half a trillion dollars.

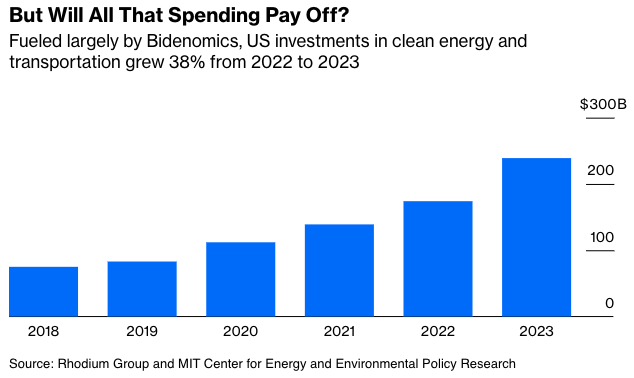

The biggest problem is that it’s not yet clear these investments are going to pay off. They are being paid for with borrowed money, not higher taxes or lower spending elsewhere. It is always possible to boost wages and employment in the short run by funding new investments with borrowed money. The critical question is whether those investments will succeed in the long run.

If they do not, today’s boom will eventually turn into a bust. Sooner or later, the federal government will have to pay for all this borrowing and spending, and that will mean some mix of (additional) tax hikes and spending cuts. That contractionary fiscal policy will hurt the economy, giving back some or all of the gains it is reaping today. The net effect of this reversal of fiscal policy could even be negative.

Conversely, if the new investments do succeed, future output will be accordingly higher, and those fiscal retrenchments will be manageable. Defenders of Bidenomics tend to assume this scenario, but its likelihood is an open question. By the same token, of course, critics of Bidenomics shouldn’t assume that the worse-case scenario is most likely.

Speculation about their future success, however, obscures a deeper question about Bidenomics’ investments: Are they wise? Or, to put another way: What’s the proper way to judge them?

After all, it is the scientific consensus that the world needs more green energy. I would state it slightly differently: What the world needs is to lower carbon emissions. It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which the U.S. has more green energy—and yet exports more oil and natural gas, stimulating the broader global demand for non-green energy.

It is not enough for the U.S. to be greener. The goal should be to produce new technologies that are sufficiently cheap that most of the world will want to be greener, too. That might happen with Bidenomics, but it is hardly certain. Any solution to climate change, looking forward, will have to address China, and to some extent India and Africa as well. A different approach would have been to subsidize cheaper green technologies for global adoption, but that is not what Bidenomics did.

One defense of the limited global scope of Bidenomics is that the most the U.S. can hope to do is to “take care of our own.” That may be true, but it does not alter the underlying reality. If the new investments do not bring about a significantly greener world, they will have failed. In a matter this serious, it really is about results.

Another possible outcome is more optimistic: Namely, the rest of the world will move to cheap green energy without needing support from Bidenomics. If that’s the case, however, then Bidenomics’ green-energy investments are still hard to justify. Why couldn’t the U.S. simply borrow cheaper technologies from the rest of the world?

The most favorable scenario for Bidenomics is that U.S. investments lead, through faster innovation and shallower learning curves, to cheaper green energy sources that otherwise would not have come about. Again, that is certainly possible. And again, it is hardly obvious that it is the most likely outcome.

Another notable feature of Bidenomics is that it tends to emphasize paying more to get more of something, rather than lowering its cost. Its subsidies for green energy, for instance, are much higher if businesses also invest in higher-wage green energy projects. Thus it favors costly forms of green energy over cheap forms. That brings into further doubt whether Bidenomics will encourage green energy on a global basis, as most countries cannot afford the same expensive technologies as the U.S.

The emphasis on jobs raises another question: Is Bidenomics trying to do too much? Harvard economist Dani Rodrik, the leading expert on industrial policy, stresses that successful industrial policy should be aimed at a single goal. “The more things you try to achieve, the less likely you are to get them,” he told the Financial Times last month. Ezra Klein has stressed a similar point in the New York Times, critiquing what he calls the “everything-bagel” approach to domestic policy.

It is also noteworthy that Bidenomics, on the climate front, has nothing resembling a carbon tax, which research shows makes climate industrial policy far more effective and fiscally much sounder. In all fairness, a carbon tax was and remains politically impossible. Nonetheless, it is important to distinguish two quite different questions: “Will this policy work?” and “Did we do everything we could have?” Unfortunately, a yes answer to the second question does not settle the first.

Bidenomics is more than the Inflation Reduction Act, of course. The $52 billion Chips and Science Act was designed to give the U.S. its own domestic semiconductor industry, to limit its reliance on Taiwan and South Korea, the current dominant producers.

The rationale is a good one, yet the implementation does not match the vision. The Biden administration has been slow to make grants, and problems with land use, permit permissions and environmental reviews have held up the planning process. There are shortages of skilled U.S. workers. Firms may also be reluctant to make commitments because it is hard to predict the future of both subsidies and the regulatory environment. It could be many years before the U.S. is producing high-quality chips of its own.

There has been some movement in Congress for permitting reform, to ease one of the many obstacles for chip production, and for that matter for green energy. And to its credit, the Biden administration has supported a version of permitting reform, but it hasn’t made it a priority.

And so as things currently stand, a chips plant can be built much more quickly and cheaply in Taiwan or Japan than in the U.S. Leading chipmaker TSMC just opened its first Japanese plant last month, with a second planned.

The core problem here is that the Chips and Science Act—like the Inflation Reduction Act, and Bidenomics generally—has a lot of expenditure but very little deregulation.

The obstacles to the construction of more chip plants are not financial so much as bureaucratic. Again it’s a matter of priorities. What is more important, making the US autonomous in the manufacture of high-quality chips? Or enforcing and tightening labor and environmental standards? The U.S. has to choose. So far, however, its government is not willing to.

What else counts as Bidenomics? Paul Krugman recently summarized Bidenomics this way: “major enhancements of Obamacare, student debt relief, big infrastructure spending, large-scale promotion of semiconductors and green energy that have led to a surge in manufacturing investment.”

The changes to Obamacare are largely a separate topic. But the Biden administration’s efforts on student debt relief strike me as emblematic of Bidenomics more generally.

Few major policies have occasioned so much opposition from economists, including Democratic-leaning economists , as the administration’s original plan. It could have cost as much as $430 billion, with the benefits aimed at those with some college experience. That is a group with above-average economic prospects, even though the highest earners were excluded from debt relief.

Fortunately, the courts struck down this plan, though the administration has continued with a much smaller version. And yet, the episode is instructive. When the Biden administration acted on its own, without guidance from Congress—unlike other parts of Bidenomics, the debt-relief plan was done by executive order—it came up with a plan that was both regressive and excessively costly.

I shouldn’t have to say—but I will—that all Americans should be rooting for the Bidenomics investments to pay off. To insist they will not is itself a dogmatic view. But the verdict is still out, and will be for some while. It’s far too early to be declaring victory.

Tyler Cowen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, a professor of economics at George Mason University and host of the Marginal Revolution blog.