Is it a good idea to hedge away currency exposure in international equity allocations? We think the decision to hedge or not to hedge is a nuanced one. Here are some of the considerations.

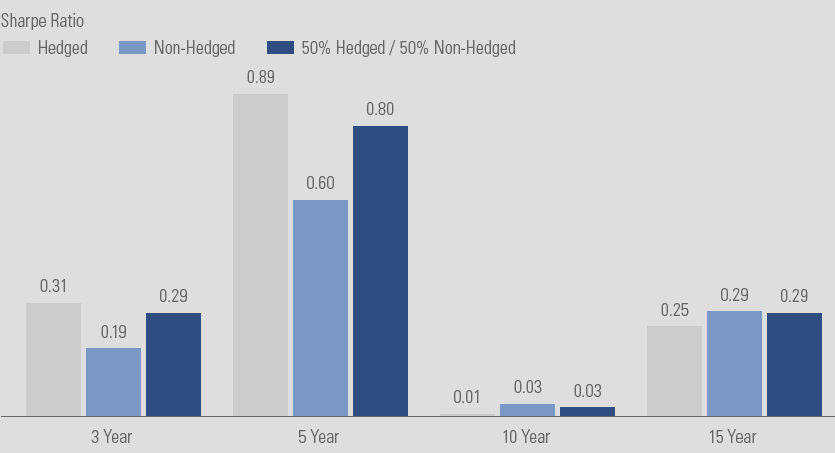

Currency hedging need not be an “either/or” proposition. Although the question is often framed as binary in nature, investors need not view currency hedging in black-and-white terms; diversifying across strategies often makes sense. One reason: timing can be critical. In the case of Japanese equities, the yen came under pressure after Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe assumed office in 2012, prompting a revival of interest in currency hedging. Yet, as Exhibit 1 shows, the risk-adjusted returns of a 50-50 hedged and unhedged exposure to the MSCI Japan Index were stronger than a hedged exposure over both 3- and 5-year horizons, even though the yen broadly weakened over this timeframe. In other words, hedging outcomes may be heavily dependent on an investor’s chosen entry and exit points.

Hedging may make sense for investors with high-conviction currency or tactical views, or underexposure to U.S. Dollar-denominated assets. Investors with a strong belief that the U.S. Dollar will rise may want to replace foreign currencies with the U.S. Dollar. The same may be true for investors who have identified a need for more U.S. Dollar-denominated assets. In many cases, however, investors may have limited conviction in their currency views and a “home country bias” in their investments. For those investors, leaving the Euro, Yen or other foreign currency exposure within an international equity investment potentially adds to portfolio diversification.

Hedging may not have much effect on long-term returns. Unlike the short or medium term, and as distinct from tactical and opportunistic currency hedging strategies, hedged and unhedged equity investments have often delivered comparable long-run investment returns. This is consistent with the view that Developed Market currencies’ long-term expected returns are not significant after accounting for local interest rates. For instance, the MSCI EAFE Index, a benchmark of developed-world equities, has returned an annualized 8.3 percent since 1992, versus 7.3 percent for the MSCI EAFE USD Hedged Index.

In the past, the decision to invest internationally has had a greater impact on portfolios than the decision to hedge. Historically, with a few exceptions, both the hedged and unhedged versions of the EAFE Index typically outperformed (and underperformed) the S&P 500 Index in the same years. Each index also exhibited similar correlations to the S&P 500. As those observations suggest, the decision to go international in the first place has usually been more important than hedging considerations.

Steve Sachs is director of ETF Capital Markets and Candice Tse is senior market strategist, Strategic Advisory Solutions, at Goldman Sachs Asset Management.