The descendants of oil tycoon J. Paul Getty have one. So do Microsoft Corp. founder Bill Gates, Fidelity Investments Chief Executive Officer Abby Johnson and Hong Kong telecommunications tycoon Li Ka-Shing. They are family offices, the loosely regulated, privately owned companies that manage vast amounts of money for wealthy clans. They’re also among the most secretive firms in the world, and by all accounts they are expanding rapidly. Ask any expert on family offices to define them and the likely response will be: “If you’ve seen one family office, you’ve seen one family office.” Like families themselves, they vary widely.

1. What do family offices do?

They’re firms that serve a single family that has so much wealth that family members require their own money managers, accountants, estate planners, lawyers and other specialists to manage it all. Families usually need at least $500 million to set up a full-service office with an investment staff. Many employ dozens of professionals to pick investments, file taxes, pay the bills, oversee philanthropic missions and manage assets like yachts and vacation homes. Multi-family offices, which serve more than one family, are accessible at lower levels of wealth.

2. Who has them?

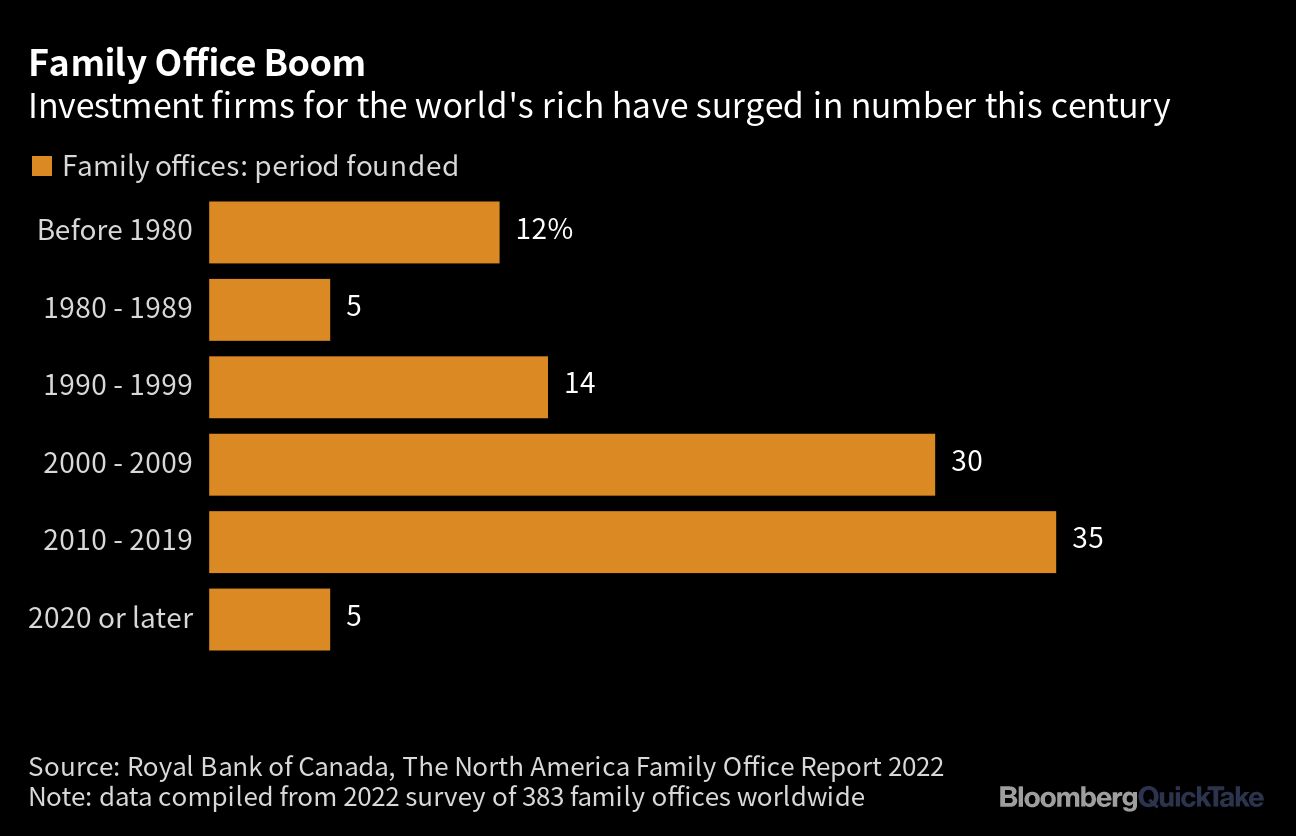

Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller set up one of the earliest modern versions in the late 1800s, and they’ve traditionally been used by the business magnates behind major companies such as Walmart, Johnson & Johnson, Cargill and Kering. As the number of mega-millionaires and billionaires has exploded, the use of family offices has spread to Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, private equity stars, Russian oligarchs, Middle Eastern oil families and newly minted tycoons in Asia. There were more than 10,000 single-family offices globally as of 2022, most of which were started within the last 15 years, according to EY.

3. How have they evolved?

They’re becoming more professional, with the largest offices operating like sophisticated investment firms. They strike out solo, or team up to buy and sell businesses, finance startups and acquire real estate. That way a family can exert tighter control over its money, cherry pick investments, minimize fees and even give the kids a board seat. Financial firms are feeling the pressure, and looking to woo family offices as clients and invest alongside them.

4. How much money do they manage?

A 2019 estimate by researcher Campden Wealth put the figure at almost $6 trillion globally — larger than the entire hedge fund industry. But it’s hard to say for sure. Families tightly guard the extent of their wealth and very few public records are available to track their assets. Single-family offices are generally exempt from registering as investment advisers with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, and therefore don’t have to disclose their owners, executives or how much money they manage. Financial centers including Singapore, Hong Kong and Dubai allow them substantial freedom and secrecy, too, and have launched initiatives to attract them to their jurisdictions. Many family offices chose obscure names to operate out of the public eye. Alphabet Inc. co-founder Sergey Brin’s family office, Bayshore Global Management, gets its name from the location of the search engine’s headquarters. Charles and David Koch named theirs after the year that their grandfather emigrated to America: 1888.

5. Who oversees them?

No one, really. Family offices are typically exempt from the reporting regulations that institutional firms face. The sudden demise in 2021 of Archegos Capital Management — a hedge fund by nature but a family office in name — resulted in US lawmakers unsuccessfully seeking to impose more transparency on them. That investment company, run by Bill Hwang, imploded after taking highly leveraged, multibillion-dollar bets on US-listed stocks. Those in favor of more rules argued that the relatively loose oversight of family offices made it easier for Hwang to build such enormous and risky positions without ringing alarm bells. Government authorities do, however, take a keen interest in the outcome of estate and tax planning. After all, just as much money can be made through savvy planning for what happens when a patriarch or matriarch dies as choosing the right hedge fund while they’re still alive. Charitable giving and accompanying tax deductions also come under the taxman’s purview.

6. What else can family offices do?

Almost anything. They can manage historical archives, art collections and personal staff, such as chefs or nannies. They can oversee family members’ travel and vacation plans, privacy and security. Cybersecurity has become just as important as physical safety — think of the racy selfies taken by Amazon.com Inc. founder Jeff Bezos that became tabloid fodder. Family offices can also help secure the best advice for getting offspring into selective US colleges.

7. Who works for them?

They attract talent from big banks, asset managers, private equity firms and endowments. For example, George Soros’s family office hired Dawn Fitzpatrick, who led the O’Connor hedge fund unit at UBS Group AG’s money-management arm, as its chief investment officer in 2017. After running Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s investment bank, Gregg Lemkau in 2021 joined an investment firm that grew out of the family office of Michael Dell, founder of Dell Technologies Inc. Top business schools in the US, including those at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Chicago, have courses tailored to producing professionals that cater to family-office needs.

8. What are multi-family offices?

Rather than serving just one family’s needs, they cater to multiple wealthy individuals or families who lack the money, expertise or desire to form their own offices. Because they provide advice on more than one family’s money, they are typically subject to financial services regulations. In the US, for example, they have to file disclosures with the SEC, just like hedge funds or private equity firms.

--With assistance from Simone Foxman and Margaret Collins.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.