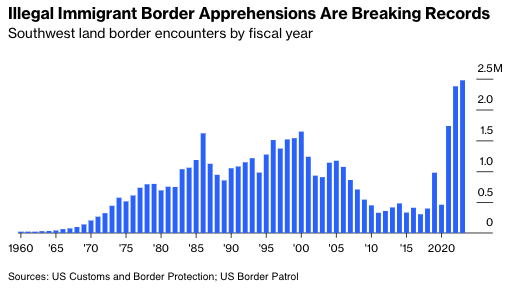

The number of people who are apprehended by U.S. Border Patrol agents or voluntarily surrender to them at or near the border with Mexico has skyrocketed recently, setting records in each of the past three fiscal years—and exceeding last year’s numbers in each of the first four months of the fiscal year that started in October.

This is usually interpreted to mean that illegal immigration is also setting records, but that’s probably not the case.

The problem with the statistics on what the Border Patrol’s parent agency, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, now calls Southwest land border encounters is that they leave out people who successfully evade the agency’s agents. In past decades, these were the majority of illegal border crossers. “Estimates are that only one out of three coming into our country are actually caught,” President Jimmy Carter said in 1977. More precise—albeit still pretty uncertain—Department of Homeland Security estimates of the Southwest border apprehension rate in the 2000s range from 33% (in 2003) to 43% (in 2000 and 2009).

In recent years, the apprehension rate has been much higher than that. According to the most recent estimate by DHS (Customs and Border Protection’s parent department), it was 81% in the 2021 fiscal year. Going by monthly CBP “got away” estimates compiled by the Cato Institute’s David J. Bier, the apprehension rate was 79% in both the 2022 and 2023 fiscal years, and 92% in the first four months of the 2024 fiscal year. That rate has risen partly because the US-Mexico border is more tightly controlled than it used to be, with more Border Patrol agents, taller walls and fences and more extensive and advanced surveillance technology. But mainly it’s just that most of the people crossing the border illegally don’t want to sneak past the Border Patrol. Instead, they intend to turn themselves in and apply for asylum.

This wave of asylum applicants truly is unprecedented, overwhelming the U.S. asylum court system and swamping cities with newcomers in need of shelter. My point here isn’t that everything is hunky-dory. But estimates of how many illegal border crossers don’t encounter U.S. agents are an essential piece of the immigration picture, and they haven’t received nearly enough attention in the media and in political debate. So I’m going to give them some.

To start, here’s the—shocking—picture painted by the CBP’s Southwest land border encounters data and equivalent earlier statistics on “illegal alien apprehensions” along the border published by the Border Patrol.

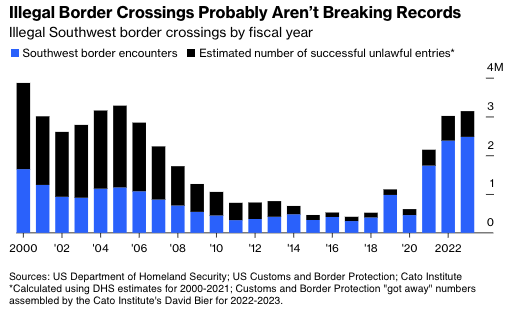

But again, in past decades far more people probably crossed the border illegally without getting caught. To estimate how many, DHS has used a statistical model based on surveys of recently turned-back border crossers conducted by El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, a Mexican government research center based in Tijuana, and some assumptions about their subsequent behavior. Doubts about the reliability of this model have been growing as the population of border crossers changes, and a pandemic-caused halt to surveys in 2020 and 2021 led DHS to skip making a model-based estimate for the 2021 fiscal year in its most recent Border Security Metrics Report. At the same time, though, increased electronic surveillance and more consistent standards have resulted in greatly improved CBP got-away reporting, which the DHS is increasingly relying on to produce apprehension-rate estimates.

Here’s what actual Southwest border crossings look like if you factor in model-based DHS apprehension estimates for 2000 through 2013, an average of the model-based and got-away-based estimates that DHS calls its “working estimate apprehension rate” for 2014-2020, the got-away-based rate reported by DHS for the 2021 fiscal year, and 2022 and 2023 got-away numbers released by the CBP in speeches, testimony and leaks to journalists.

The trajectory over the past decade doesn’t change much, but the comparison with the early 2000s does. There appear to have been fewer illegal border crossings in 2023 than in 2000, 2004 and 2005.

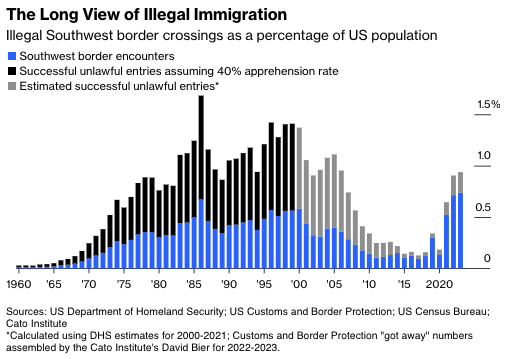

What about before 2000? As indicated by President Carter’s 1977 remarks, apprehension rates were probably similar to or lower than those of the 2000s. To provide a long-run view, I’ve (generously) assumed a 40% apprehension rate from 1960 through 1999, and expressed the inflows as a percentage of US population.

By this measure, illegal crossings of the Southwest border were lower in 2023 than in most of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. That doesn’t necessarily mean illegal immigration was lower, as individuals can show up multiple times in these statistics, and in past decades many Mexicans repeatedly crossed and recrossed the border illegally as work opportunities in the U.S. waxed and waned or simply returned home to visit family. Then again, from March 21, 2020, to May 11, 2023, as the emergency Covid-19 health order known as Title 42 led the CBP to turn back even asylum-seekers, many tried repeatedly—and were counted multiple times in the border encounter statistics.

These statistics also don’t count smugglers and others who cross the Southwest border but turn back, of whom there were an estimated 174,320 in the 2021 fiscal year; those who enter the U.S. illegally at places other than the Mexican border, whose numbers are usually small outside of exceptional events like the 1980 Mariel boatlift; or the hundreds of thousands of legal visitors who overstay their visas every year. But overall, the actual rise and fall and rise of illegal immigration to the U.S. over the past six-plus decades has probably followed a trajectory roughly similar to the one depicted above.

One aspect of that trajectory that doesn’t seem to be widely understood is that illegal immigration rates were at their lowest in half a century in the 2010s. In fact, they were probably negative on net, with the Pew Research Center estimating based on Census and other data that the U.S. unauthorized immigrant population fell from a record 12.2 million in 2007 to 10.2 million in 2019.

Illegal Southwest border crossings began to rise again during Donald Trump’s presidency, with the estimated number more than doubling from the 2016 to 2019 fiscal years before falling with the arrival of Covid-19. They’ve nearly tripled from that 2019 total since, and the most recent estimate I’ve seen of the unauthorized immigrant population, from the Center for Immigration Studies, puts it at 12.8 million as of October.

As already noted, it’s a much different sort of illegal immigration than that of the 1980s to 2000s. Rather than mostly Mexicans trying to get past border agents, it’s people from all over the world turning themselves in and hoping they’ll be allowed to stay. “A lot of them do have genuine asylum claims,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy director of the American Immigration Council, “but there are also people who arrive at the border never having heard of asylum but thinking the U.S. has open border laws.” He added, “We don’t have a functioning system that exists right now to distinguish who is who.”

Whether this is better or worse than the illegal immigration that prevailed from the 1980s to 2000s is a question I’m not going to attempt to answer here. But I’m at least pretty sure it’s not any larger in scale.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business, economics and other topics involving charts. A former editorial director of the Harvard Business Review, he is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.