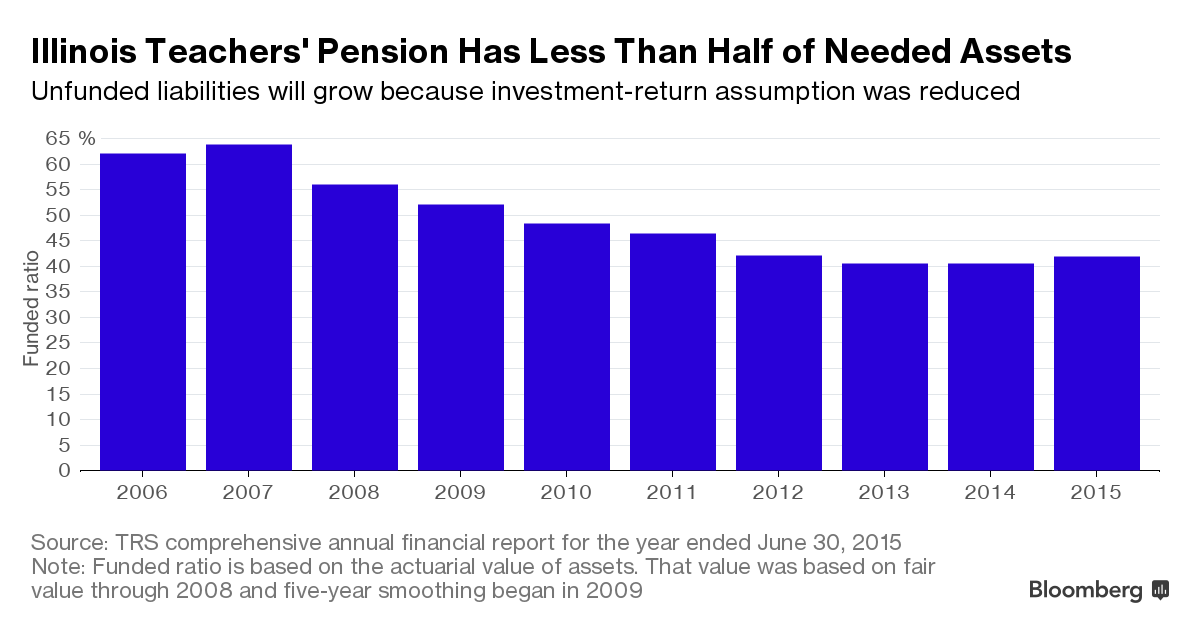

Illinois’s lackluster investment gains are making its most notorious problem -- pension debt -- even worse.

The state with the least-funded retirement system in the U.S. may see next year’s contributions jump by nearly half a billion dollars after its largest pension, the Teachers’ Retirement System, reduced the assumed rate of return on its portfolio. Because states count on such earnings to cover benefits checks, Moody’s Investors Service said the change added $7.4 billion to Illinois’s debt to the fund, a tab that it will have to chip away at year by year.

“There are no easy answers or financial or accounting tricks to stabilizing the state’s pension systems or the state’s finances,” said Laurence Msall, the president of the Civic Federation, a Chicago-based non-profit that tracks Illinois’s budget. “Pension funds have been allowed for decades to be dramatically underfunded and now -- at a time when market returns are difficult for the fund -- they need more and more contributions just in order to not lose ground from their already precarious financial position.”

The Land of Lincoln isn’t alone. Public pensions’ returns have dropped as central banks hold down interest rates, pushing bond yields to record lows, and global stock markets have been besieged by volatility. The under-performance has caused funds nationwide, including those in New York, Texas and Oregon, to roll back the returns actuaries use to determine how much governments need to save meet obligations to retirees.

In Illinois, the lowest-rated state, efforts to shore up its employee pensions have fallen victim to political gridlock. With the Democrat-led legislature and Republican Governor Bruce Rauner only able to agree on a stopgap budget, Illinois is on track to end the fiscal year $7.8 billion in the red, according to the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability.

It’s been more than 16 months since the Illinois Supreme Court threw out a pension restructuring that was projected to save $145 billion over three decades. The now-defunct plan cut benefits, a violation of the state constitution, according to the justices. Rauner and legislators haven’t been able to enact a new overhaul.

After posting a return of 0.1 percent in the year through June, the teachers fund decided late last month to cut the assumed rate of return to 7 percent from 7.5 percent, a step that will “significantly” affect how much Illinois will owe in the year that starts July 1, according to the retirement plan. While the magnitude hasn’t been determined yet, if the lower figure had been used for the most recent actuarial evaluation Illinois would have had to pay another $421 million this year, according to the fund’s actuaries.

Even with the short-term hit to the budget, the accounting change is a positive for Illinois by prodding it to put more into the cash-strapped fund, said Tom Aaron, a senior analyst at Moody’s.

“It’s reducing risk,” Aaron said. “It leads to better funding.”

Financial markets haven’t been helping pensions catch up, given declines in the U.S. stock market in August and January and equity-price declines overseas.