The latest inflation report, showing that price increases slowed in October, suggests that the U.S. just might get the “immaculate disinflation” that everyone is hoping for: Inflation will fall to its pre-pandemic levels and remain there, and the U.S. will avoid a recession. Allow me to make the pessimist’s case that we are not out of the woods yet.

I acknowledge that the sunnier view has a lot going for it. Optimism comes not only from the decline in actual inflation, but also from the decline in expectations of future inflation. Take a closer look, however, and it’s clear that some measures of expectations have not improved that much even as inflation has fallen. That means the situation is unstable and inflation could go back up again.

It is not enough for inflation to hit the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%. For a stable economy, inflation needs to be low and predictable going forward—just as it was pre-pandemic.

In many ways, the predictability of inflation is just as important as its level. When prices are unpredictable, they act as a kind of tax on consumers. An asset that offers variable returns is worth less, all else being equal, than an asset that offers fixed returns, because the predictability of knowing what your money is worth has tremendous value.

The uncertainty around inflation means a dollar is less valuable because you don’t know how much groceries will cost, or how far you can stretch your paycheck week to week. More uncertainty also increases interest rates on longer term bonds, because investors and lenders need to be compensated for the extra risk they take on.

One of the dirty little secrets of the economics profession, however, is that we have no good model for predicting inflation. The best we have—and the best way to measure this uncertainty—is expectations of inflation.

Expectations are important because they can be self-fulfilling and they help determine wage and price increases, investment plans, and asset prices. Expectations also explain why the Fed sets an inflation target: If everyone expects 2% inflation next year, then there’s a good chance that’s what we’ll get. So the Fed looks at expectations carefully, often noting that they are “well anchored”—that is, impervious to current data about actual inflation.

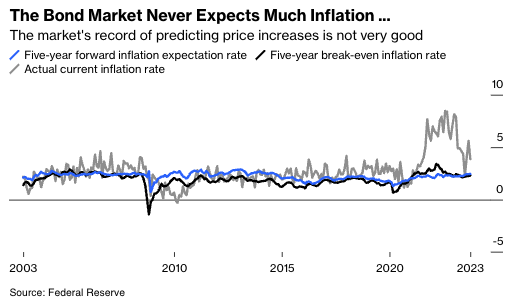

Expectation measurements can come from the bond market. The most popular are from bond derivatives and break-evens—that is, the difference between nominal and inflation-indexed bond yields. Both of these measures are expectations of what inflation will be several years from now. They have been fairly stable even as inflation rose, indicating that the market expected transitory inflation all along.

This measurement of expectations probably bolstered the Fed’s confidence that it was on the right track. If expectations suddenly increased, odds are there would be another rate increase. Of course bond markets often get things wrong, and break-evens reflect some quirks in the bond market that have nothing to do with inflation. And in fact the bond market has a terrible track record predicting inflation. So if the Fed cites bond-market expectations, it should not give anyone much comfort.

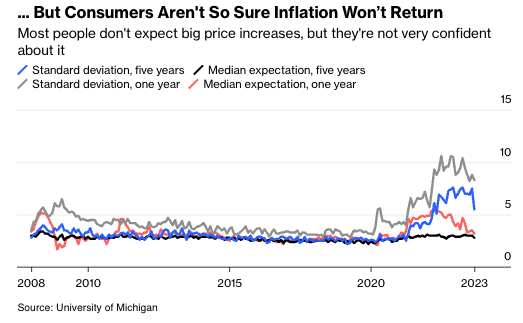

But there is another metric: household surveys. And if you look at median expectations of inflation a year or five years from now, both from the surveys of consumers from the University of Michigan and from the New York Fed, consumers are also expecting inflation to fall in the next year. Even when inflation was high last year, they consistently expected low inflation in the next five years.

Again, this is good news for the Fed and the chances of a soft landing. But here is where my pessimism creeps in: Confidence in those expectations is gone. Both surveys indicate consumers are much more uncertain about what inflation will be in the coming years, compared to what they thought in 2020. The figure below is the median inflation expectation in one and five years, and the standard deviation of those estimates among survey participants.

The standard deviation reflects the range of estimates. It shot up in 2021, and (despite a decline last month) is still elevated. The New York Fed’s survey has a similar finding. This suggests much less consensus and certainty around future prices. It helps explain why consumers still complain about inflation and have a dim economic outlook.

The uncertainty makes their dollar worth less, in risk terms. It also suggests that, even if inflation continues to fall, it is not as stable as it was before 2020. When people are not confident in their expectations, it does not take much for fear of inflation to return. An oil price shock, a single bad inflation report, even high turkey prices—any of them could cause people to lose confidence in the economy.

Before the pandemic, a generation of Americans had no experience at all with inflation, while for millions of others it was a distant memory. That translated into low inflation expectations—and high confidence in those expectations, which in turn contributed to price stability. A few years of rising prices have shattered that confidence. It could take years of luck, and good monetary policy, to get it back.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.