If stock market volatility and low interest rates make being a financial advisor tough today, consider what it was like in the 1970s. At that time, as inflation took hold and economic growth stagnated-the toxic confluence of conditions that eventually came to be known as "stagflation"-hard assets such as real estate thrived as financial assets such as stocks and bonds took a beating.

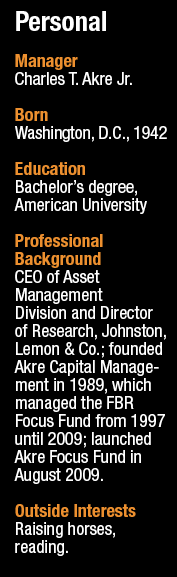

Back then, Chuck Akre was a young stockbroker working for a regional brokerage firm in Washington, D.C. He remembers clients calling and asking if perhaps they might be better off pulling their money out of stocks and putting it in real estate, in artwork or even under the mattress-anywhere but financial assets. "Just about everything was losing value, and people weren't happy about it," says the 69-year-old founder and manager of the three-year-old Akre Focus Fund.

But Akre found a way to play defense. The self-taught investor, who graduated from American University in 1968 with a degree in English literature, found that the stocks faring better were those of companies that could stay competitive by raising prices to keep pace with inflation. In a slow economic environment, he reasoned, those stocks could endure if they had a market leadership position, faced no competition or boasted some other sustainable advantage.

But Akre found a way to play defense. The self-taught investor, who graduated from American University in 1968 with a degree in English literature, found that the stocks faring better were those of companies that could stay competitive by raising prices to keep pace with inflation. In a slow economic environment, he reasoned, those stocks could endure if they had a market leadership position, faced no competition or boasted some other sustainable advantage.

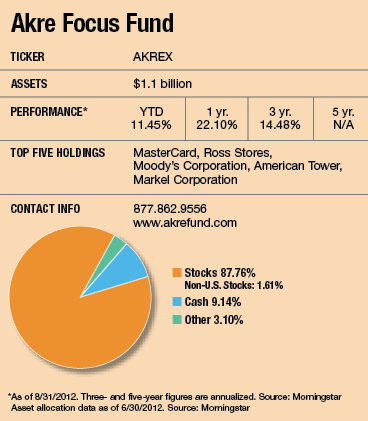

The names of such companies have changed over the last 40 years, but the major theme running through the Akre Focus Fund's concentrated 25-stock portfolio is the same: The companies must enjoy an ongoing advantage allowing them to maintain pricing power amid slow economic growth. One holding, Apple, has been able to do this because of its dominant market niche. Others, such as Dollar Tree and Ross Stores, can lower the prices on their merchandise to draw cash-strapped consumers.

It will be critical to maintain pricing power over the next several years, Akre believes, and he says a familiar economic environment could well re-emerge as he approaches his 70s.

"We consider the possible outcomes for the fiscal crisis which exists in the U.S. today," he wrote in his second-quarter commentary to shareholders. "We believe a likely scenario is an experience not unlike the 1970s, which was termed "stagflation," and was characterized by low growth and rapidly rising interest and inflation rates."

With Congress unwilling to cut spending, the national debt will continue to accumulate. "The government will keep printing money, which will devalue our currency. In all likelihood, inflation will rise at a significant rate. The last time anything like that happened was the 1970s."

At the same time, economic growth will remain constrained by consumers who have more limited access to credit and have reached the end of their spending rope. "The official unemployment rate is just over 8%, but including those who have given up looking for work or who are working fewer hours raises that figure to the midteens," he says. "In an economy that's driven by consumer demand, the ability to increase spending just isn't there."

In such an environment, he says, it's important to look for "compounding machines"-companies likely to produce strong long-term returns on equity. These must be reasonably priced; he will only buy them if they sell at no more than 15 times free cash flow.

Akre prefers that managers reinvest cash to help grow their businesses rather than distribute it to shareholders as dividends. Executive compensation must not make excessive use of stock options or other reward systems that dilute the financial interests of existing shareholders. And the companies must keep their debt at reasonable levels to avoid the ravages of possible rising interest rates.