Confirmed cases of Covid-19 and hospitalizations from the disease have been plummeting for weeks in the U.S. and elsewhere in the Northern Hemisphere. Deaths also are in decline. So it seems the long-dreaded fall-winter wave of the pandemic, which turned out to be just about as terrible as feared (with the exception that it wasn’t accompanied by much of any seasonal influenza), has finally crested.

In more good news, some quite effective Covid vaccines are now available, and after a fitful start, the U.S. effort to inject them into people’s arms is steadily gaining speed. Four times as many people are now receiving first vaccine doses each day as are being infected with the disease, according to the infections estimates of both data scientist Youyang Gu’s covid19-projections.com and the covidestim.org model assembled by researchers at the Harvard and Yale schools of public health.

So is that it? Is the worst of this pandemic behind us, or are there more big waves to come?

By this point the most sensible answer to such questions about Covid-19 is probably ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. But a few key variables seem most likely to determine what happens next, and running through them may shed at least a little light on the path ahead.

New Variants

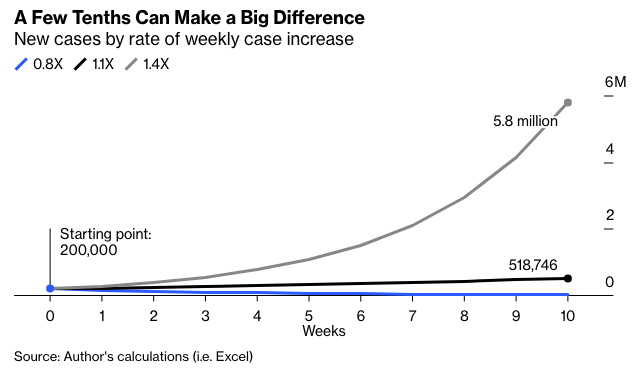

The B.1.1.7 variant that has become predominant in the U.K. and is expected to take over soon in the U.S. has been estimated to be 30% to 70% more transmissible than the version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus we have come to know and heartily dislike. Because of the magic of exponential growth, this can translate into a greater than 30%-to-70% increase in the number of cases in just a few weeks.

Here’s an illustration, using the simple exercise of starting with the number 200,000 (about how many new Covid-19 infections there are each day in the U.S.) and multiplying by 0.8 (about the rate at which Covid-19 infections have been going down in recent weeks), 1.1 (37.5% more than 0.8) and 1.4 (75% more than 0.8) for each of 10 periods that I’ll call weeks.

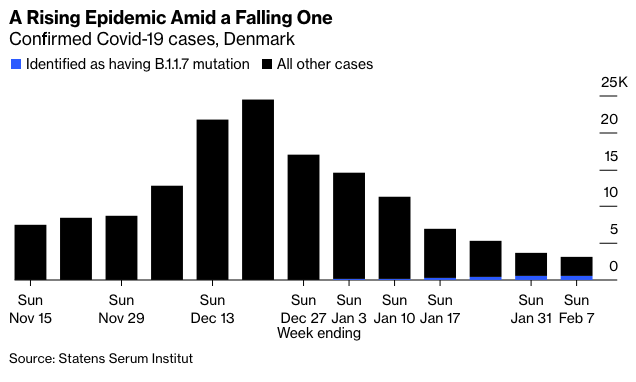

What seems like only a moderately higher growth rate can bring many, many more cases in short order. In the real world, as in the susceptible-exposed-infectious-recovered (SEIR) models that epidemiologists use, the growth rate does at least slow over time as people become immune and change their behavior to avoid the disease. In Denmark, which is doing the world’s best job of testing for B.1.1.7 and other mutations — and where schools, restaurants, bars and non-essential shops have been closed since Christmas — B.1.1.7 cases are growing modestly amid a collapse in other Covid-19 cases.