The pandemic was so bad for working women, especially mothers, that it was known in some quarters as the “she-cession.” But the recovery—and can we please not call it the “she-covery”—has been pretty good for them.

In the last few years, after decades of stagnation, women have made progress at closing both the labor gap and the wage gap. The jobs market has undergone some big changes that favor women — though they also make women more vulnerable if it turns.

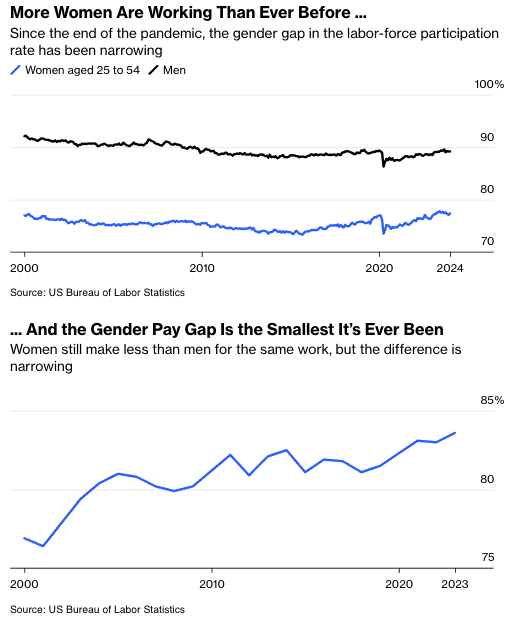

For most of the industrial era, women’s work was an afterthought. Not only did women face discrimination in the workplace, but there was an expectation they’d stop work once they had a family. When social norms and technology changed, however, so did women’s leverage in the labor force. Women made progress through the second half of the 20th century: By the year 2000, more than 75% of women between the age of 25 and 54 were working, up from the 40s in the 1960s, while the wage gap (how much a woman makes for every dollar a man makes) went from 62.3 cents in 1979 to about 77 cents.

Then progress slowed. The wage gap remained stuck in the low 80s, and the prime-age labor participation rate in the mid-70s.

Post-pandemic, however, things are starting to change. Women’s labor force participation has never been higher, and the wage gap has even narrowed a bit. Technology has altered the options for work, enabling more women to have the flexibility they need.

Whether the gender wage gap even exists has become a point of controversy. It is now 83.8, the smallest on record. After accounting for hours worked, and what fields women choose to study and join — the market values engineers more than social workers—it is smaller still: in the 90s, or a gap of less than 10%.

That’s progress, but: A woman earning 10% less than a man for the same work is hardly something to celebrate. And the gap widens over time, growing from near parity when women graduate from college to when they enter middle age. It is also larger among the college- educated.

What accounts for the gap? Research by Nobel economics laureate Claudia Goldin estimates that it is largely due to the fact that women often need more flexibility at work once they have children. For jobs that pay very well, employers want workers who can be available most hours of the day.

Flexibility, like health insurance or paid vacation, is a workplace benefit. And like other benefits, it imposes a cost on employers. This helps explain why there is still a wage gap even between male and female OBGYNs, for example: As it turns out, male doctors are more likely to be able to deliver babies in the middle of the night, and they get paid for their willingness to work those hours. In contrast, the pay gap is practically non-existent for pharmacists, where there is little return to working long or odd hours.

Even before the pandemic, the labor market was changing in ways that benefited women. Manufacturing jobs, which tend to require more strength and manual labor, were in decline, while so-called care jobs were rising. But the real game-changer may have been the increased popularity of remote work.

Remote work allows women to both work more hours and be more available to their families. And this flexibility is now easier and cheaper for employers to offer. That’s a big reason more women than ever are working, while male prime-age participation is just where it was pre-pandemic, despite a very strong job market. The option for flexibility will continue even as more people return to the office, because the technology has improved and the workplace norms have shifted. “Anxious overachievers” still exist, but do they really need to work an obscene amount of hours?

It is also worth noting that while more women are working, they are working fewer hours. Overall, according to ADP, Americans are working less, and the trend is being driven by women. This suggests the newfound flexibility may prove to be a double-edged sword. In a tight labor market such as this one, employers are happy to offer flexibility for free. But eventually the labor market will turn, and then being available and in the office could command a higher premium—and widen the pay gap.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.