You could almost feel the shockwave that JPMorgan Chase & Co. sent across Wall Street on Tuesday morning with its third-quarter earnings.

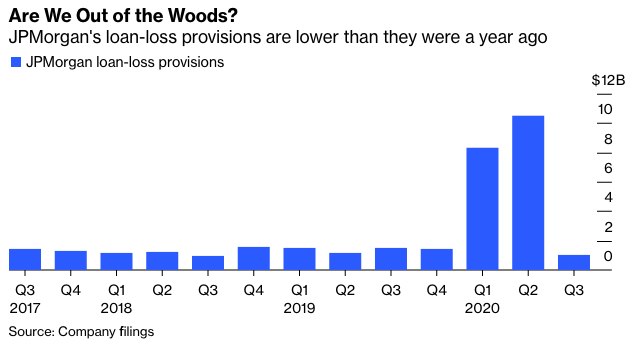

Investors have always scrutinized results from the biggest U.S. bank, which provide insights into all corners of the economy. But they’ve rarely been as critical as during the coronavirus crisis, which has put in stark relief the divide between small businesses and large corporations; between front-line workers and those in white-collar jobs; and between homeowners and those who rent. The message from JPMorgan until this point has been clear: We’re going to get through this but have reason to expect much more pain ahead. In July, the bank announced it had set aside a whopping $10.47 billion for credit losses, more than anyone predicted and up from $8.3 billion in the first quarter.

Analysts predicted that JPMorgan would earmark another $2.4 billion for potentially bad loans in the three months through September, a period defined by gridlock among Washington lawmakers over another round of fiscal aid as the Covid-19 pandemic flared up across the U.S.

Instead, it set aside just $611 million.

That figure is stunning. Not only was it far below analysts’ expectations, but it was down $903 million from a year earlier. The low provisions for credit losses make it seem “as if Covid-19 never happened,” said Octavio Marenzi, chief executive officer of consulting firm Opimas, and “strongly suggested that JPMorgan Chase had overestimated the impact of the epidemic on credit losses.” And JPMorgan doesn’t look like an outlier — Citigroup Inc. also set aside about $1.5 billion less for bad loans in the third quarter than analysts had expected.

Still, I would take a breath before declaring this an all clear for the U.S. economy.

For one, it was obvious that JPMorgan was being somewhat conservative with its past buildup in loan-loss reserves, using record-breaking trading revenue as cover while still beating overall expectations. “If the base case happens, we may be over-reserved. I hope the base case happens,” CEO Jamie Dimon told analysts in July. In total, JPMorgan has almost $34 billion reserved for credit losses.

The bank’s base case now is for a U.S. unemployment rate of 9.5% at the end of the year and 7.3% by the end of 2021, compared with estimates of 10.9% and 7.7%, respectively, as of July, when the jobless rate was in the double digits. Considering that the unemployment rate fell to 7.9% in September, JPMorgan is either being overly cautious yet again or expects the labor market gains to slow, if not reverse.

Chief Financial Officer Jennifer Piepszak addressed this tension multiple times during the bank’s conference calls. The reserve releases that contributed to lower-than-expected provisions for bad loans shouldn’t be seen as a sea change in the bank’s assumption about how the economy will perform, she said, though she indicated that JPMorgan doesn’t expect any significant increase in charge-offs until the second half of 2021. “The medium to longer term is still highly uncertain, in particular as it relates to future stimulus,” she said. “So we remain heavily weighted to our downside scenarios.”