Imagine an investment with stock-like returns and cash-like stability, or close to it. Many investors believe they have found such a thing. It’s called direct lending, and like countless investments before it that promised big profits with little risk, it’s probably too good to be true.

Direct lending refers to private loans made by investors to small and midsize companies, most of them owned by private equity funds. The private equity game calls for buying businesses with hefty amounts of debt to bolster returns, and banks traditionally supplied the financing. But a combination of surging demand for private equity investments and tighter bank lending standards after the 2008 financial crisis forced private equity funds to look elsewhere for capital.

Direct lending has filled the void in a big way. Nearly $1.5 trillion is invested in private debt globally, according to data provider Preqin Ltd., about half of which is direct lending. That number is up fivefold since 2010, and Preqin estimates investment will reach $2.2 trillion by 2027.

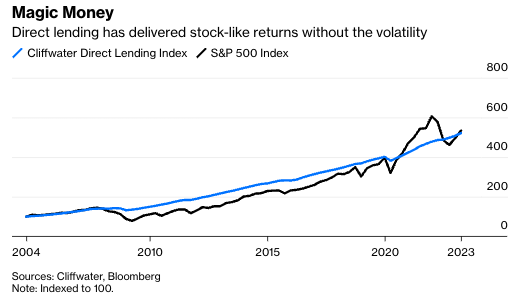

Performance results for direct lending are scarce because private loans are not publicly traded, but the available data explains why it’s so popular. The Cliffwater Direct Lending Index, a collection of more than 12,000 middle-market loans, shows a return of 9.3% a year since 2004, nearly matching the S&P 500 Index’s return of 9.5% during the same period.

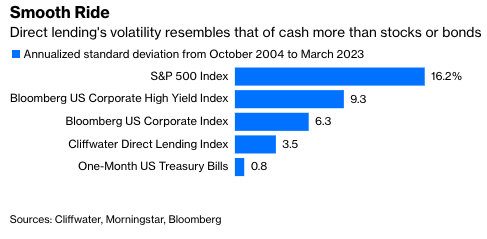

The astonishing part is that direct lending has kept pace with stocks while looking more like cash. The direct-lending index’s volatility, as measured by annualized standard deviation, has been 3.5% since inception, which is a lot closer to the volatility of Treasury bills (0.8%) than the S&P 500 (16.2%) over the same time. Think of a nearly uninterrupted upward sloping line, and that pretty much captures investors’ experience in direct lending.

There’s just one catch: Direct lending’s volatility is fantasy. Unlike publicly traded stocks, there’s no market spitting out prices for private loans. That judgment is left to operators of direct-lending funds, who have little incentive to acknowledge that their investments occasionally decline in value. So they mark their loans sparingly and almost never downward unless the declines are too obvious to ignore.

Those infrequent marks give private loans a veneer of stability. The direct-lending index was down in just six of 74 quarters since inception, compared with 19 for the S&P 500. Four of the six declines coincided with the 2008 financial crisis and Covid-19 selloff, and even then, they were very modest. Private loans would be at least two to three times more volatile if they traded publicly.

Direct lending’s muted volatility—and that of private investments more generally—is a wink and nod between fund managers and investors: The funds pretend that the loans have a stable value, and investors have good reason to play along. Those investors are predominantly pension funds, endowments and insurance companies with portfolio managers who are tasked with maximizing return and minimizing volatility. For that, direct lending is a dream, and the more of it they stuff into their portfolios, the better they look.

But pretending that direct lending is stable doesn’t make it so. Private debt has been blessed with ideal conditions, and that may be about to change. For much of the time since the financial crisis, money has been cheap and plentiful, which has made it easy for companies owned by private equity to service their debt and obtain new loans when needed. That debt has floating rates, however, and most of it is unhedged, which means that companies are paying a lot more in interest than they did a year ago. If interest rates move higher or just hang around current levels, many companies will have trouble paying their debts, handing losses to lenders.

It could be worse. If higher rates are coupled with a sluggish economy, businesses will suffer and private equity firms will be forced to write down the value of their portfolio companies, which will make it harder for those companies to refinance existing debt or obtain new loans. One can easily imagine a cascade of lower equity values that freeze companies out of debt markets and push them into bankruptcy. The volatility of private investments won’t seem so tame then, least of all direct lending.

Such a situation is top of mind for regulators and central bankers. The lifeline for direct lending—aside from the fact that equity holders would be wiped out first—is that the business of private investments is already too big to fail. Pensions and endowments routinely allocate a third or more of their portfolios to private assets, and private investments are increasingly in portfolios that banks and advisers manage for individuals. A shakeout in private markets would imperil charities, colleges and universities and the retirement of millions of Americans.

The ripples would be felt well beyond. There’s no way to invest the trillions of dollars in private assets without touching every part of the economy, and private equity has, from physician practices and pet stores and 30% of for-profit hospitals to newspapers and mobile homes and apartment buildings and prisons. At this point, policymakers can’t allow private equity to collapse without bringing the economy down with it.

For now, investors expect the private debt party to continue. BlackRock Inc. estimates that direct lending will return 10.4% a year over the next 10 years, the second-highest expected return of the 24 investments it tracks, only behind emerging-market stocks. But investors should wonder about the risk. Here’s a hint: There’s a reason banks tread lightly there.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.