“History never repeats itself, but it often rhymes.” -Mark Twain

We wrote recently about the huge valuation spread between the 100 most expensive stocks in the S&P 500 Index and the 100 cheapest stocks. All the academic studies we’ve seen show that cheap stocks outperform average and expensive securities despite the bright futures which the more expensive ones are assumed to have. Thanks to some great writing by Corrie Driebusch and Chris Whittall of the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), we have more evidence and an effective way to cross-check that analysis in a piece called “Popular Investments Are Ripe for a Fall.” Their well-written article is very germane to the current discussion and this is how they introduced the subject:

Investors are worried that some of this year’s most popular trades are vulnerable to a reversal.

Government bonds, dividend-paying stocks and emerging-market securities have been bid up in the global search for yield. In an unusually quiet market, any shift in sentiment could send investors who have piled into similar positions all heading to the exits at the same time. [i]

Our research showed that the cheapest stocks trade for 10.2 times after-tax-profits on Wall Street consensus estimates for 2017 versus over 50 times the profits of the 100 most expensive stocks in the index. It is also the biggest spread we could find since the tech bubble of the late 1990’s. In other words, the present reality rhymes with late 1999. We concluded from looking at the breakdown of the 100 cheapest stocks that financials dominated the lineup, with 33 entries, followed by numerous economically-sensitive industries like airlines (industrials), housing and retailers (consumer discretionary). This is very similar to the composition of the 100 cheapest P/E stocks at the beginning of 2000.

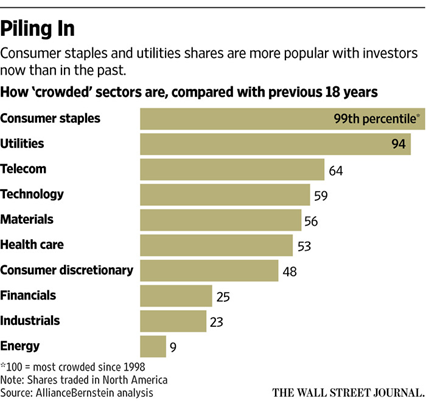

With kudos to the WSJ writers and the researchers at Alliance Bernstein, here is another picture of the same subject with more proof of our thesis going back to 1998.

From a historical perspective, what do you do with a chart like this as a long-duration stock picking organization? Initially, you start out by digging into these numbers to look for anomalies in the sectors which help to frame the crowded and lonely trades.

The consumer discretionary category is heavily skewed in the Alliance Bernstein chart by the inclusion of Amazon (AMZN) and Netflix (NFLX). Amazon trades at a capitalization equal to 1.58% and Netflix trades at .22% of the entire S&P 500 Index. They make up a whopping 15% of the consumer discretionary sector. At trailing P/E ratios of 192 and 325, respectively, they are distorting how out of favor the consumer discretionary category currently stands. The consumer discretionary sector trades at 19.7 times trailing earnings and imagine what it would be without Amazon and Netflix. We’ve shown recently that many consumer discretionary companies trade among the cheapest 100 stocks in the S&P 500 Index.

Since these companies (AMZN, NFLX) are traded and organized as technology companies, this is making consumer discretionary look very normally owned (48th percentile) and tech comes away not nearly the historical darling that we believe it is today (58th percentile). Since Amazon is getting almost all its profit from their AWS cloud business, it is easy for us to add their capitalization to the tech sector of the index. If you do this, it makes the current circumstance even more like 1999.

A quick reminder of what happened back in the late 1990’s. The technology and telecom sector investments went to the highest P/E multiples in history. The money poured into U.S. large-cap growth mutual funds and they in turn bought more of the tech/telecom bubble stocks and invested heavily in growth-oriented large-cap consumer staple shares. In other words, they “piled in” to trades which were the most crowded in the history of the U.S. stock market. Growth strategies completely swamped value disciplines.