The U.S. credit card industry might be in a battle on two fronts.

First, the charge-off rate among card issuers in the first quarter increased to the highest level in almost seven years. The figure is effectively a gauge of “bad debt” — it reflects the percentage of loans companies have concluded will never be repaid. As Bloomberg News’s Jenny Surane noted last month, executives like Capital One Financial Corp. CEO Richard Fairbank chalked that up to the length of this economic expansion causing some negative credit events during the financial crisis to disappear from credit bureau reports, essentially making risky borrowers look stronger.

This idea of consumer “grade inflation” is part of the zeitgeist at this point. Experian even posted a handy guide that details how long it takes for certain events to be removed from an individual’s report. It’s seven years for late payments or accounts that have to go into collection. Interestingly, the amount of seriously delinquent credit card payments reached an all-time low in the second and third quarters of 2016 — almost exactly seven years after the recession officially ended.

I wrote last month about how analysts from Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Moody’s Analytics were fretting about the true risk embedded in FICO credit scores from Fair Isaac Corp., and I concluded that it’s a signal to get smarter about lending. Indeed, that’s what companies appear to be doing: Discover CEO Roger Hochschild told Surane in an interview that “in general, we have been contracting credit policy at the margin and tightening” because of the length of the economic expansion.

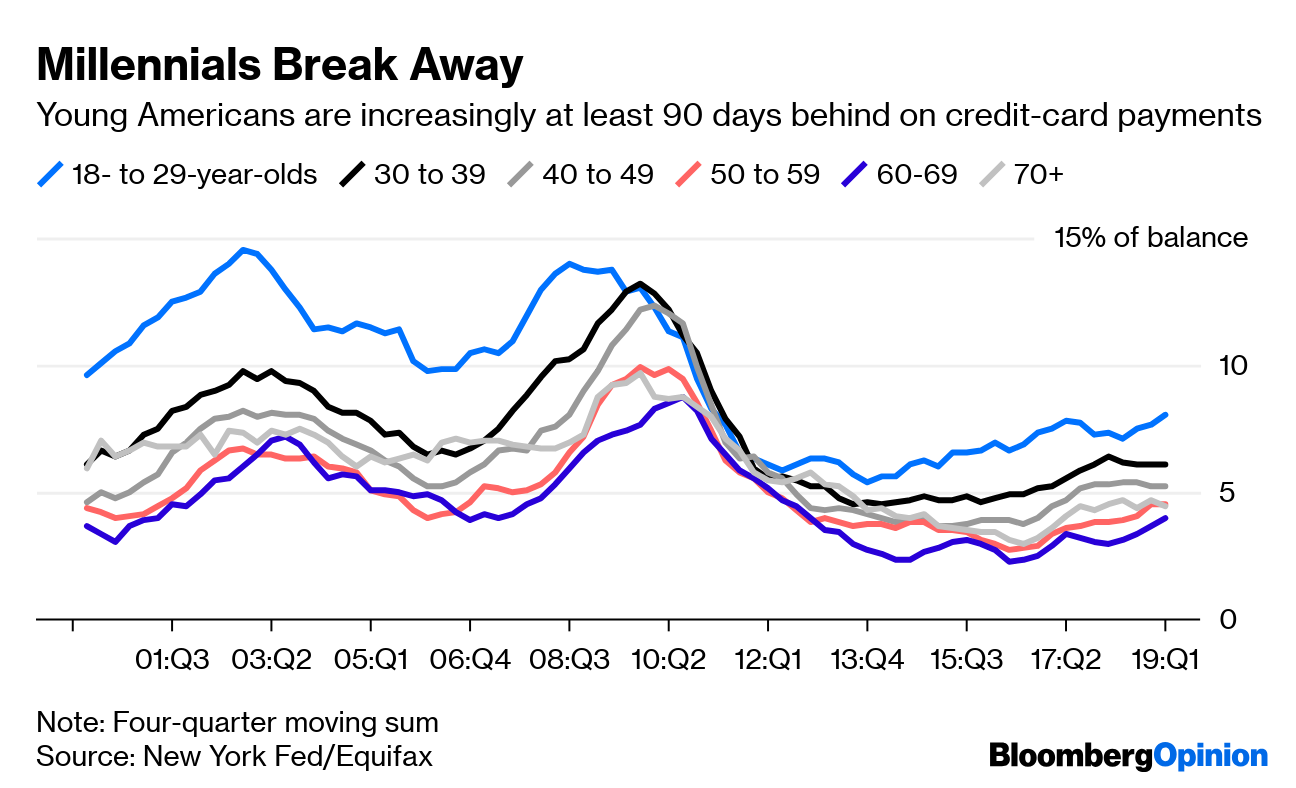

However, these murky credit reports can’t fully explain a second area of concern for card issuers. Some 8.05% of outstanding credit card debt among Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 was delinquent by at least 90 days, the highest level since early 2011, according to data released this week by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. That’s by far the highest share among age groups and up from 5.37% at the end of 2013. Obviously, the FICO scores for a large chunk of this group didn’t suffer during the downturn.

Andrew Haughwout, senior vice president at the New York Fed, somewhat played down the overall rise in late credit card payments, arguing that it reflects “an increase in younger borrowers entering” the market. He added in a statement that “these delinquency rates are increasing from historically low levels and remain below pre-financial-crisis levels.”

That may be true, but even if credit card delinquencies aren’t back at 2008-2009 levels, it seems increasingly likely that the industry has reached a turning point. If younger borrowers can’t make their payments now, whether because they’re saddled with other debts or their wages aren’t rising fast enough, how will they fare if the economy falters? Perhaps this uptick, concentrated among twenty-something voters, helped encourage Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Bernie Sanders to call for new legislation that caps credit card interest rates at 15%.

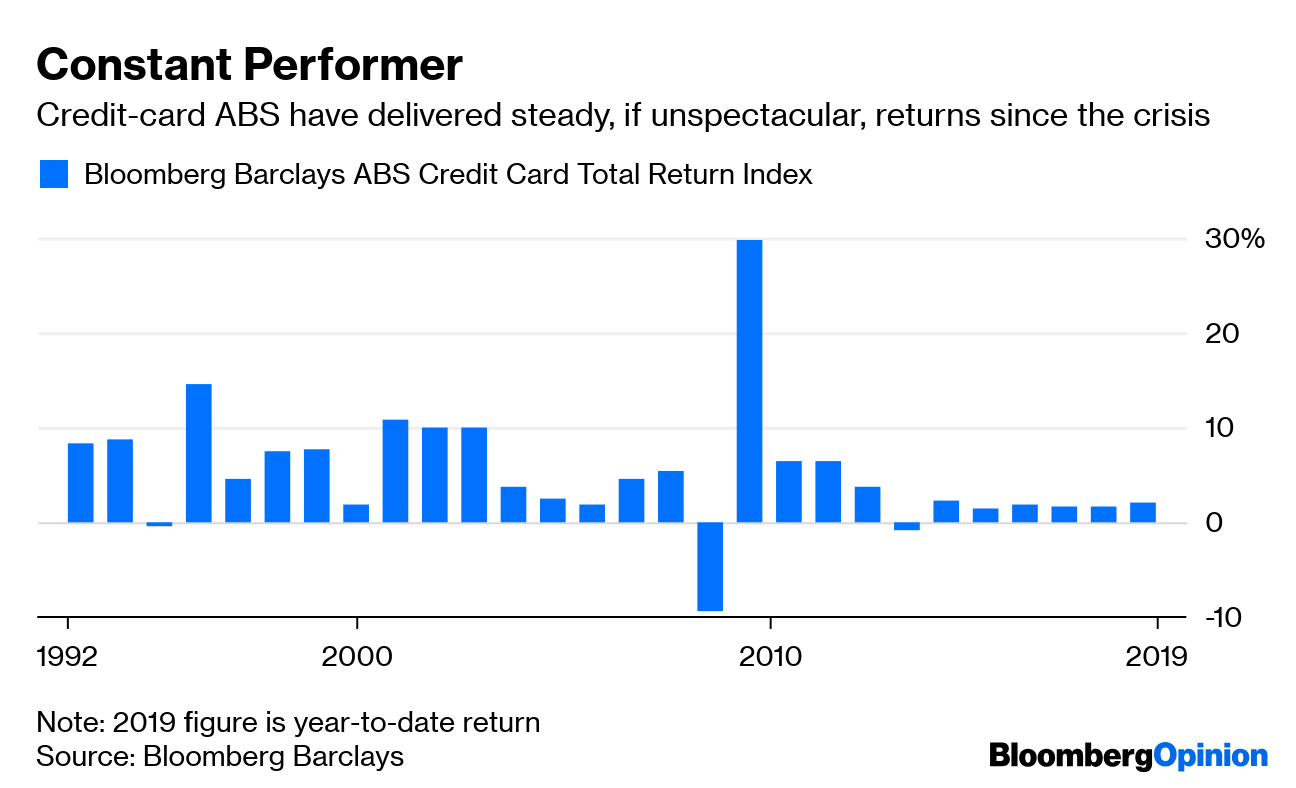

Meanwhile, investors in asset-backed securities tied to credit card receivables are having big paydays. An ICE Bank of America Merrill Lynch index of fixed-rate credit card ABS gained 1.26 percent in the first three months of 2019, its strongest quarter in three years. The floating-rate index returned 0.9 percent, the most since early 2010. Broadly, the Bloomberg Barclays index of credit card ABS has delivered a 5.2 percent annualized return since the end of 2008, better than the aggregate bond index’s 3.7 percent.