At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, people, jobs and economic activity moved outward from New York City into the suburbs, exurbs and points beyond. Since then, going by the jobs data, the region has been experiencing a different kind of shift—toward New Jersey.

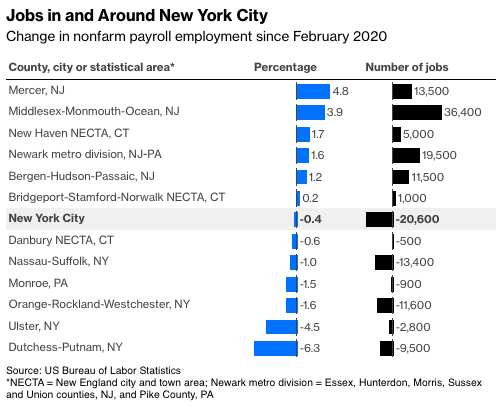

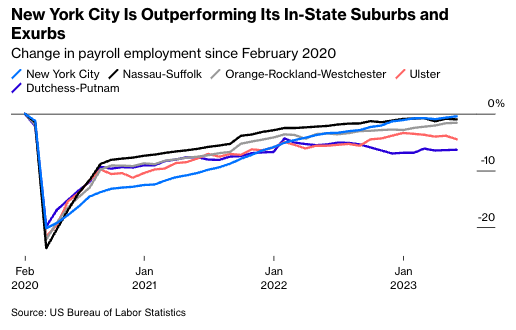

Nonfarm payroll employment was 8,000 higher in June in the New York-Newark-Jersey City metropolitan area than in February 2020 after adjusting for seasonality. That’s an increase of less than 0.1%—effectively no change—during a period when employment rose 2.5% nationwide. In New York City, employment is still down by 20,600, or 0.4%, so all the gains have been in the suburbs. But the suburbs in New York state appear to have done even worse than the city, meaning almost all the job growth has been in New Jersey.

I say “almost” because there is also one not very populous Pennsylvania county in the metro area, and because there’s been some job growth in New York’s Connecticut suburbs, which aren’t part of the metro area—the lines of which are determined every few years by the White House Office of Management and Budget based on commuting patterns and other criteria. The Connecticut suburbs, along with some outlying counties in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, are part of the broader New York-Newark combined statistical area, but the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t report jobs by combined area, and while it does report them for parts of New York metro and combined areas, it does not do so consistently enough to add up those parts to get the whole. (The BLS's Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, which is based on unemployment insurance data, does provide monthly estimates of employment by county, but they're not seasonally adjusted, and the most recent numbers available are from December.) So let’s look at the parts:

Mercer, Middlesex, Monmouth and Ocean counties in central New Jersey are booming, with job growth well above the national 2.5% pace (it’s an even-higher 5.4% in Philadelphia’s New Jersey suburbs, and 2.6% statewide), while northern New Jersey is adding jobs, albeit slowly. Same with the Connecticut regions along the Metro-North Railroad, although the number of jobs involved is pretty small. Meanwhile, New York City is getting close to recovering its pandemic job losses but isn’t quite there; Long Island is lagging the city; the suburban counties just to the north are lagging it even more—and the Hudson Valley exurbs north of that look as if they’re in a depression.

What’s weird about this is that the Hudson Valley is generally thought to have boomed during the pandemic. Ulster County, aka the Kingston metropolitan area, was the hottest real estate market in the country as of mid-2020, according to the National Association of Realtors, with the median sales price of a single-family house up 18% from a year earlier to $276,000. Home prices in the very scenic county—which includes parts of the Catskill Mountains and Shawangunk Ridge, the college town of New Paltz and world-famous Woodstock—kept rising after that, with the median hitting $398,800 in the second quarter of last year before dropping a bit since.

That employment didn’t keep pace with real estate prices is partly due to long-running trends in a region that used to have a lot of manufacturing jobs (many with IBM, which had big plants in Dutchess and Ulster counties) and doesn’t now. But it’s also because a real estate boom brought on by affluent second-home buyers and remote workers doesn’t necessarily bring much job growth and can even drive jobs away as it prices people out of the region. The jobs numbers cited here are as reported by employers, so I did wonder if there were a lot of new Hudson Valley residents whose employment was being counted elsewhere, but the (less-reliable) place-of-residence jobs estimates derived from a variety of sources show employment declines since before the pandemic in Dutchess, Putnam and Ulster counties even as they show modest increases in Orange, Nassau, Rockland, Suffolk and Westchester. Dutchess, Putnam and Ulster also returned to their pre-pandemic habit of losing residents to domestic migration from mid-2021 to mid-2022, according to the Census Bureau, after big inflows in 2020-2021.

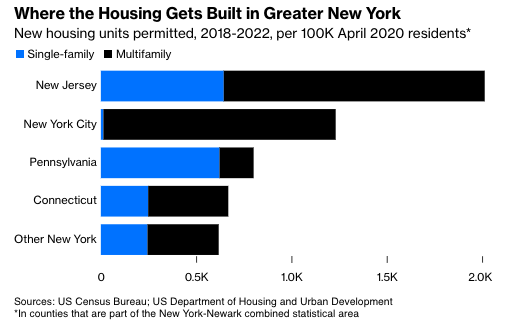

As for what’s driving the job growth in New Jersey, taxes may play a role. New Jersey’s 2022 state and local tax burden of 13.2%, as estimated by the Tax Foundation, is the fifth-highest in the country but is markedly lower than the 15.9% of No. 1 New York and 15.4% of No. 2 Connecticut. An even bigger contrast is new housing—over the past five years, New York City’s New Jersey suburbs and exurbs have built it at not too far off the national pace, relative to population, while the city and especially its other suburbs have trailed far behind.

One can’t say with certainty that New Jersey’s faster pace of housing construction caused its faster pace of job growth—it could be the other way around. But these patterns show up often enough around the country that it’s at least clear that building lots of new housing is compatible with stronger employment growth. In the slow-growth region that is Greater New York, it may be what is allowing New Jersey to stand out.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business, economics and other topics involving charts. A former editor and writer at the Harvard Business Review, Time and Fortune, he is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.