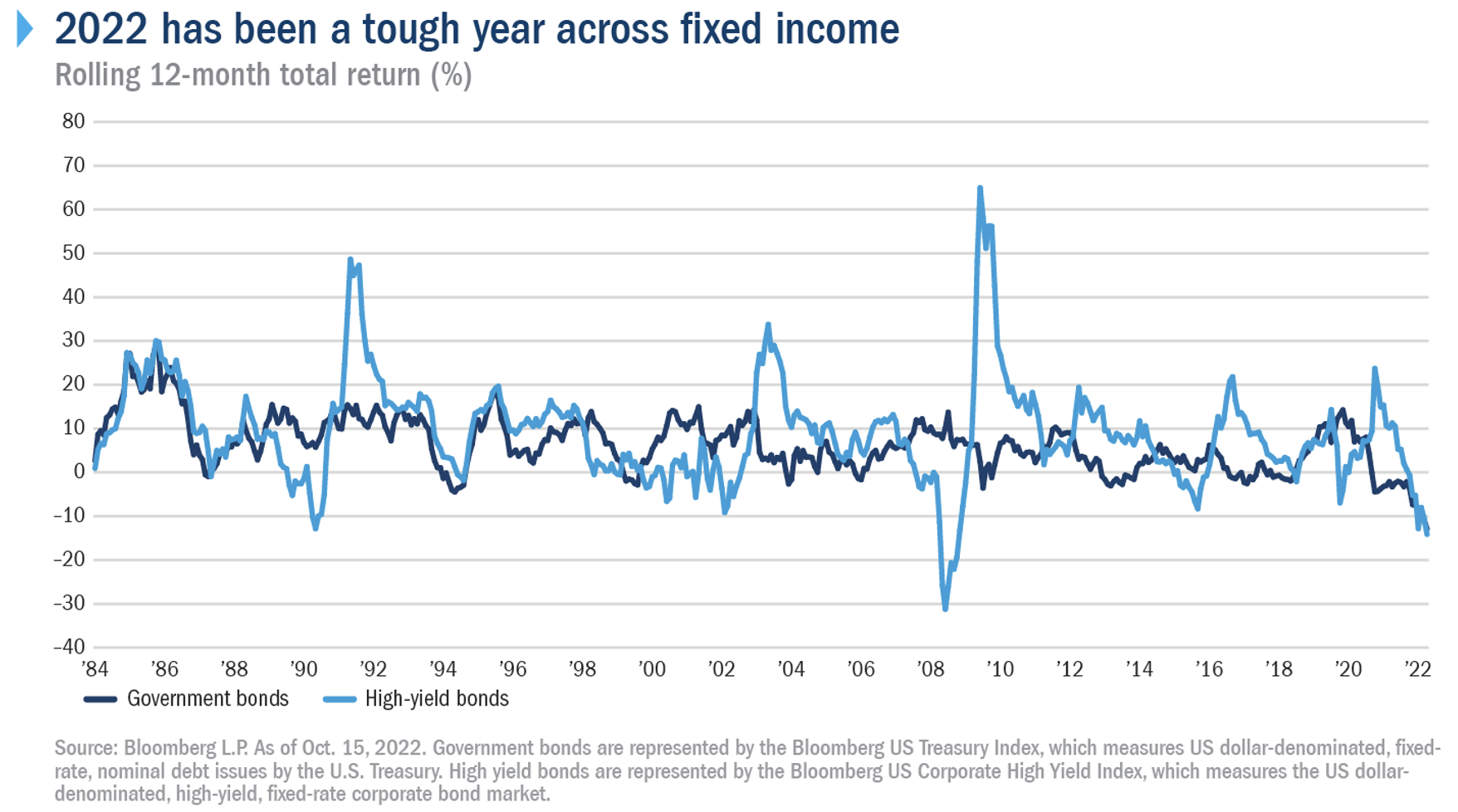

Global bond markets have been rattled in 2022 by central banks’ aggressive policy pivot to address persistent inflation. In the U.S. and abroad, returns have been historically and pitifully poor. Throughout the year, volatility—primarily emanating from rising interest rates—resulted in deeply negative returns among those bonds most sensitive to changes in interest rates (government bonds for example). But lower quality bonds (those rated below investment grade) have also woefully underperformed. This is why fixed income investors could have lost just as much money in Treasuries as they did in high-yield bonds.

There is nearly universal agreement on what it will take to stop the carnage—clarity on the end to central bank rate hikes. While the timing of this remains stubbornly uncertain, we do know what it will take for the Fed to change its tune. As Fed chair Jay Powell has made clear, “compelling evidence of inflation easing” is the precondition for a policy shift.

Meanwhile, the central bank is in a predicament. They know that monetary policy impacts the real economy with a lag. If we assume, for argument’s sake, that it takes six months for changes in interest rates to impact growth, then the very first Fed rate hikes from early 2022 are just starting to bite, with more pain to follow. This phenomenon of more pain is often referred to as “tighter financial conditions.” Simply stated, the Fed is trying to drive economic growth lower and take the pressure off inflation by reducing demand through higher interest rates—and this increases the cost of financing for consumers and corporations.

Have they been successful? The “good” news for the Fed is that they are seeing evidence that their policy is starting to work. There is some evidence that firms are currently not seeing the same price pressures as last year, but it has yet to make a material impact on headline inflation numbers. The risk is that the Fed goes too far with their interest rate hiking regime. Historically, financial conditions any tighter than what we have today, have been associated with recessions.

Individuals and institutions investing in the bond market also have a dilemma—what to do in their portfolios. We think there are two sets of positioning opportunities for investors:

1. Wait for the Fed to pivot: Investors looking to insulate themselves from interest rate risk could now benefit from much higher starting yields. A simple example are the yields on 1- to 5-year investment- grade bonds, which have increased to nearly 6% in 2022 from just under 1% a year ago. The price upside may be limited, but the current yield is quite attractive historically.

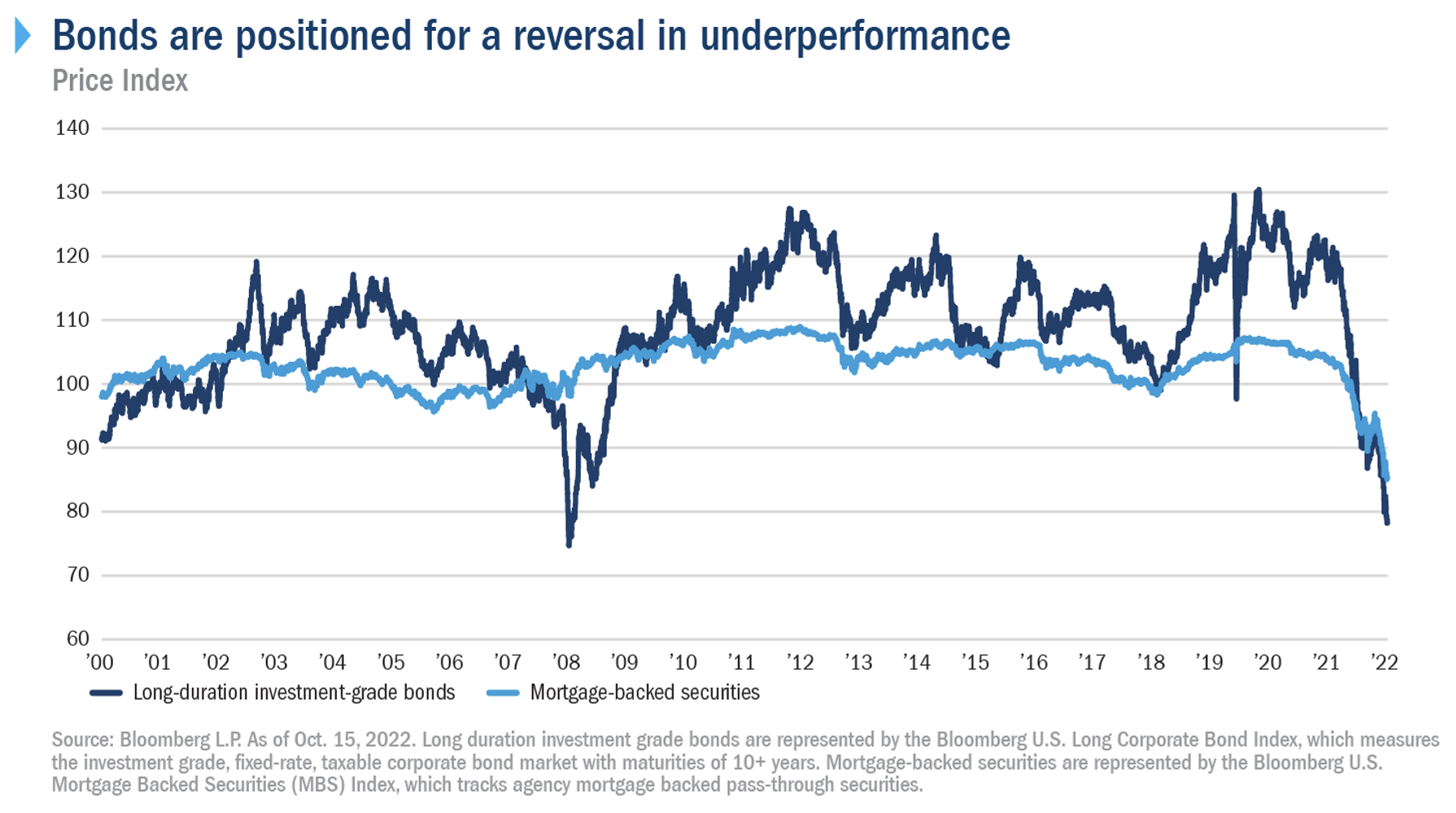

2. Position for a rebound now: Negative returns in the bond market are often followed by high, if not double-digit returns. Current average prices for high-quality bonds suggest the table is set for such a rebound. With government-guaranteed, mortgage-backed securities priced in the mid-$80s and long-maturity investment-grade bonds in the $70s, the combination of income and price appreciation can generate meaningful total returns once sentiment changes.

Which path you take is largely a function of how long you think the Fed will keep hiking. In either case, credit quality and careful credit selection will be key. The Fed is specifically trying to weaken the economy to reduce inflationary pressure. With that backdrop, investors should focus on issuers with the ability to withstand an economic slowdown. For that reason, we prefer high-quality issuers in the mortgage-backed, investment-grade, and municipal markets for this environment.

2022 has been brutal on bond investors, but ultimately the tide will turn. Whether investors choose to remain patient, or play for a rebound, the good news is that prices have changed dramatically, and both options look far superior when compared to sitting on the sidelines.

Gene Tannuzzo is global head of fixed income at Columbia Threadneedle Investments.