Setting Thresholds For Rebalancing Bands

While the concept is relatively straightforward, the question still arises, what exactly would the optimal threshold levels be for those tolerance bands? Investors must still apply a uniform rule, as they do with time-based rebalancing. Making the tolerance bands too wide or too narrow can also have deleterious effects.

For instance, should an investment or asset class only be rebalanced when its allocation moves more than 10 percentage points from its original target (e.g., an investment with a 50% allocation gets thresholds at 40% or 60%)? Or should it be set even wider, at 15%, to allow more room for favorable investment performance to be extended (and for a declining market to “finish” its decline)?

But absolute allocation bands become problematic in certain instances. If the portfolio is diversified across 10 different investment positions, each one has only a 10% allocation in the first place, so plus or minus 10% would be a range between 0% and 20%, which would require very extreme portfolio changes to ever trigger a trade (the investment would actually need to generate more than double the returns of its peers to generate a 10 percentage point overweight, or would have to crash to zero to be 10 percentage points underweight).

Of course, the target allocation bands could be made smaller for such portfolios—for example, an investor could set the targets at only 3%. Moving from 10% to 13% would still be a very big relative move—but it works well when all the positions in the portfolio have similar allocations.

For instance, if the portfolio is a “core-and-explore” approach with 50% in a core equity position, and a series of five satellites with 10% each, the 3 percentage point band would trigger the satellites to rebalance at 7% or 13%, but the core equity position will rebalance at 47% or 53% (which, given the relative size of the position, will be triggered far more often). Which means the satellites would have to outperform or underperform enough to change their weighting by 30% to be rebalanced, while the core would need far less relative under- or outperformance for a trade to occur.

An alternative approach is to simply scale the allocation bands relative to the size of the portfolio positions in the first place. For instance, rebalancing might occur anytime the investment’s weighting moves more than 20% from its original target weighting. So if the investment’s original allocation was 50%, and 20% of that is 10%, then the portfolio would be rebalanced when the investment’s weighting moves up to 60% (50% + 10%) or down to 40% (50% - 10%). On the other hand, if it was only a 10% allocation, the rebalancing trade would occur at thresholds that are 20% of the 10%, which means rebalancing would occur at 8% or 12%. Either way, the investment must effectively outperform all the others by approximately 20% on a relative basis to cause its relative weighting to drift above or below the thresholds (regardless of the weighting it started at).

That means any one particular investment moving to a high or low extreme will be sold or bought accordingly, because its performance is so different than everything else. The time-rebalanced portfolio, on the other hand, forces a rebalancing transaction for all investments in the portfolio, whether or not these investments need it. The new way allows you to “trim” an investment in the midst of a strong run, and purchase one that has just crashed (relative to the others).

Which Thresholds?

The key is to set the thresholds wide enough that they don’t trigger an excessive volume of trades (which rack up costs), don’t repeatedly curtail positive momentum, and don’t amplify a crash. At the same time, they must not be set so wide that no trades are triggered at all (the point of rebalancing would be lost).

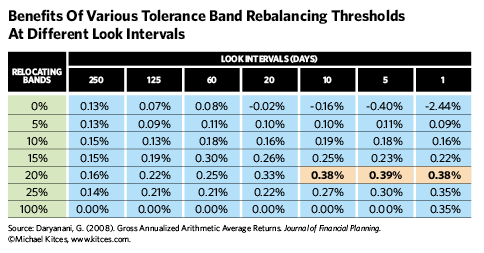

A 2007 study in the Journal of Financial Planning by Gobind Daryanani entitled “Opportunistic Rebalancing” studied rolling five-year periods from 1992 to 2004 and found that the optimal rebalancing threshold was at a relative threshold of 20% of the investment’s original weighting. Setting the thresholds narrower, at only 10% or 15% bands for example, produced less favorable results, as did setting the bands at 25%.

The goal, again, is to set a threshold that is “far enough out” to allow investments to run near extremes, but not so far that they run to extremes and bounce back again, without ever triggering a buy or sell trade.

The 20% relative rebalancing bands in the Daryanani study, which was based on a 60/40 portfolio (using five asset classes, including large-cap U.S. stocks, small-cap U.S. stocks, REITs, commodities and intermediate-term bonds), was sufficient to ensure that total equity exposure never drifted more than 5% from the original 60/40 allocation.

If fact, Daryanani ultimately found that this threshold-based rebalancing was so effective that the best strategy was to “look constantly” to see if there were any rebalancing opportunities (i.e., if the thresholds had been breached), even if it might be weeks, months or years without actually triggering a trade. Checking less often—particularly any less frequently than once every two weeks (every 10 trading days)—resulted in diminished rebalancing benefits. By looking often, investors can even increase overall returns, despite the fact that doing so curtails the long-term compounding of equities over time.

The Vanguard study also found that threshold rebalancing can slightly help returns, though it used narrow bands with a 5% absolute threshold (from a baseline 60/40 portfolio).

The caveat is that it’s necessary to do regular checks for rebalancing opportunities, which means using tools like iRebal, tRx (Total Rebalance Expert) or Tamarac (or perhaps a robo-advisor that employs a similar threshold-based rebalancing approach).

For those with the technological means, the tolerance threshold approach appears to be a more effective rebalancing strategy, both in terms of the timing and execution of trades.