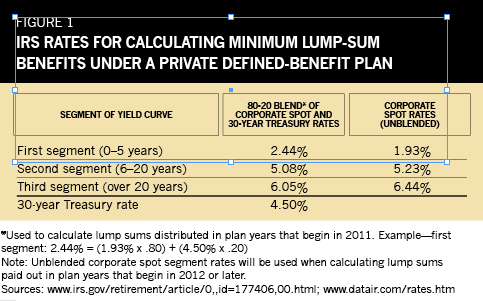

The accompanying chart looks at a recent month's rates. The two columns show the potential difference in discount rates come 2012. Under current conditions, the rate for the short-term segment would fall with the banishment of the long Treasury from the math, while the second and third segments' rates would rise.

How the Yield Curve Influences Payouts

For any particular participant, the net effect of the rule change hinges on age, along with such uncontrollable factors as the shape of the yield curve and the level of interest rates.

To illustrate, consider a 40-year-old worker whose plan is ending. His pension benefits are payable more than two decades hence. All of them therefore land in the third segment and its rate ought to be higher in 2012 when it becomes corporate-only, assuming no change in interest rates generally. A smaller payout results.

On the other hand, says Inglis, with a participant about to retire, the first five years' payments lie in the first segment. Its rate figures to be lower next year under the new rules, which would increase the present value of those benefits, again assuming not much change in interest rates overall. Payments falling in later segments, though, would have reduced present values.

"When the yield curve is steep like it is today, a younger participant will be much more negatively impacted by the new rules than an older one," Inglis concludes. If the yield curve were to invert-which might happen if runaway inflation ignites, as some fear-the relationship would flip.

Clients near retirement may wish to know how the change will affect their lump sum if they decide to work a little longer. Inglis says, "Advisors can point out that when interest rates are low, lump sums are more attractive relative to a period of high rates. But predicting interest rates is like predicting anything in the financial markets-not easy."

The new rule takes effect at the beginning of the 2012 plan year. Since sponsors usually know the rate for their new plan year in advance, "clients who are retiring close to the break in plan years should ask their sponsor for an estimate of the lump sum in both the current year and the next year," advises van Iwaarden. That will facilitate a direct comparison.

One Fat Check, or a Lifetime Income?

Deciding whether to take the pension or the lump sum hinges on many variables, according to David M. Hill, a financial advisor at Brinton Eaton, a wealth advisory firm in Madison, N.J. "There is no cookie-cutter solution. It's a client-by-client decision," he says.

In some cases, there frankly isn't much to think about. "We've unfortunately seen clients whose finances dictated taking a lump sum and taking the tax hit as well," says James Holtzman, an advisor and shareholder at Legend Financial Advisors Inc. in Pittsburgh. Participants who don't roll their lump sum to an individual retirement account or other tax-deferred vehicle owe tax on it.

When analysis is necessary, Hill starts by running lifetime cash-flow projections to determine whether the client's other assets and income sources will meet her needs. If not, the pension could be used to fill the budget gap, keeping in mind that it is fixed, and expenses may not be. When only part of the pension payment is needed, a partial annuitization of pension benefits may be the answer, if the plan allows it.