The past 15 or so years haven’t been kind to bond investors seeking income. For starters, coupon rates across much of the U.S. bond market dwindled significantly after the Federal Reserve slashed its target federal funds rate to near zero percent to help revive the economy following the financial crisis.

Then came the annus horribilis that was 2022, as the Fed began to aggressively raise its target rate to squelch rampant inflation. The target rate’s direction influences other interest rate movements, and when bond yields rise the price of existing bonds fall. That resulted in the worst year on record for U.S. bonds when the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index dropped 13%. That followed a year when the index fell 1.5%.

Conventional wisdom holds that bonds are a portfolio diversifier that supposedly zig when equities zag. However, in 2022 both stocks and bonds zagged. Or to be blunt, they both stank. Along with the bond market’s historic pratfall, the S&P 500 (excluding dividends) sank more than 19%.

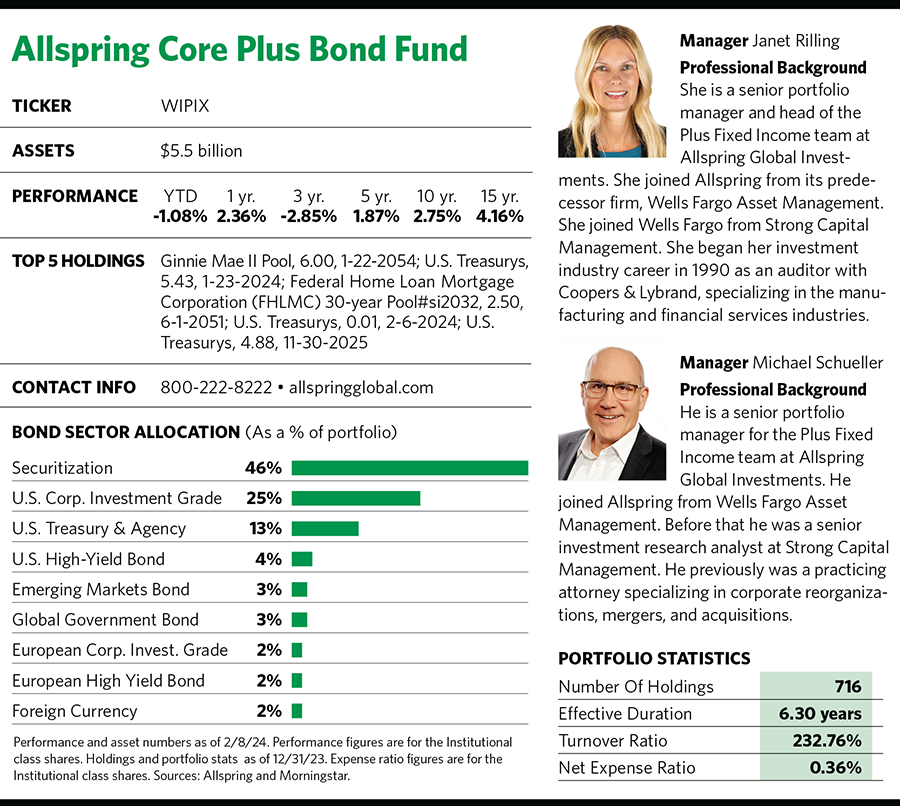

“We acknowledge that in 2022 there was a high correlation between asset classes, and fixed income was disappointing in that when equity markets sell off you look to fixed income as a ballast,” says Janet Rilling, a portfolio manager at the Allspring Core Plus Bond Fund since 2008. “But you have to look at what caused the selloff, and it was largely related to rates and the Fed hiking rates.”

That was then and this is now. After bond prices rallied strongly in last year’s fourth quarter, in large part thanks to a Fed policy pivot toward expected rate cuts in 2024, the fixed-income landscape looks more appealing in terms of current yields and, if rates do fall, potential price appreciation on existing bonds.

“When you look at where yields are today versus a historical basis, we think yields are attractive,” says Rilling, who heads the Plus Fixed Income team at Allspring Global Investments. She notes that the yield on the 10-year Treasury, which had dipped below 1% in 2020, recently exceeded 4%. “There is yield available, and that’s from the highest-quality part of the market. You layer in investment-grade credit and high yield, and those yields are even higher.”

Exploiting Inefficiencies

The Core Plus Bond Fund took its lumps in 2022 with a 13.7% loss. That was 42 basis points worse than its intermediate core-plus bond category tracked by Morningstar. Nonetheless, the fund has produced impressive long-term returns, including top-quartile average annual returns in its category in the five, 10 and 15-year periods, according to Morningstar. It also topped its category peer average and its Morningstar-designated benchmark in the one- and three-year periods (as of early February).

Core-plus fixed income is a total-return strategy that invests across the broader bond market. The Allspring fund’s benchmark is the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index, which tracks the investment-grade, U.S. dollar-denominated, fixed-rate taxable bond market.

According to Allspring, the core-plus bond category aims to improve on the yield and return of the benchmark with exposures to sectors, geographic markets and currencies beyond the core bond category. Allspring posits that the modest increase in volatility in core-plus portfolios has yielded attractive results, and that the Core Plus Bond Fund has handily topped its Agg benchmark in every measurable period since the fund’s 1998 inception.

As for yield, the fund’s institutional share class sported a 30-day SEC yield of 4.75% as of January 31. The SEC yield is used to compare bond funds and doesn’t exist at the index level. The SEC yield on the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF, which tracks the Bloomberg Agg and could be used as a proxy, was 4.2% in early February.

“Fixed-income markets in general have a lot of inefficiencies,” Rilling says. “This strategy has been designed to take advantage of that. The reason we like a core-plus strategy is that it has latitude to move from sector to sector.”

The fund can allocate up to 35% of its portfolio to what Allspring calls “plus” sectors such as high-yield debt, emerging markets debt, and non-U.S.-dollar corporate and government debt.

“We manage the portfolio as a foundational fixed-income allocation, and we’ll always have at least 65% in the investment-grade or the core part of the portfolio in those Agg sectors,” Rilling explains. “That gives us the return stream that’s correlated with the fixed-income market, and leaves us with 35% that we can allocate to the plus sectors.”

The fund has historically averaged about 15% in its plus sectors, but that number has varied from a low of 11% to as much as 30%. The fund recently had about 16% allocated to the plus category.

Of late, securitized assets have grabbed the attention of the fund’s five managers. As of last year’s fourth quarter they made up 46% of the portfolio, which was 17 percentage points more than the Agg’s allocation.

Securitized assets distribute risk by aggregating debt assets into a pool, then issue new interest-paying securities backed by the pool. They include the likes of agency mortgage-backed securities, asset-backed securities, collateralized loan obligations and commercial mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS—all of which play a role in the fund’s portfolio.

Rilling notes that the last of these, CMBS, has been in the eye of the storm, particularly when it comes to office properties. “We were neutral to underweight earlier last year, but we’ve been opportunistic on the margin adding exposure. We ended the year at between 2% and 3% in CMBS. We’re selective in what deals we add.”

As Michael Schueller, one of the fund’s co-managers, describes it, “We’re very focused on valuations, so we’re waiting for dislocations. When dislocations occur and valuations overreact to that we’ll move capital quickly to take advantage of those opportunities.”

Fire Hose Filter

The Allspring Core Plus Bond Fund recently held roughly 715 positions. That’s a lot, though it’s just a fraction of the number of constituents held by the Agg index. The portfolio’s size and market breadth mean that, when it comes to assessing investment opportunities, Allspring’s fixed-income analysts are like someone trying to drink from a fire hose.

“There’s a deluge of information coming at us every day,” Schueller says. “We’ve adopted a six-month approach in order to limit the sheer volume of data we need to consider.”

He’s referring to Allspring’s process of focusing its investment horizon on a rolling six-month time frame. The managers and the firm’s fixed-income analysts meet at year’s end and midyear to produce sector-level return forecasts for the next six months, taking into account factors such as monetary policy changes, the outlook for corporate fundamentals, the direction of rates, and predictions about whether credit spreads will widen or narrow.

Rilling describes her fund’s investment approach as a mix of quantitative and qualitative. “We’re always looking at relative valuations, so understanding valuations requires quantitative elements. We also do a lot of work at the sector level that looks at historic relationships between sectors.”

Among the quant tools they employ is the Black-Litterman model, an advanced asset allocation tool that lets Allspring’s analysts incorporate their qualitative views into the portfolio construction process.

“There’s always a judgment and an interpretation of the numbers that we use,” Rilling says.

Allspring’s fixed-income analyst team comprises nearly 50 individuals who do sector-level security research. That includes the portfolio managers. Rilling, for example, specializes in investment-grade credit, while Schueller’s forte is high-yield credit.

In between their six-month outlooks, the fund managers fine-tune their sector holdings and, if needed, adjust portfolio targets for bond duration, yield curve or other attributes. “As a group we’re very collaborative when we make a decision to change a target,” Rilling says.

Golden Moment?

One of Allspring’s mantras is what it calls riding the curve in fixed income. In other words, investors with cash on the sidelines shouldn’t wait for the all-clear signal—in the form of the Fed lowering interest rates—before adding duration to their fixed-income portfolios.

Duration is a measure of a debt instrument’s sensitivity to interest rate changes. Long-dated bonds have higher durations, meaning they’re more sensitive to rate changes because of their longer time horizons. When rates go up, the price of existing bonds generally go down. When rates go down, prices usually go up.

Some investors were burned last year on their long-term bond bets when they tried to front-run the Fed on rate cuts. Allspring calls for a measured approach that allocates across the yield curve in the current transitory period before the Fed starts cutting rates.

The company notes that yields have recently been at or near 15-year highs across the yield curve, and that longer-maturity yields are more in line with those on the front end of the curve. The firm believes this provides an attractive entry point for longer-duration exposures that could benefit if yields fall from these high levels.

Its research found that during the past four transitory periods in monetary policy dating back to the mid-1990s, investors with a diversified duration portfolio did much better than those who missed the opportunity by waiting for the golden moment to shift their duration positioning.

Because the Allspring Core Plus Bond Fund is meant to be a foundational fixed-income strategy for investors, its duration moves are limited to one-year long or short the Agg benchmark’s duration of about six years. Still, the portfolio managers shift durations up or down when appropriate and structure the portfolio to have duration exposure across the curve. In addition, the team runs a suite of strategies with varying duration profiles that an investor could use to ride the curve and position for different economic outcomes.

“We’re somewhat tactical about how we manage duration,” Rilling says. “We just don’t put a position on and hold it. We want to be sensitive to where rates are.”