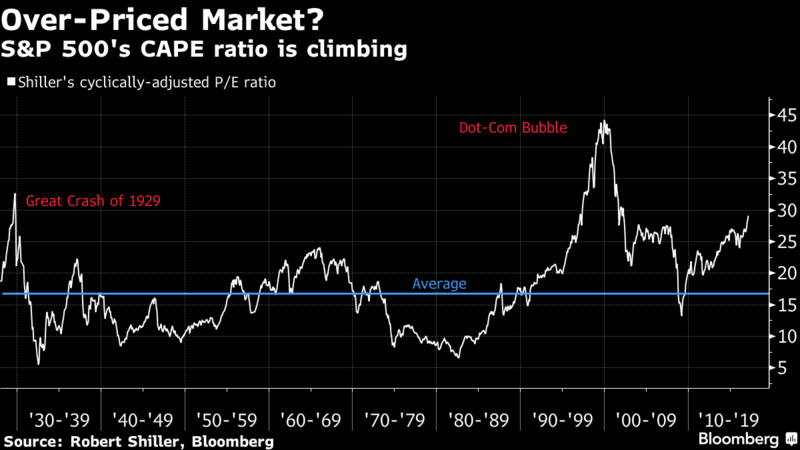

The last time Robert Shiller heard stock-market investors talk like this in 2000, it didn’t end well for the bulls.

Back then, the Nobel Prize-winning economist says, traders were captivated by a “new era story” of technological transformation: The Internet had re-defined American business and made traditional gauges of equity-market value obsolete. Today, the game changer everyone’s buzzing about is political: Donald Trump and his bold plans to slash regulations, cut taxes and turbocharge economic growth with a trillion-dollar infrastructure boom.

“They’re both revolutionary eras,” says Shiller, who’s famous for his warnings about the dot-com mania and housing-market excesses that led to the global financial crisis. “This time a ‘Great Leader’ has appeared. The idea is, everything is different.”

For Shiller, the power of a new-era narrative helps answer one of the most hotly debated questions on Wall Street as stocks set one high after another this year: Why are traders so fixated on the upsides of a Trump presidency when the downside risks seem just as big? For all his pro-business promises, the former reality TV star’s confrontational foreign policy and haphazard management style have bred uncertainty -- the one thing investors are supposed to hate most.

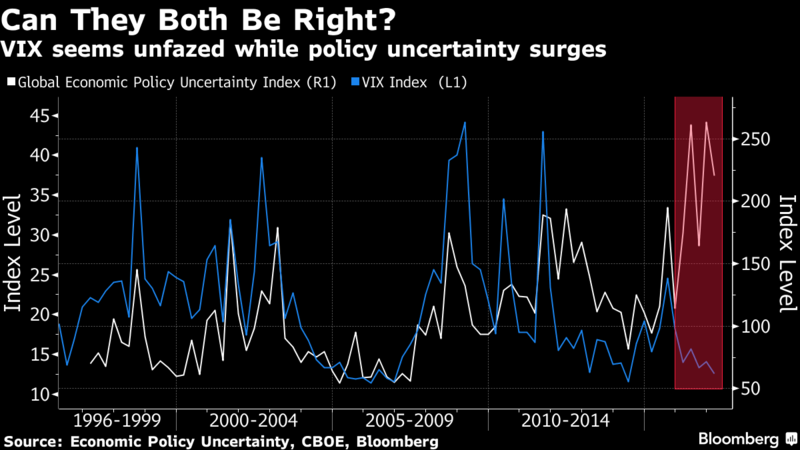

Charts illustrating the conundrum have been making the rounds on trading floors. One, called “the most worrying chart we know” by Societe Generale SA at the end of last year, shows a surging index of global economic policy uncertainty severing its historical link with credit spreads, which have declined in recent months along with other measures of investor fear. The VIX index, a popular gauge of anxiety in the U.S. stock market, has dropped more than 30 percent since Trump’s election.

“I don’t generally call the entire market wrong -- investors are very smart, highly motivated individuals -- but I find it hard to say why stock markets are so un-volatile right now,’’ says Nicholas Bloom, a Stanford University economist who co-designed the uncertainty gauge with colleagues from the University of Chicago and Northwestern University.

The simplest explanation may be that share prices have less to do with Trump than with tangible improvements in the economy and corporate earnings. With the U.S. unemployment rate well below 5 percent and S&P 500 Index profits projected to reach all-time highs this year, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that equities are doing so well.

But there’s more to the market’s resilience than just numbers, according to Ethan Harris, Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s global economist in New York. Like the fable of the boy who cried wolf, Harris says pessimistic forecasters have so badly over-estimated the consequences of big events -- the rolling European debt crisis since 2010, the U.S. debt-ceiling standoff in 2011, Brexit in 2016 -- that traders have become conditioned to ignore them. Even when bears are right, the past eight years have shown that central banks are more than willing to save the day when markets fall.

“It’s been a period of repeated shocks, and I think people get toughened against that,” Harris says. “It seems like uncertainty is the new norm, so you just learn to live with it.”

For Hersh Shefrin, a finance professor at Santa Clara University and author of a 2007 book on the role of psychology in markets, the rally is just another example of investors’ remarkable penchant for tunnel vision. Shefrin has a favorite analogy to illustrate his point: the great tulip-mania of 17th century Holland.