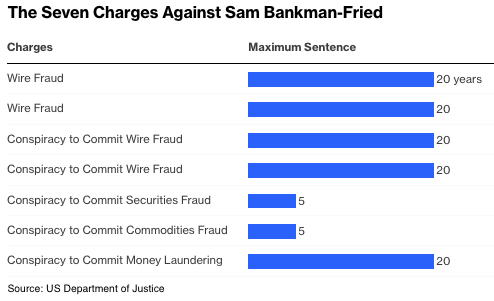

Justice has been served—and swiftly, too. A jury found fallen crypto mogul Sam Bankman-Fried guilty of seven counts of fraud and conspiracy after just five hours of deliberation, markedly less time than it took for jurors to puzzle over Elizabeth Holmes’ Theranos scandal or Raj Rajaratnam’s insider trading at hedge fund Galleon. And while this is certainly crypto’s biggest case of fraud, it undoubtedly won’t be the last.

If the 31-year-old’s culpability for the “pyramid of deceit” behind FTX’s collapse seemed so obvious, it’s partly because he was prosecutorial gold. You didn’t have to know what a blockchain was to comprehend his former lieutenants saying that the $8 billion of missing customer funds happened on his watch and with his knowledge. Nor did you have to grasp GAAP accounting to see that the frizzy-haired wunderkind’s own testimony contradicted his communications and electronic records. Bankman-Fried had no filter, though his lawyers might wish he had.

Having lost a lot of people a ton of money, Bankman-Fried’s lack of empathy and remorse played a big role in this trial. And that matters when committing corporate crimes: If you don’t care about other people, especially your customers, it becomes very easy to exploit them. Or, as Dan Davies put it on social media, to take a $10 billion account labeled “Not My Money” and re-label it “My Money.” There was a dangerous mindlessness to Bankman-Fried, once worth more than $15 billion, who openly played video games while giving interviews or holding meetings.

Bankman-Fried’s fate looks sealed, with lengthy jail time likely to be ordered when he’s sentenced in March, but I don’t believe for a second that this will be the last crypto fraud. We’ve closed one chapter of Covid-era laser-eyed true believers, yet market prices are stirring once more as TradFi firms see an opening to offer Bitcoin and other products with the potential blessing of regulators. FOMO remains strong. “One camp of people in my group is saying forget it, the value of crypto is zero, there’s nothing behind it,” Bjoern Jesch, the global chief investment officer of $900 billion German asset manager DWS Group, said in an interview with Bloomberg News. “And there’s this other group of people saying like, hmm, I mean at least there’s a price of $35,000 for Bitcoin. Someone is paying $35,000.”

There are other parts to the story of FTX that explain the incentives beyond the individual. The crypto sub-culture, for example, and its overlap with the aggressive quantitative trading culture where Bankman-Fried cut his teeth. Few in crypto-land seemed to blink an eye at the huge amounts of leverage offered by FTX, its lack of a chief financial officer or paucity of experience among its senior managers. The exchange’s raciest growth happened offshore while US regulators focused their attention on TradFi (where everything from public-transit tickets to expenses are scrutinized these days). FTX, along with other market players, even invented its own token, FTT, and used it as cash—Bankman-Fried’s view that “money is fungible anyway” is pure crypto babble, but plenty of people bought into it until the inevitable painful contact with reality.

You only have to read Going Infinite by Michael Lewis to see the cultural overlaps with his earlier book about 1980s Wall Street, Liar’s Poker. While at Jane Street, Bankman-Fried and those he would later hire took full advantage of a culture that encouraged teachable gambling between employees and interns—with a loss limit of $100 per day per intern—and put a rocket under it at Alameda Research and FTX, exploiting market inefficiencies but also settling scores. It may have been this score-settling that saw Bankman-Fried double down on misusing customer funds, for example when buying out rival platform Binance’s stake in FTX.

And then there’s the outer circle of willing enablers. What would Bankman-Fried have been without the long line of venture capitalists throwing more than $27 billion into crypto during 2021’s pandemic-fueled euphoria, clearly without serious due diligence? Or the institutional investors parking their funds at a trading venue in the Bahamas? Or the accounting firm based in the metaverse appointed to audit FTX? It’s easy to talk about “missed” red flags, but there was willful blindness here. In late 2021, I warned readers of the huge legal risk of sending funds to Binance and FTX, and in 2022 of the risk of a crypto exchange collapsing. When I asked one of my investing sources why, despite his own misgivings, he continued to use FTX, his answer was: “Because we can’t afford not to.”

There may be deeper reasons why the risk of fraud remains. In his 1993 book Out of Control, Zbigniew Brzezinski warned that a kind of self-indulgent and permissive attitude to capitalism would break people’s moral compass and simply outsource morality to the courts. He called it “procedural morality”—essentially, see what you can get away with until the law says “stop.” As clear as this week’s trial verdict is, that kind of incentive remains. With every boom-and-bust cycle, standards get lax and exchanges collapse. My own first exposure to crypto was reporting on the 2014 collapse of Mt Gox, helmed by a young geek called Mark Karpeles; he was cleared of embezzlement charges, and SBF’s antics in hindsight make his look positively minor. Even if banks take over more of the industry, I’m not sure the crypto culture around tokens backed by thin air pitched as digital gold will improve.

My other hunch is that FTX’s investment in hotly valued artificial intelligence startup Anthropic, which may play a big role in making some creditors whole, might have symbolic resonance down the line. In the coming years, the next big corporate scandal may very well have “AI” on its perpetrator’s resume. In the meantime, beware of gurus offering the future of money.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist writing about the future of money and the future of Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for Reuters and Forbes.