If you get beyond the political rhetoric [and assembled a group to solve Social Security] it would take them 15 minutes. It would take them 15 minutes only because 10 minutes was used for pleasantries.

—Alan Greenspan, Speech to the Commercial Finance Association on October 26, 2006

The federal government starts a new fiscal year every October 1. In a rational world, Congress would fulfill its responsibilities by passing bills before that date to authorize spending in the various agencies and programs. No one would be fully satisfied, but they would keep trying to push policy in their desired direction while recognizing life must go on.

We used to live in that world. Now it’s gone, replaced by gridlock and a series of short-term bills that only delay the hard choices. And voters seem okay with this, since they keep reelecting the politicians who produce it. (“Our congressman/congresswoman is not the problem. It's all those other guys!”)

This week the House passed two separate short-term extensions that will expire early next year. The next step will be either a government shutdown or another kick of the can down the road. There is, as we kids used to say, slim to no chance Congress will actually do its job, and Slim left town.

Worst of all, the annual discretionary spending bills are a relatively small dispute. The big money is in the vast entitlement programs whose expenditures are on unlimited autopilot, plus the interest we pay to finance them. We will never find the resolve to fix these much worse, and far more politically difficult problems, when we can’t even agree on next year’s budget.

All this should be exasperating no matter your political views. We deserve better. I can only keep preaching, hoping each time the message will get through to a few more people. I get glimmers of hope when people in high places thank me for saying it. At least they’re listening, even if they can’t do much.

Like many other programs, Social Security is unsustainable in its current form. And like many other programs, there are ways to fix it. We lack the will to actually do so. Today I’ll explain why.

Ignored Reality

The Social Security system was designed to look like a giant shared savings account. Workers and employers pay FICA taxes which go into a trust fund until the worker becomes eligible for benefits. Meanwhile they earn interest in a special type of Treasury bond.

In fact, it’s not “shared” at all. As with any other tax, the fact that you paid something into this system creates no legal obligation for the government to give you anything in return. That’s up to Congress, which can change its mind anytime. This was confirmed by the Supreme Court many years ago (Flemming v. Nestor, 1960).

Nonetheless, Washington maintains this façade because it’s politically useful and because the trust fund’s surplus (technically) lets them do so. Now the surplus is dwindling as a large generation of baby boomers lives much longer than the system’s designers envisioned. It will disappear completely around 2033, according to government projections. What happens then?

Under current law, if FICA tax revenue is insufficient to cover current benefits, then benefits will be cut by whatever amount is needed. The Congressional Budget Office calculates the cut would be about 25% in 2034, rising to 28% in 2053. That will be a problem for many people. Not me or probably you, who have investment or other income. But the vast majority of Social Security beneficiaries depend heavily on this income and don’t have many alternatives.

This presents a quandary. These cuts will happen unless Congress agrees on some way to close the difference between tax revenue and promised benefits. It’s not something they can delay with another “continuing resolution.”

For now, the answer is to just ignore reality. I don’t mean they just avoid talking about it. Congress is actively and intentionally obscuring the problem. Here’s how.

Remember last week I explained how the law requires the CBO to assume spending and revenue will continue as directed by current law, though of course we know the law will change. There are exceptions to that policy, one of which is Social Security. The CBO’s budget projections are legally required to assume that Social Security benefits will always be paid in full, whether sufficient funding is available or not.

This is called the “Scheduled Benefits” scenario. The CBO’s orders are to assume someone will magically solve the Social Security problem, without explaining where the money will come from. They could have told CBO to assume a magic hat with a rabbit in it. It would have been equally realistic.

This is actually a well-known phenomenon in economics. Economists like to create models for the future, and since the future is messy and chaotic, which doesn't model very well, they make assumptions which makes it easier to create the model. Of course, in doing so, they are assuming away the real world. The most obvious example of this is the “Rational Market Theory” which is mathematically solid, only because the Nobel laureates who designed this assumed away the real world. Just like Congress assumes that when push comes to shove somehow the Social Security problem will be solved.

Actually, I believe it will be. But the solution won't look like anything in anybody's projections or mine today.

Scheduled Insolvency

Perhaps realizing how ridiculous this is, the CBO also publishes a separate “Payable Benefits” scenario, which is limited to Social Security’s dedicated funding (i.e., the trust fund and projected payroll tax revenue). This also requires numerous assumptions, but they at least have some basis in reality.

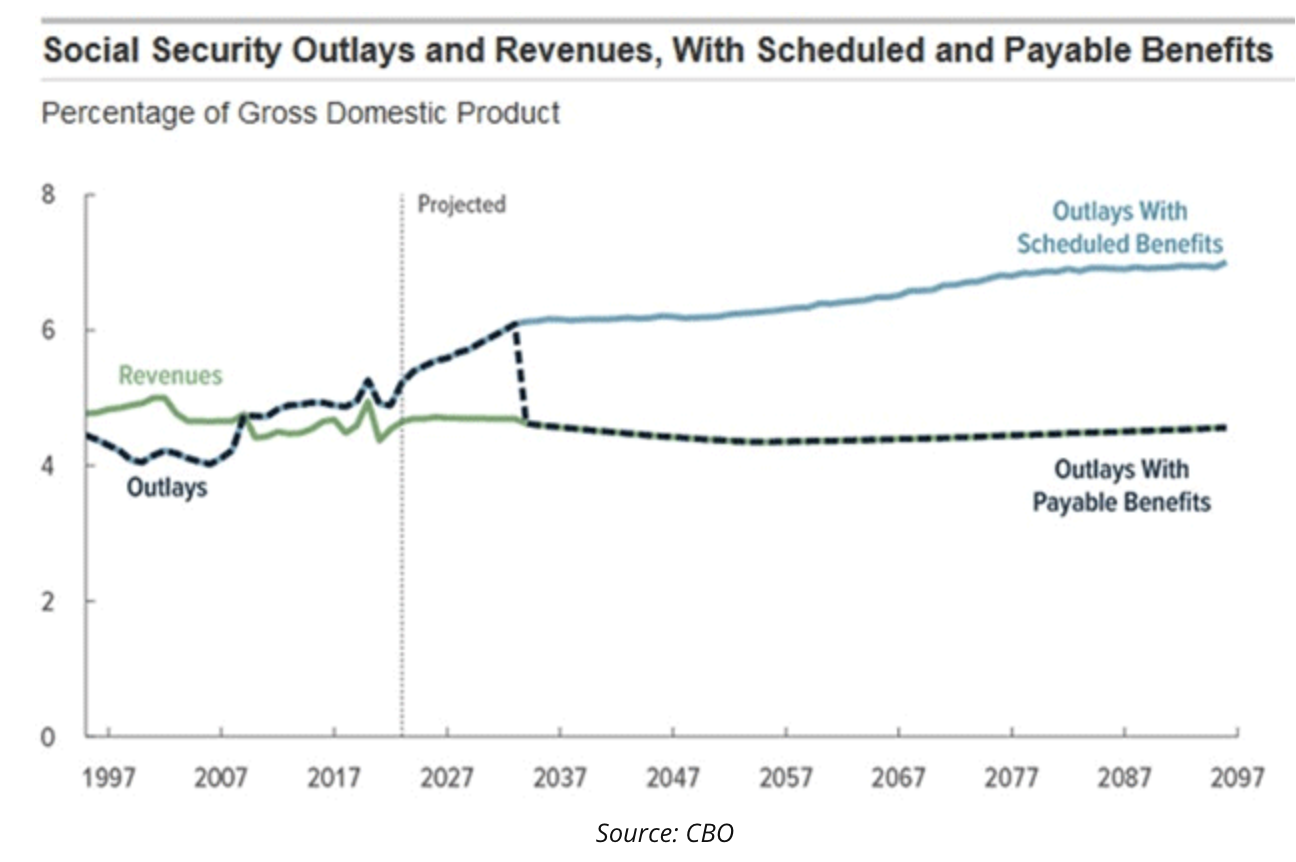

Here’s a chart comparing them. The blue “Scheduled Benefits” line is the magic hat scenario. It assumes the cash needed to pay everyone their promised amounts will simply appear from some unknown source. The black dashed line is the “Payable Benefits” scenario in which benefits are paid only from what’s available: the trust fund (for now) plus that year’s projected payroll tax revenue.

You can see in the little vertical line the point (estimated 2033) at which the trust fund is fully depleted, leaving the system fully dependent on current tax revenue. No one has any idea how that will go. Here’s how CBO describes it.

“If a trust fund was depleted and its expenditures continued to exceed its receipts, two federal laws would come into conflict. Under the Social Security Act, beneficiaries would remain legally entitled to full benefits. However, under the terms of the Antideficiency Act, the Social Security Administration would not have legal authority to pay those benefits on time. (That act prohibits government spending in excess of available funds.) It is unclear what specific actions the Social Security Administration would take if a trust fund was insolvent.”

Needless to say, this will be a mess. It’s hard to imagine Congress allowing any such thing to happen but avoiding it will require some combination of higher payroll taxes and reduced (or postponed by higher retirement age) benefits, which also won’t be easy. Waiting to act makes it even harder and more expensive. (They could also cut other parts of the budget to sustain Social Security, but that would forever disprove the notion Social Security is somehow independent.)

The CBO rather drily notes the Payable Benefits scenario would have some beneficial effects, though. The agency estimates that debt held by the public in 2053 would fall to 132% of GDP instead of 181%. Savings rates would go up, reducing interest rates and the Treasury’s borrowing cost. Many senior citizens would return to the job market and expand the labor supply, enhancing GDP growth.

That all sounds good but is not realistic. Retired people can vote and, in this situation, would likely do so in droves. Angrily so. Where that would lead is anyone’s guess. Probably nowhere good.

Third Rail

Let’s recap. Without big changes, in 2033 (+/- a couple of years) the Social Security “trust fund” will be gone. At that point it will become a “pay as you go” system without enough tax revenue to cover its obligations, which will force steep and immediate benefit cuts. This situation isn’t currently reflected in the official federal budget projections because Congress has ordered CBO to ignore it.

The last time we solved a Social Security crisis was in the early 1980s under Reagan and Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill. It was supposed to fix Social Security for all time, but of course it didn't.

George W. Bush actually ran on a platform to fix Social Security, which to his credit he realized was a serious problem. No one was surprised when Democrats were opposed, but Bush couldn't get Republicans close to the “third rail,” either. (The third rail is how electric trains get their power. Touch it and you die, or don’t get reelected.)

The longer Congress waits, the harsher the necessary changes will have to be. There is no sign anything will happen—certainly not before the 2024 elections—and the clock is ticking. Few in Congress are even talking about how to avoid this train wreck.

Yet one way or another, we will have to bite this bullet, and I mean “we” in the broadest sense. It affects everyone since retirement-age Americans are a large and growing percentage of the population. Social Security is a large part of their income. As it changes, your customers might not be able to spend as much as you thought, or your elderly parents might need more help than expected.

Probably the least painful step would be raising the retirement age. I say “least painful” instead of painless. Delaying eligibility means some people will get less over time. That’s the whole point of doing it. Each one-year increase reduces their lifetime benefits by around 5%, according to one estimate I saw.

Further, if biotechnology develops as I expect, life expectancy will keep rising, and particularly for the high earners who get the highest benefits. This will consume some (and maybe all) of the savings from raising the retirement age.

Telling people to work a few more years also assumes employers will want to continue paying them. As any 60+ person who has ever looked for a job will tell you, that’s not always the case. Age discrimination is a real problem. Conversely, keeping older people in the workforce longer might reduce opportunities for some younger people. The spillover effects could be significant.

What else can we do? The two primary targets are 1) the taxes people pay in their working years and 2) the formulas by which benefits are initially awarded, adjusted for inflation, and (sometimes) taxed. Let’s examine these in that order.

The Social Security tax is split between employees and employers, each of whom pays 6.2% of earnings up to a cap, which is $160,200 this year and will adjust upward to $168,600 next year. If you’re self-employed you pay the employer side as well, so it’s 12.4%. On the full amount, that is $20,900. (Plus Medicare taxes, plus income taxes, plus…)

Many workers pay more in Social Security (plus the separate Medicare tax) than their income tax liability. And, while you can reduce it a bit with benefit plans and such, this is a hard tax to avoid. Which means raising it would touch practically every worker and is thus politically difficult.

If Congress could somehow find the will, raising this tax might buy some time. One calculator I consulted estimates a one percentage point increase (split between employee and employer) would push that 2033 deadline out to 2040, even without changing anything else.

They could do roughly the same thing by raising the cap so that more wage income is taxed, which might be more politically palatable though economically destructive. But again, this would only delay the problem a few years instead of fixing it.

Congress could also change Social Security benefits in a variety of different ways. The current system determines your initial benefit amount by a formula based on replacing a certain percentage of your lifetime job earnings, and thereafter adjusts it for inflation each year. They could tweak these formulas to produce “savings” without overtly noticeable cuts.

Various kinds of “means testing” are a common reform idea. This would mean reducing or even eliminating benefits to retirees with other income sources. We actually already do this by making some benefits taxable over certain income levels. These people get their benefits then send a portion of it right back with their income tax return. It is “means testing” in all but name. They could do more of this.

This would, of course, make those people unhappy. Didn’t they pay their fair share into the system and now they get no benefits? Is Social Security just welfare then when not everyone gets it, even if you paid the highest amount over your lifetime?

Another common idea is to invest some of the Social Security trust fund in stocks or other private assets. While I am sometimes bullish and sometimes bearish on the short-term market returns, I am very bullish over the long term, say 30–40 years. Various experts have proposed different ways to include other investments in Social Security. This is worth pursuing but would be a long-term solution. The more immediate challenges would remain.

(Not to mention, you can’t invest the trust fund in stocks or anything else unless the trust fund has a surplus. As of now, the younger worker’s tax revenue is needed to pay current benefits. We’d have to solve that problem to make any of these plans feasible.)

As you can see, every option has limitations.

My opening quote from Greenspan is right. Social Security is an “easy” fix, compared to other programs. But it will mean compromise and touching the third rail. Anyone who proposes something mathematically rational will be accused of pushing grandma off the cliff (we actually had those ads in previous political cycles)!

When politics wins over rationality, when kicking the can down the road is the easier political choice, it means we won’t have a solution until there is a crisis, which is coming in less than a decade.

Right now, interest expense for the U.S. government is approaching the size of the U.S. defense budget. In 10 years? When the CBO projects almost $3 trillion deficits a year and total debt will be well over $60 trillion, the cost of interest will be approaching the Social Security expense. Their calculations, not mine. They have consistently underestimated the final number for the debt 10 years out, because by law they must assume both parties won’t find ways to spend more money.

You likely already knew Social Security was a problem. I hope this letter demonstrates it’s an even worse problem than you thought—and we haven’t even talked about Medicare yet.

Decades of promises are finally running into reality. Reality is going to win.

Social Security: Our Mistake, Your Responsibility!

Finally, speaking of Social Security, my friends Terry Savage (the well-known financial columnist) and Professor Larry Kotlikoff have a new book on Social Security called Social Security Horror Stories.

Social Security admits it has made $21.6 billion in incorrect benefits payments! Now it wants its money back—from widows, orphans, retired schoolteachers, and even young children whose parents received disability benefits on their behalf. Often with no explanation, they send threatening letters clawing back amounts ranging from several thousand dollars to more than $100,000. The claw back notices all carry the threat that benefits will be stopped immediately if a repayment plan is not set.

60 Minutes reported on these stories last Sunday. Anderson Cooper featured three families with egregious clawback problems. Their book and website have even more. The bureaucrats say they have no choice but to recover the money, but of course, when Anderson Cooper called, those debts suddenly went away. Apparently, they can make exceptions, but choose not to unless you can get Anderson Cooper to call.

One story was a young man whose family got disability benefits starting when he was 11 because he had cerebral palsy. Now, 20 years later, they want him to pay it back because even though he still has the condition, he is working.

The book is a stark reminder of how powerful bureaucracies can run amok, overwhelming those least able to deal with them. Lawyers don’t want to take up the cases and mostly those affected can’t afford lawyers.

Essentially, the attitude at Social Security is that it is our mistake but your responsibility to fix it. Perhaps we should privatize the bureaucracy, and as part of the contract, make the private company pay for its mistakes. With senior management paying part of that out of their own pockets. A little incentive to get things right.

Congress is now looking at this. We should thank Terry and Larry for making this egregious behavior known. Get the book if it interests you.

John Mauldin is the co-founder of Mauldin Economics.