Discussions about manufacturing tend to get very contentious. Many economists and commentators believe that there’s nothing inherently special about making things and that efforts to restore U.S. manufacturing to its former glory reek of industrial policy, protectionism, mercantilism and antiquated thinking.

But in their eagerness to guard against the return of these ideas, manufacturing’s detractors often overstate their case. Manufacturing is in bigger trouble than the conventional wisdom would have you believe.

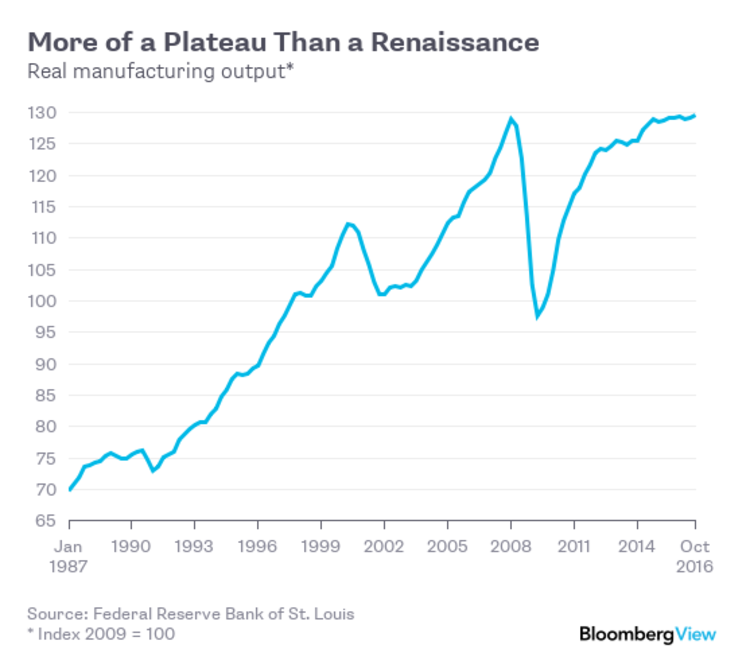

One common assertion is that while manufacturing jobs have declined, output has actually risen. But this piece of conventional wisdom is now outdated. U.S. manufacturing output is almost exactly the same as it was just before the financial crisis of 2008:

In the 1990s, it really was true that manufacturing production was booming even though employment in the sector was falling. During that decade, output rose by almost half. That’s almost a 4 percent annualized growth rate. The expansion of the early 2000s, in contrast, saw manufacturing increase by only about 15 percent peak-to-peak over eight years -- less than a 2 percent annual growth rate. And in the eight years between 2008 and 2016, the growth rate has averaged zero.

But even this may overstate U.S. manufacturing’s performance. An alternative measure, called industrial production, shows an outright decrease from a decade ago:

So it isn’t just manufacturing employment and the sector’s share of gross domestic product that are hurting in the U.S. It’s total output. The U.S. doesn’t really make more stuff than it used to.

What’s more, the overall numbers hide serious declines in most areas of manufacturing. A 2013 paper by Susan Houseman, Timothy Bartik and Timothy Sturgeon found that strong growth in computer-related manufacturing obscured a decline in almost all other areas. “In most of manufacturing,” they write, “real GDP growth has been weak or negative and productivity growth modest.”

And, more troubling, the U.S. is now losing computer manufacturing. Houseman et al. show that U.S. computer production began to fall during the Great Recession. In semiconductors, output has grown slightly, but has been far outpaced by most East Asian countries. Meanwhile, trade deficits in these areas have been climbing.

In other words, Asia is still solidifying its place as the workshop of the world, while the U.S. de-industrializes. The 1990s provided a brief respite from this trend, as new industries arose to replace the ones that had been lost. But the years since the turn of the century have reversed this short renaissance, and manufacturing is once more migrating overseas.

Manufacturing skeptics often draw parallels to what happened to agriculture in the Industrial Revolution. But the two situations aren’t analogous. In the 20th century, U.S. agricultural output soared even as it shed jobs and shrank as a percent of GDP. Machines replaced most human farmers, but the total value of U.S. crops kept climbing.