With the Federal Reserve poised to raise short-term interest rates to fight inflation, more than a few investors worry that higher rates will sink stocks. But there’s just as much reason to think the opposite will happen.

The endlessly repeated idea that interest rates and stock prices move in opposite directions is grounded more in theory than data. The theory is that stock prices reflect the present value of companies’ future earnings, dividends or cash flows, a calculation that requires an interest rate to “discount” future dollars to the present. The higher the interest rate, the less future money is worth today, and vice versa. Therefore, rates go up and stock prices go down.

Many U.S. investors are convinced that’s exactly what they witnessed repeatedly during the past two decades. It started, they say, when the Fed dropped interest rates in the early 2000s in response to the dot-com bust, lifting stocks in the ensuing years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. It happened again when the Fed dropped rates near zero in the aftermath of the financial crisis and kept it there for years, triggering one of the longest bull markets in history. And it happened a third time when the Fed lowered rates back near zero in response to the pandemic last spring, causing broad stock market averages to double in just more than a year.

Leaving aside that it’s hasty to draw conclusions from three anecdotes, two of which involved historic declines that gave stocks a lot of ground to reclaim, there are many reasons to be skeptical that interest rates move the market. For one, stock investors make decisions based on a variety of factors, many of which have little or nothing to do with interest rates or even companies’ future prospects, such as technical analysis, values-based considerations or just speculation. So the idea that stock prices merely or even mostly reflect the present value of companies’ future cash flows isn’t well grounded in reality.

That may explain why the longer history of interest rates and stock valuations doesn’t show any reliably inverse relationship. The correlation between 10-year Treasury yields and the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio for the U.S. stock market is only slightly negative (-0.21) over the past 140 years, meaning very weak negative correlation, if any. There have been many times when interest rates and stock valuations have been simultaneously above or below average, bucking the idea that interest rates necessarily push stocks in the opposite direction. (A correlation of 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the same direction, whereas a correlation of negative 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the opposite direction.)

There’s also the fact that interest rates are generally lower in other developed countries and have been for years. Yet low rates have failed to boost foreign stock markets, which haven’t moved much since the financial crisis, as every disappointed investor with a globally diversified stock portfolio can attest.

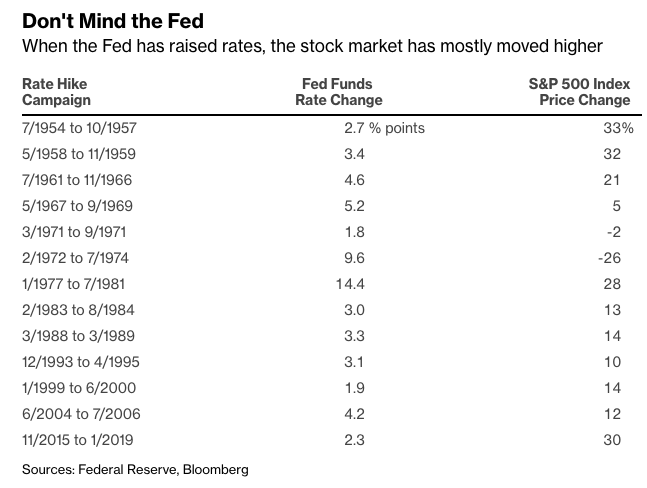

But perhaps the biggest reason for skepticism is that all three anecdotes since the dot-com crash involve interest rates going down and stocks going up. If rates and stocks do indeed move in opposite directions, it should work both ways, and it rarely has. By my count, the Fed has embarked on 13 rate-raising campaigns since 1954. Rather than sinking the market, the S&P 500 Index moved higher during 11 of them, with a median gain of 14%, excluding dividends.

The two exceptions were a brief rate hike campaign in 1971 in which the market declined 2%, and a longer one soon thereafter from 1972 to 1974 in which the market declined 26%. The latter episode coincided with an oil embargo that tipped the economy into a long recession, so it’s hard to know how much to blame rising interest rates for the selloff.

It makes sense that stocks have mostly moved higher during Fed rate increases. The Fed generally raises rates when the economy is doing well, which is also good for stocks. In fact, 11 of the Fed’s 13 rate hike campaigns coincided with a booming economy. The two outliers were during the 1970s and early 1980s when the Fed was forced to fight runaway inflation with higher rates despite a weak economy. In one of those cases, the stock market moved higher anyway, although not enough to offset higher inflation.