Last week I argued that the right focus for fiscal stimulus was to support businesses unable to operate during the pandemic in order to protect jobs. In several European countries, aid of that kind has so far amounted to around 10% of GDP. But as restrictions gradually ease, the need for fiscal support will diminish.

Attention should now turn to reallocating capital and labor. For over a decade, an extraordinary degree of monetary stimulus failed to generate growth in the industrialized economies. Excess capacity has built up in some sectors, creating a growing number of zombie companies. Overall, investment has been insufficient to absorb global savings. This “secular stagnation” did not respond to massive monetary and fiscal stimulus. What’s required instead is a reallocation of resources to eliminate excess capacity in sectors that expanded too much and to encourage investment in sectors with unexploited investment opportunities.

Even before the financial crisis, the pattern of demand and output in the world economy had become unsustainable. The price signals that might reallocate resources from unprofitable to profitable investments—interest rates and exchange rates, in particular—have been suppressed.

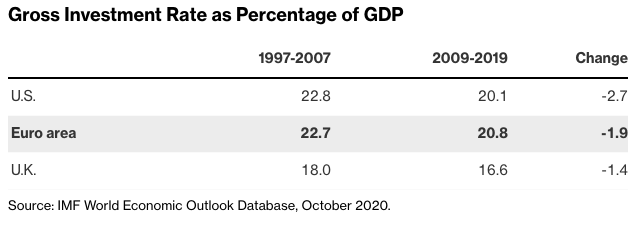

Low or even negative interest rates have permitted zombie companies to survive. And investment in the industrialized world has been weak. In the decade following the financial crisis, gross investment as a share of GDP fell by two percentage points in the G-7 economies. In China, the share of investment in GDP rose by over seven percentage points to an unsustainable 44.8%.

As the decoupling of the U.S. and Chinese economies proceeds—with China still needing to import high-quality semiconductors and the U.S. restricting the transfer of technology to Chinese companies—the underlying problem of excess saving in China and excess consumption in the U.S. remains. The share of household consumption in GDP in China fell from over 65% in 1952 to below 39% in 2019. Wages have been deliberately held down to keep exports competitive.

Escaping from a low-growth trap isn’t the same as climbing out of a Keynesian downturn. It requires different remedies—in particular, moving resources from one component of demand to another, from one sector to another, and from one firm to another. All this was true before the arrival of Covid-19, but the pandemic has underlined the point in two ways.

First, businesses and governments alike have come to realize that resilience is just as important as efficiency. Survival matters. We learned that lesson in respect of the banking system during the financial crisis, but we didn’t apply it elsewhere. Resilience of health-care systems, the risks posed by just-in-time delivery systems, and the susceptibility of economies to border closures all suggest that economic activity will be organized differently in future.

Second, the pattern of demand for a number of services, ranging from air travel to hospitality and entertainment, will change in ways that are impossible to quantify today. There will be a period of trial and error before we settle on a new pattern of spending and output.

The U.K., for instance, saw an extraordinary divergence last year between online retailing (sales up by almost half compared with 2019) and sales from clothing and other stores, which fell at record rates. Amazon didn’t need fiscal support. Retailers forced to close their shops, and restaurants and entertainment venues forced to close their doors, did. How far previous patterns of spending will return is unclear. No doubt shuttered restaurants and theaters will reopen to a wave of pent-up demand. But many changes in the pattern of spending are likely to persist and will require a reallocation of labor and capital.

Bringing about such a shift will call for a much broader set of policies than simply stimulating aggregate demand. The answer goes well beyond monetary and fiscal policies and extends to exchange rates, supply-side reforms and measures to correct unsustainably high or unsustainably low national saving rates. Let’s focus debate on how we might raise investment and speed this necessary reallocation.

Politicians are optimists. Central bankers are not. They know that every silver lining has a cloud. As the recovery proceeds, those who think monetary and fiscal stimulus will restore a healthy world economy are heading for disappointment. Conventional macroeconomic policy cannot correct a structural misallocation. More wide-ranging and ambitious policies are required that will be complex and difficult to implement. You might say we need the audacity of pessimism.

Mervyn King was governor of the Bank of England from 2003 to 2013. He is the Alan Greenspan Professor of Economics at NYU Stern School of Business and professor of law at NYU School of Law, and author (with John Kay) of Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers.