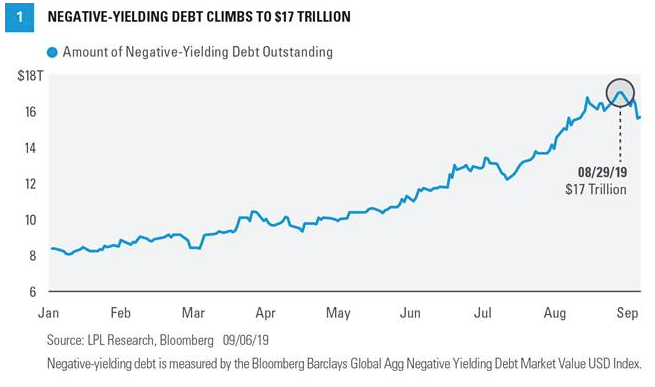

There’s a growing pile of negative-yielding debt around the world amid extraordinary monetary policy initiatives. While maintaining respect for global money flows, we believe the combination of economic fundamentals, domestic monetary policy, and a widening federal budget deficit limit the prospects for sub-zero yields in the United States.

Fixed income investing has traditionally been regarded as a stable source of yield for suitable investors.

One party lends another party money, and the lender receives interest in return for the risk incurred by providing capital.

Given extraordinary global monetary policy initiatives, however, that basic premise of fixed income investing has been turned upside down. There’s a growing pile of bonds around the world offering negative yields, in which a lender now pays the borrower for the privilege of loaning the borrower money.

Unfortunately, the global search for yield has now morphed into a scenario in which fixed income investors, or lenders, attempt to “potentially lose less” rather than “earn slightly more” than the value of the loan extended. Negative yields have also been a challenge for banks and savers, who both depend on rates for income. Wall Street has pointed to a flurry of theories why negative yields exist this late in the economic recovery—a global savings glut, aging populations, or a world bent on instant gratification (income today over income tomorrow). At any rate, negative-yielding debt is rapidly becoming the new normal.

The New Normal

Over the past several years, multiple central banks, including the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank (ECB), have enacted negative policy rates in order to boost economic activity and stoke inflation. Recently, central banks have loosened policy even more as the U.S.-China trade dispute curbs global economic activity and weighs on currencies. On September 12, the ECB cut its deposit rate for the first time since 2012, pushing it further into negative territory.

The trend of negative yields, led by global trade concerns, has yet to spread to the United States, but it has already pushed U.S. Treasury yields near all-time lows. While domestic economic fundamentals support a 10-year yield much higher than these levels, ultra-low rates elsewhere have spurred a global rush into Treasuries.

Fortunately, there are several catalysts that could at least keep a floor under U.S. yields. Domestic economic data remains healthy, and there are signs that global economic output has firmed in recent weeks. The S&P 500 Index has found its way back to within 2% of all-time highs, reducing the thirst for safe-haven assets. The ballooning federal budget deficit also may require more Treasury issuance, which could in turn increase the possibility of higher yields.