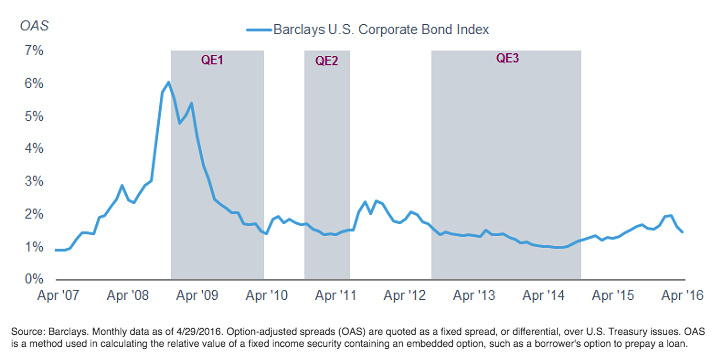

The Federal Reserve (Fed)'s quantitative easing programs only included Treasuries, agencies and agency mortgage-backed securities, not corporate bonds. But they still helped drive corporate financing costs lower. At the tail end of the Fed's last iteration of QE, yield spreads—the amount of yield a corporate bond offers above a Treasury with a comparable maturity—hit their post-crisis low a few months before the purchases were complete, narrowing from 1.7% to below 1% in July 2014.

Credit spreads generally declined during the Fed's QE programs

Source: Barclays. Monthly data as of 4/29/2016. Option-adjusted spreads (OAS) are quoted as a fixed spread, or differential, over U.S. Treasury issues. OAS is a method used in calculating the relative value of a fixed income security containing an embedded option, such as a borrower's option to prepay a loan.

While we still see some risks with investment-grade corporates—one example is the increase in corporate debt over the past few years to fund stock buybacks and dividends, rather than issuing debt to actually grow a business—demand should help keep the market supported.

Unintended consequences

It's worth noting that unconventional monetary policy can have unintended consequences, and the ECB is heading toward uncharted territory. While any fallout likely would affect the ECB and European corporate bond issuers rather than U.S. corporate bond investors, a few elements of the ECB's plan may prove challenging.

One concern is that corporate bond purchases by the ECB may lead to implicit subsidies for certain corporations. Although there are guidelines as to what the ECB can and cannot buy, ultimately the bank has to decide which bonds to actually purchase. For example, assume there are two European automakers that have bonds that fit the ECB's criteria for eligibility. If the ECB buys the bonds of one issuer and not the other, that issuer's funding costs may decline relative to its competitor, helping its bottom line. Is it up to the ECB to decide who deserves lower funding costs?

Also, bonds with ratings on the bottom rung of the investment grade spectrum—those rated BBB—carry increased credit risk. What happens if the ECB purchases a BBB-rated corporate bond, only to see that issue get downgraded to sub-investment grade?2 The ECB, on its website, addressed this concern by pointing out that it has minimum credit ratings for eligibility and due diligence procedures when deciding which issues to purchase. That should help mitigate the risk, but it won't necessarily prevent the ECB from buying a bond that turns sour.

What to do now

Think of yields in relative terms: Although U.S. corporate bond yields are near historic lows, they are some of the highest of all the developed economies. The ECB's corporate bond-buying program, by pressuring European corporate bond yields even lower, could potentially drive investors toward the U.S. investment-grade corporate bond market, leading to rising prices for domestic corporate bonds. We think this may enhance the value of your existing bonds, but could make it more expensive to add U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds to your portfolio.

Collin Martin, CFA, is director of fixed income at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

The ECB’s Latest Plan: What Does It Mean For U.S. Corporate Bonds?

May 9, 2016

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment