In Congressional testimony on March 2, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said that “it is more likely than not” that the central bank “can achieve what we call a soft landing” in the economy. In other words, he believes that the Fed can raise interest rates enough to get raging inflation under control without forcing the economy into a recession. The odds that Powell can pull that off are getting longer by the day.

History shows that when the central bank increases rates, a recession is almost assured. The Fed’s 12 rate-raising campaigns since the early 1950s resulted in 11 recessions, with the only exception coming in the early 1990s. What makes the Fed’s job extra hard now is that the inflation rate is so high. “To the extent that inflation comes in higher or is more persistently high than that, we would be prepared to move more aggressively by raising the federal funds rate by more than 25 basis points at a meeting or meetings,” Powell told lawmakers.

Increasing the odds of a recession this time is the Fed’s plan to reduce the almost $9 trillion of assets on its balance sheet after it stops buying U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities this month. Those assets have risen $4.8 trillion since the pandemic commenced in early 2020. Powell said the reduction will be conducted “in a predictable manner,” largely through letting obligations it owns mature rather than outright sales. Nevertheless, this is a big reversal from the $140 billion in asset purchases it had been making each month to support the economy through the pandemic.

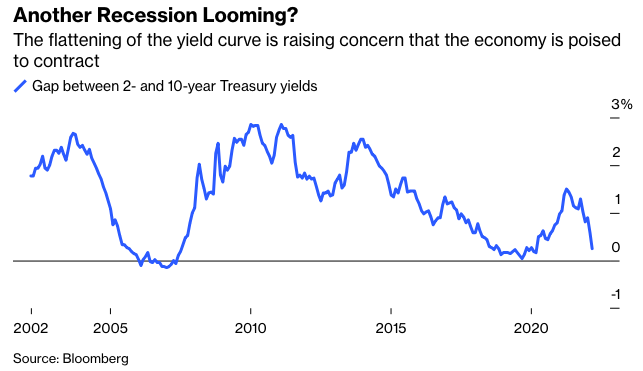

Another sure sign of a recession is an inversion of the so-called yield curve, which happens when the interest rate on the 2-year Treasury note rises above that on the 10-year note. An inversion makes it unprofitable for banks and other financial institutions that borrow through deposits and other short-term markets while lending at longer maturities. That restrains lending and thereby depresses business activity. At present, the 2-year yield is 1.53%, still lower than 1.84% 10-year note yield, but the spread has narrowed from 1.07 percentage points on Dec. 31 to just spx0.27 point.

The Fed is between a rock and a hard place. If it backs off tightening monetary policy, it risks persistent inflation, spurring buyers of goods to expect more of the same, so they buy ahead of need. The result is pressure on inventories and production capacity, leading to further price hikes. That confirms expectations and induces more pre-buying, generating a self-feeding inflationary spiral. Such was the case in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Major stock indexes are down anywhere from 8% to 15% this year. In recessions following significant credit restraint and yield curve inversions, the average drop in the S&P 500 Index has been 36% in recent decades. A similar plunge or greater is likely, given the extremely high level of equity prices as well as rampant speculation. It would take a 55% drop in the S&P 500 from here to bring the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio back to 17, which is its average over the very long term. And bear markets usually overshoot on the downside just as bull markets tend to exceed rational extremes. That’s especially true when the previous bull market was saturated with speculation—just like the latest one.

Robinhood Markets Inc., the darling of aggressive but green investors, plunged in the last half of 2021, and another 12% in January after reporting a $423 million loss in the fourth quarter. Bitcoin continues to be very volatile along with the overall stock market, typical of the opening stages of major bear markets. SPACs, with no sales or earnings and only the hope of merging with viable companies, are reminiscent of the dot-com companies of the late 1990s, which was followed by a Nasdaq plunge of 78%. Almost half of all startups with less than $10 million in annual revenue that went public last year through SPACs have failed or are expected to fall short of the 2021 revenue and earnings targets they provided to investors, according to a survey by The Wall Street Journal.

In this environment, investors should be extremely cautious. Stocks are still overpriced and vulnerable. Bond investors are worried about inflation. We may be entering a time when cash is king.

Gary Shilling is president of A. Gary Shilling & Co., a New Jersey consultancy, a registered investment advisor and author of The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation. Some portfolios he manages invest in currencies and commodities.