The Federal Reserve has hit the road this year in a nationwide “Fed Listens” tour. According to the central bank, this is an effort to conduct a broad review “of the strategy, tools and communication practices it uses to pursue the monetary policy goals established by the Congress: maximum employment and price stability.”

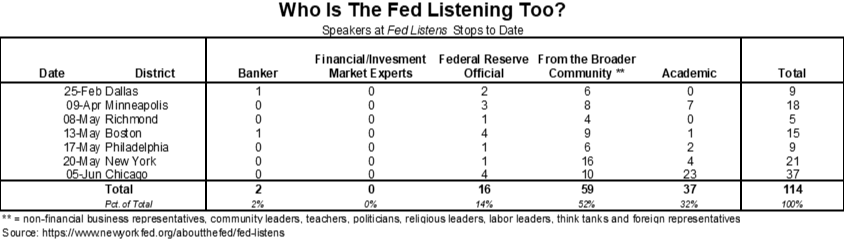

But is the Fed really listening? It is, just not to the markets. Of the 114 people the Fed invited to the six meetings to date, only two were bankers and none were financial market experts. Even the opinions of several politicians on the Fed’s dual mandate to seek full employment and stable prices were sought. The Fed has six more meetings scheduled, including a two-day conference in Chicago starting Tuesday that is being billed as the most important one of them all.

Although the tour is the Fed’s attempt to reconnect and listen to the opinion of outsiders at a time when there is growing concern that the markets and economy are not responding to monetary policy like they should, the absence of investors who could provide valuable insights is curious. It’s no wonder that many say the Fed has lost its “feel” for the markets.

Perhaps the lack of market participants is related to an incident in 2012, when Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond President confirmed non-public information about Fed policy deliberations to an analyst from newsletter publisher Medley Global Advisors. (Lacker resigned from the Fed in 2017 after admitting his role in the episode.) The Fed subsequently put in place severe restrictions on any communication between Fed officials and market participants, essentially walling off the central bank from a vital source of information and losing a “feel” for the markets.

Even though market participants haven’t had a major presence at these meetings, their opinion can be seen in the bond market’s yield curve and federal funds futures. Yield curves that include a policy rate, or those that include the federal funds or three-month Treasury bill rates, are higher than longer-term Treasury notes. This is a signal that monetary policy is too tight.

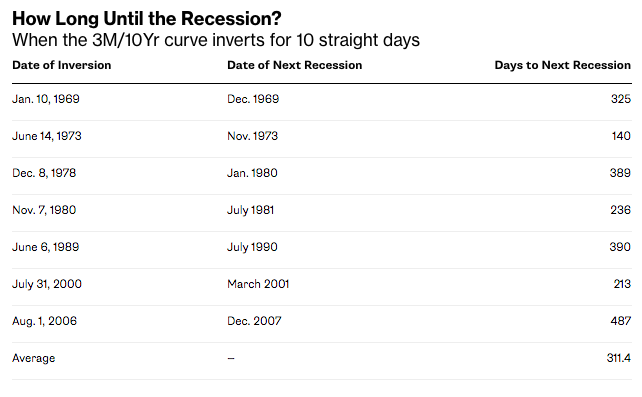

Whenever three-month bill rates rise above 10-year note yields for 10 consecutive days, a recession follows in 311 days. We are now at seven consecutive days that this curve has been inverted. (Ten consecutive days is a good marker because it suggests an inversion isn’t just a fleeting development.)

The fed funds market is offering another sign that monetary policy is too restrictive. The odds of an interest-rate cut at the Fed’s July meeting are 60 percent and 87 percent for the September meeting, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Additionally, the market is pricing in three rate cuts over the next year. And yet, the Fed’s latest “dot plot” shows some policy makers still view the need for more rate increases this year. In other words, the divergence between markets and the Fed means the potential is very high for a negative reaction in markets if the Fed doesn’t ease monetary policy by reducing rates soon.

And as noted in my Bloomberg Opinion column on May 21, markets are also diverging from the Fed on inflation. Market measures of expected inflation are pointing to rates of inflation remaining low for some time, a situation that Fed Chair Jerome Powell has called “transitory.”