Markets have been whipsawed in recent weeks, first by talk that a cooling labor market would allow the Federal Reserve to “pivot” away from its aggressive interest-rate hiking campaign, and then by comments from central bankers that any such move would be premature—as Thursday’s hot consumer price index report proved. Perhaps there’s a solution that would allow the Fed to continue to battle inflation while also addressing what is rapidly becoming a potential crisis in the world’s most important market—U.S. Treasuries.

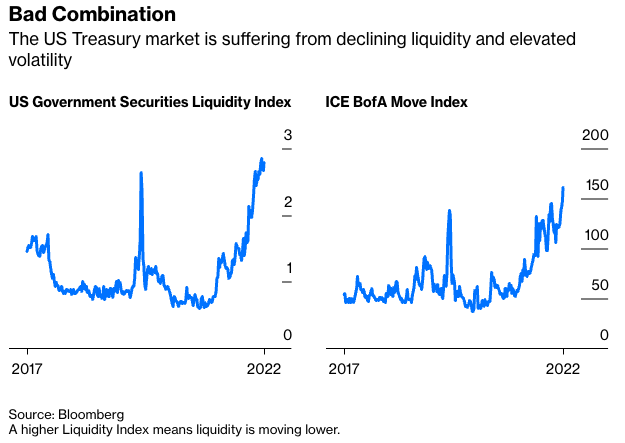

The word “crisis” is not hyperbole. Liquidity is quickly evaporating. Volatility is soaring. Once unthinkable, even demand at the government’s debt auctions is becoming a concern. Conditions are so worrisome that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen took the unusual step Wednesday of expressing concern about a potential breakdown in trading, saying after a speech in Washington that her department is “worried about a loss of adequate liquidity” in the $23.7 trillion market for U.S. government securities. Make no mistake, if the Treasury market seizes up, the global economy and financial system will have much bigger problems than elevated inflation.

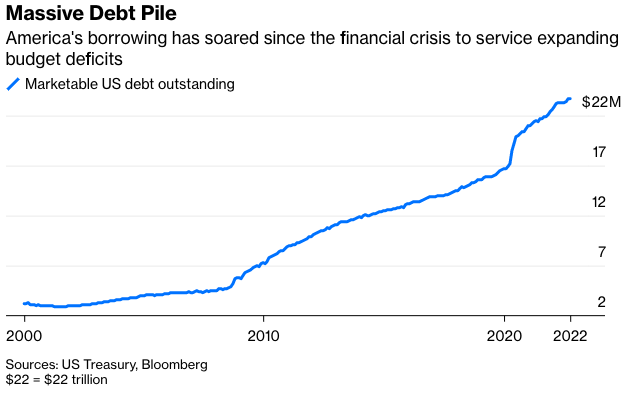

But rather than slow, or even stop, the pace of rate increases, which would only resurrect the notion that there’s indeed a Fed “put” designed to bail out investors, the central bank could choose to slow quantitative tightening. Whereas quantitative easing, or QE, injects liquidity into the financial system through bond purchases, QT has the opposite effect. Instead of selling bonds, the Fed is allowing the $9 trillion or so of U.S. Treasuries and mortgage securities it has accumulated on its balance sheet since the 2008 financial crisis to mature without replacing them. The amount of QT conducted by the Fed ramped up to the maximum of $95 billion per month in September from $47.4 billion.

The thing is, just like there’s no strong evidence that many years of QE had the desired effect of sparking inflation, it’s unlikely that QT will help temper inflation. What it is more likely to do—and is probably already doing—is cause havoc in the government bond market, the benchmark for all other markets that determine the cost of money for governments, companies and consumers.

A Bloomberg index shows liquidity in the Treasury market is worse now than during the early days of the pandemic and the lockdowns, when no one knew what to expect. Similarly, implied volatility as measured by the ICE BofA MOVE Index is near its highest since 2009. And in an unusual development that shows just how dysfunctional the Treasury market has become, the newest, most liquid securities, known as on-the-run notes, trade at a discount to older, tougher-to-trade off-the-run securities, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Daily swings in interest-rate swaps have become extreme, proving further evidence of disappearing liquidity.

What should be most concerning to the Fed and the Treasury Department is deteriorating demand at U.S. debt auctions. A key measure called the bid-to-cover ratio at the government’s offering Wednesday of $32 billion in benchmark 10-year notes was more than one standard deviation below the average for the last year, according to Bloomberg News. Demand from indirect bidders, generally seen as a proxy for foreign demand, was the lowest since March 2021, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Although the Treasury is in no jeopardy of suffering a “failed auction,” lower demand means the government is paying more to borrow.

All this is coming as Bloomberg News reports that the biggest, most powerful buyers of Treasuries—from Japanese pensions and life insurers to foreign governments and U.S. commercial banks—are all pulling back at the same time. “We need to find a new marginal buyer of Treasuries as central banks and banks overall are exiting stage left,” Glen Capelo, who spent more than three decades on Wall Street bond-trading desks and is now a managing director at Mischler Financial, told Bloomberg News.